Philippine Jails are a Covid-19 Time Bomb

The Philippines has the most crowded correctional system in the world. It’s only a matter of time before the virus enters and spreads in prison and jail facilities. Humanitarian groups have called for the early release of elderly and sickly and nonviolent, low-risk detainees.

BY AIE BALAGTAS SEE/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

ON APRIL 1, the police brought to a jampacked detention center at the Quezon City Police District headquarters 21 residents of a poor community who had been arrested for breaking quarantine rules.

When they got there, the detainees were not tested for the coronavirus nor were they isolated from other inmates. “The police just took their body temperature using a thermal scanner and that was it,” said lawyer Kristina Conti, who represented them.

Since none of them showed Covid-19 symptoms, said Conti, they were locked up without being required to undergo a 14-day quarantine.

Because the detention cells were already full, the 16 men were kept outside a 5×5 meter cell for male detainees that already housed nearly a dozen other inmates. Later they were moved to another cell, all of them crammed in a 3×4-meter space. The women were placed with other female detainees in a separate cell.

“Social distancing, of course, is impossible,” Conti said. At night, the inmates slept side-by-side on the same cold floor. They didn’t have easy access to toilets, making frequent handwashing difficult. The jail did not provide rubbing alcohol, masks or soap, although some donors sent some supplies.

Police lockups like those at the Quezon City police headquarters in Diliman are temporary holding areas for suspects undergoing investigation or awaiting court orders that would send them to more permanent detention centers.

On March 14, just before the Metro Manila lockdown, the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) suspended the transfer of these suspects to the 467 district, city and municipal jails under its jurisdiction.

This means that suspected offenders will have to be kept indefinitely in small lockups in police precincts that do not have clinics nor doctors and nurses on staff. Most of these also do not have enough toilets or showers to service the influx of new inmates.

As of last week, more than 20,000 had been arrested for quarantine and curfew violations. Most have been released and will face charges once the health crisis is over. Some 4,000 are currently being detained in police lockups and are awaiting transfer to city jails.

“If the police continue to arrest, their detainee population will continue to grow and will make their situation worse,” said Raymund Narag, an associate professor at Southern Illinois University and an expert in Philippine jails. “Our police detention centers are extremely congested and do not have the capacity to segregate, much more isolate, infected individuals.”

File photograph: Rick Rocamora. This image appeared in Rocamora’s 2018 photobook Human Wrongs, a six-year project that documented life inside Philippine detention centers.

Health risks of overcrowded jails

Narag was once a prisoner himself, having spent six years at the Quezon City Jail before he was found innocent of involvement in a fraternity rumble that resulted in the death of one student.

“The Philippines has the most crowded correctional system in the world,” he said. “It is only a matter of time before infections creep into the very congested jail and prison facilities.”

Like other prison advocates around the world, Narag is calling for the release of nonviolent, low-risk, and bailable pretrial detainees as well as vulnerable, elderly, and sickly convicts.

Both the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Human Rights Watch have also asked the government to release nonviolent prisoners, saying overpopulated prisons, jails and lock-up cells make them fertile grounds for spreading infectious diseases.

“The early release of the most vulnerable detainees (elderly, sick) and those with minor offenses is an option that could be taken by the Philippine government,” said ICRC spokesperson Allison Lopez.

