Before Covid-19, Philippine Jails Already a Death Trap

Human rights advocates believe that numbers will still increase and the full force of Covid-19 is yet to be felt. They also call for transparency in releasing death and infection rates to help craft policies and mitigate the spread of false information.

BY AIE BALAGTAS SEE/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

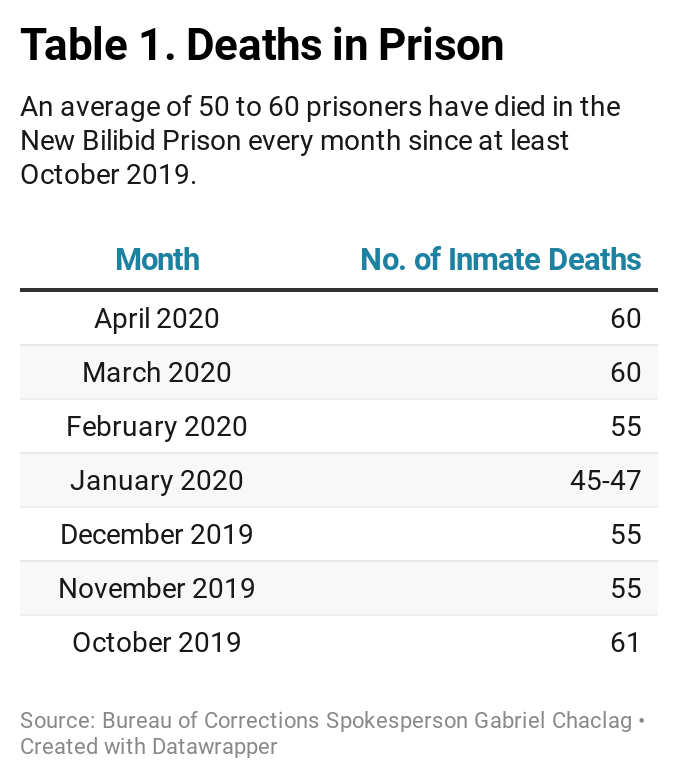

AN AVERAGE of 50 to 60 prisoners have died in the New Bilibid Prison (NBP) every month for the past six months but only one death in April has been attributed to Covid-19.

For the Bureau of Corrections (Bucor) the death toll in February, March, and April was still within the range of monthly deaths in the last quarter of 2019 to early 2020. The pandemic has ravaged the country since March, with local transmission of the coronavirus taking place as early as February. Humanitarian groups have since warned of its catastrophic effect on the country’s prison system.

“It still falls under our average death rate for the past six months,” Bucor spokesperson Gabriel Chaclag said in a phone interview.

The high death rate, Chaclag said, was proportional to Bilibid’s huge population, currently at 28,000. The population could create from 11 to 14 barangays. Chaclag claimed that if they have lower population, then they will have fewer deaths.

Bilibid is one of Bucor’s seven facilities for convicts. It had recorded one to three deaths daily from October 2019 to April 2020, noted Chaclag. Most came from the maximum-security compound, which was designed for 6,000 but currently holds 19,000 men. Chaclag said that the cause of these deaths varied, citing illnesses such as cancer and heart failure as major ones.

“Loneliness, nightmares, and accidents” were also seen as reasons for these deaths according to Chaclag.

Prisoners in extremely congested jail facilities live in deplorable conditions, lacking proper health care, hygiene, and nutrition. Human rights advocates have called for the early release of elderly and sickly detainees. They have also pushed for making available information on death and infection rates.

With Covid-19 breaching Bilibid walls, the deaths are sowing panic and paranoia among disgruntled detainees who, according to an insider, fear that the virus has already exploded within prison compounds.

The lone Covid-related death from NBP was reported on April 23. There have been no confirmed Covid-19 cases in Bilibid since, but at least 44 inmates have been in quarantine, Chaclag confirmed. Four of them were tested for the virus, with results yet to be released.

Health undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire, in a phone interview, said that only one NBP inmate had tested positive for coronavirus as of May 4.

A prison insider said bodies were piling up in NBP’s old isolation ward called Dorm 1D. In late April, at least “20 bodies emitting foul odor” were stacked there. On May 1, the insider added, three men died after the NBP hospital ran out of oxygen.

“The inmates plan to hold a noise barrage but Bucor guards threatened to shoot them,” the insider said.

Chaclag denied this, saying those “who have agenda” should stop weaving stories that sow paranoia, which could lead to a riot in NBP. Bodies were not piling up, he said. There were days when the funeral parlor could not retrieve them because the cause of death was unknown. “We had to wait for the crematorium personnel to pick them up,” he explained.

Guidelines issued by the Health department stated that deaths with unknown causes shall be treated as Covid cases and the corpse cremated within 12 hours.

Six to five NBP inmates who died in their dormitories were cremated last month. This is not a known practice in NBP. Bodies without cause of death were usually autopsied and kept by funeral parlors until someone claimed them.

Chaclag said that unclaimed bodies in the past were either buried in the NBP cemetery or were taken advantage of by funeral parlors who sold them to operators of “sakla,” a form of illegal gambling carried out during wakes to help families raise funds for burial expenses. In the case of unclaimed inmates, the earnings simply went to the pockets of the syndicates.

Old conditions and new virus, a lethal mix

Inmate deaths is a decades-old problem at the New Bilibid Prison. The global pandemic merely reopened the old Pandora’s box.

The national penitentiary was already in the spotlight last year because of the alarming number of deaths there. Henry Fabro, the Bilibid hospital chief, said one prisoner there dies each day.

Humanitarian groups have long blamed overpopulation, poor hygiene, lack of proper food, and limited access to health care for the lamentable condition. The calls to depopulate jails have only grown louder with the coronavirus now part of the equation.

Rights advocates have called for the release of vulnerable inmates, saying infections in detention areas might risk jail staff and visitors, and can potentially lead to the reinfection of the general public.

One of these advocates, Raymund Narag, an associate professor at Southern Illinois University and expert in Philippine jails, told PCIJ that there should be transparency in dealing with these problems.

“It is their moral and legal obligation to be transparent. It is the only way to mitigate the spread of false information. It is also helpful in crafting policies if information are timely and accurately provided,” Narag said.

Death and infection rates in detention facilities have always been difficult to obtain. Like Narag, Human Rights Watch has called for transparency after learning that one detainee dies every week in Quezon City Jail since the coronavirus hit the facility last March.

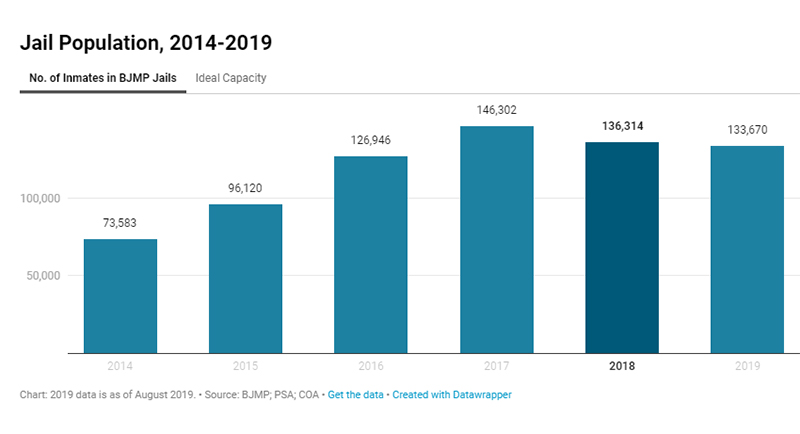

Paul Borlongan, chief doctor of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), which supervises city jails, also claims that BJMP’s death statistics is still “acceptable.”

In recent years, from 300 to 800 detainees have died in BJMP annually. “So far, I can say that our death statistics is still acceptable,” Borlongan said, adding that, “we expect 20 to 40 per week and sometimes 60 to 80 per month.”