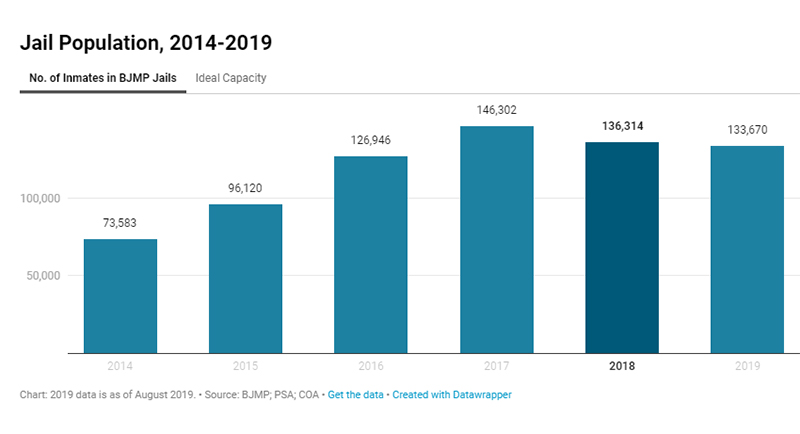

According to the BJMP, jails across the country are running at 500% overcapacity. In March this year, these jails had 134,748 detainees nationwide, a 40% increase since 2015, largely because of the surge of detainees from the government’s anti-drug campaign.

Even before the pandemic, poor jail conditions have already resulted in the death of 300 to 800 inmates annually in recent years, according to BJMP doctor Paul Borlongan. In 2018 alone, 40 prisoners died each month in different BJMP jails in Metro Manila, said Narag.

The 21 residents who were arrested on April 1 came from Sitio San Roque in Quezon City’s Barangay Bagong Pag-asa, which has six recorded Covid-19 cases. Earlier that day, the residents had gathered near the Trinoma mall along North EDSA to demand government aid because they were hungry.

After five days in detention, all 21 were released on bail on Monday afternoon. They returned to their shanties in Sitio San Roque, where some 6,000 families live in crowded settlement of tiny, wooden and cinderblock homes.

A patchwork of detention policies

Lt. Gen. Guillermo Eleazar, the deputy police chief for operations, is aware that locking up new inmates poses a threat to the safety of the prisoners and the jail staff.

The police does not want to congest the jails any further, he said, and would prefer to release violators after 12 hours. But they also need to abide by the national government’s orders and with the desire of many local officials to get quarantine and curfew violators off the streets.

The result is a patchwork of policies depending on what local governments mandate. In the city of Manila, Eleazar said, violators were freed immediately after cases had been filed. But some cities like Navotas complained “that people will not learn their lesson if the police release them.” When the police warned that a steady stream of new inmates could wreak havoc on detention centers, Navotas used schools as a temporary lockup.

Senior Supt. Baby Noel Montalvo, BJMP’s director for Health Service, said that even before the pandemic, most of those transferred to their jails were already “sick or severely ill or have symptoms of respiratory infection.” Accepting new detainees, he said, will only increase the risk of infection and compromise the safety of inmates.

The Philippines has a three-tiered prison system. The police lockups are the lowest tier. Jails run by the BJMP are for those awaiting trial, are currently being tried or serving short jail terms. Convicted prisoners who are serving sentences of three or more years are sent to facilities run by the Bureau of Corrections (Bucor).

The police, the BJMP and Bucor are using different approaches to dealing with the pandemic. The BJMP implemented the strictest measures—no new detainees and an absolute lockdown that required jail guards to stay inside jails until the quarantine is lifted. In-person visitation was restricted, and the “paabot (pass over)” privilege, where jail staff receive packages from outsiders and deliver them to specific inmates during ordinary lockdowns, was cancelled.

The lone exceptions are the jails in Northern Mindanao, where the courts are issuing commitment orders that send detainees to jails.

Less stringent at Bilibid

Bucor is less stringent in its seven facilities, including the national penitentiary known as Bilibid. Visitation rights were cancelled but the paabot system remains in place. Guards are allowed to leave prison and penal colonies after their tour of duty, which usually lasts for a week.

Unlike the BJMP, Bucor, with a current inmate population of 49,584, is still accepting new prisoners. Spokesman Gabriel Chaclag said the latest addition arrived in late March. Newly arrived detainees are evaluated for a week or two before they join other prisoners.

Bucor officials came under Senate scrutiny last year because of the alarming number of prison deaths in the national penitentiary. Henry Fabro, the chief of the Bilibid hospital, said one prisoner there dies each day. Officials blamed overpopulation for the deaths.

Chaclag insisted that social distancing was “possible” within Bucor compounds, unlike in other jails. He could not explain why that was the case, saying only that prisoners were “old enough” to decide how to implement social distancing among themselves. “Because of the information drive, they took it upon themselves to maintain their distance from one another. They no longer eat or pray together,” he said.

The risks, however, are not just that the prisoners will infect each other. Eventually, jail and prison officers will have to go home, take a rest, and recharge. When that happens, corrections staff will be exposed to the coronavirus and risk infecting the prisoners when they return. As one jail official told Narag, “One miss, we all die.”

Meanwhile, jails are preparing for the inevitable. Bilibid has prepared nine buildings for Covid-19 patients. Cities are setting aside isolation areas for infected inmates. In some, there is space for only one person; in others, isolation facilities can take 100 to 300 patients.

Money rules in Manila City Jail

The Manila City Jail has set aside an old building formerly used by tuberculosis patients as an isolation area. In addition, dorms and offices are disinfected daily, with inmates cleaning their own spaces to avoid contact with the staff.

There are 14 dormitories in the jail, all of them so overcrowded, they could not possibly take any more. The facility was built for 1,100 inmates but currently houses 4,888.

Lawrence, a former Manila City Jail detainee who asked that his full name not be revealed, said money and power rule these dormitories. Those with the means pay dorm leaders so they can sleep in private cubicles called kubols. Lawrence said a kubol measures around 2×2 meters. They are “not big but provide enough space so you can stretch your arms and feet.”

Others less fortunate take turns sleeping or sleep in crouched positions, spilling out into hallways and corridors because of the lack of space.

Lawrence stayed in Dormitory 3 for two years. At night, he recalled, one has “to tread carefully” to avoid stepping on bodies that were like landmines on the floor. “If you accidentally step on an inmate, you will get whipped several times,” he said. The number of lashes depends on the power and position wielded by the offended party.

Access to bathrooms is another luxury. “High-ranking detainees” like Lawrence can use bathrooms with showers and properly functioning toilets. Poor inmates use common toilets that even visitors are not allowed to use “because the stench gets so bad, it’s really embarrassing.” Common bathrooms have no doors, he said. They have tubs called “swimming pools” which inmates fill with water. Toilets are holes directly connected to drainage canals.

In 2016, when Lawrence was first jailed, there were only 127 detainees in Dormitory 3. He left behind 605 dorm occupants in 2018, most of them facing drug charges. Despite the lockdown, arrests of drug suspects continue.

For all the worries about the prisoners’ health, Interior Government Secretary Eduardo Año, who supervises BJMP, said jails are “the safest place right now.” Prisoners, he said, risk exposure to the virus if they were released.

“All prison detention cells are COVID-free,” he said in a statement.

Up to now, however, no jail guards or inmates in any of the Philippine jails, prisons and police detention centers, have been tested for Covid-19. #

= = = =

Aie Balagtas See is a freelance journalist working on human rights issues. Follow her on Twitter (@AieBalagtasSee) or email her at a[email protected] for comments.

Rick Rocamora is an award-winning documentary photographer and author of four photo books; Filipino WWII Soldiers: America’s Second Class Veterans, Blood, Sweat, Hope and Quiapo; Rodallie S. Mosende Story, Human Wrongs, and Alagang Angara, a book that highlights the legislative achievements of Senator Ed Angara that continues to benefit our people and nation after his passing. His work is part of the permanent collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Arts, U.S. State Department Art in Embassies Program, and private and institutional collectors. His work is widely exhibited in national and international museums and galleries, published in print and online and aired in various broadcast news outlets. In the Philippines, his work had been exhibited at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Ben Cab Museum, Vargas Museum, and Ateneo Art Gallery. His exhibition, Bursting at the Seams: Inside Philippine Detention Centers won national and international awards for Filipinas Heritage Gallery of the Ayala Museum. Before pursuing a career in documentary photography, he worked in sales, marketing, and management positions for the US pharmaceutical industry for 18 years. — PCIJ, April 2020