Clash of statistics

Transparency is not the only problem. A clash of statistics among government agencies, and between the local and national governments, is adding to the confusion.

According to Usec. Vergeire, there were 249 Covid-positive inmates in jails and prisons as of May 3. Of these, 187 were in Cebu City Jail, 49 in the Correctional Institute for Women in Mandaluyong, 12 in Quezon City Jail, and one in Bilibid.

The facilities that appear to be the hardest hit are the most congested. Cebu City Jail is overpopulated by 1,000 percent and has the highest number of inmates at 6,237. Quezon City Jail is the third most crowded with 3,821 inmates as of March 2020.

As far as BJMP is concerned, only nine inmates — not 12 — from Quezon City Jail are considered Covid-positive patients. Borlongan surmised that the three other inmates in DOH’s list were those whose deaths were considered “possible Covid” cases because they had flu-like symptoms or pulmonary problems.

As of April 27, BJMP has recorded a total of 195 inmates and 34 jail staff who tested positive for Covid-19. Five jail personnel had recovered while none of the inmates have yet to be cleared of the illness. BJMP also documented cases in Mandaue City Jail, Marikina City Jail, Pasay City Jail, and Mandaluyong City Jail. These jails are not in the DOH list.

The City Reformatory Center in Zamboanga City was also reported to have Covid-positive cases. BJMP’s Borlongan said he has not received the official report about these cases.

Infections were also reported in the Cebu Provincial Jail, which is managed by the local government.

A Bucor official, who requested anonymity, also complained of slow and unreliable test results from the Health department. “We have to repeat the test each time they release results to us. It’s a waste of resources. Once, our staff tested positive but when the Philippine Red Cross rechecked it, the results were negative.”

The World Health Organization, International Committee of the Red Cross, and the Health department are working alongside Bucor and BJMP in setting up quarantine facilities for infected detainees.

DOH Undersecretary Vergeire said they also plan to “conduct targeted testing, provide treatment and management of cases, and ensure that infection control measures are in place to prevent the spread of Covid-19 in penal and correctional facilities.”

Prisoner release and other urgent calls

From March 17 to April 29, almost 10,000 inmates have been released as bid to curb the spread of coronavirus in jails. The Supreme Court has also allowed the release of pre-trial detainees in jail for crimes punishable with six-month incarceration and below. A reduction of bail has been recommended for non-convicts facing charges punishable with jail time of six months to 20 years.

Petitions seeking temporary freedom for the sick and elderly are still pending approval.

Last March, Interior secretary Eduardo Año rejected calls to release vulnerable inmates, saying jails were the “safest” place for them. The growing number of Covid-19 cases now appear to disprove this claim.

“If many people — prisoners, guards, their families, the people i[n] neighborhoods around jails— die because of Covid-19, the massacre is squarely the responsibility of government,” Human rights advocate and Ateneo de Manila University professor Antonio La Viña said.

Narag and La Viña believe the numbers will still increase and the full force of Covid-19 is yet to be felt. “I believe that there will be multiple bombs that will explode. Many PDLs [persons deprived of liberty] had been dying from many jails… only that it is not reported as such. But once the news report will catch up, I will not be shocked,” Narag said.

Warnings about the coronavirus being a bomb that could explode in jails and prisons were made in early March. These fell on deaf ears until infections began to manifest, with jails and prisons fast becoming the next epicenters of the virus. “Our prisons will be ground zero unless we decongest now,” said La Viña.

Narag and La Viña are urging the government to take swift actions, stressing that the disease’s spread is a public issue and not only the problem of the corrections and prison system. “We are already faced by a problem that can kill us all,” Narag said.

Aie Balagtas See is a freelance journalist working on human rights issues. Follow her on Twitter (@AieBalagtasSee) or email her at [email protected] for comments.

Photograph by Kimberly dela Cruz— PCIJ, May 2020