By Sonny Africa

The Duterte government insists that it is successfully responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. The reality is a little bit different – it hasn’t done enough, and is planning to do even less.

The coronavirus is spreading faster than ever. It took over three months to reach the first 10,000 confirmed cases but less than a week to add the last 10,000, at over 57,000 to date. University of the Philippines (UP) researchers forecast between 100,000 to 131,000 cases by the end of August.

Characteristically, the government’s containment measure of choice was a military lockdown – among the fiercest and longest in the world. It justified this as harsh but necessary, repeating a favored talking point used to justify all sorts of sins.

The effect on the economy and the people was certainly brutal.

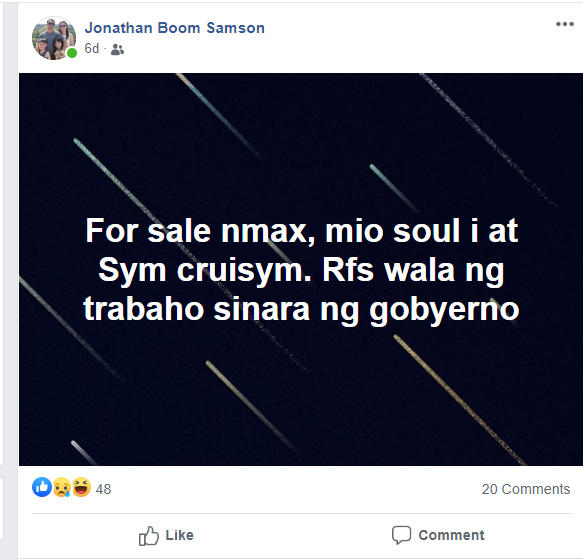

The country was plunged into the worst crisis of mass unemployment in its history with 14 million unemployed and a 22% unemployment rate in April 2020, by IBON’s reckoning. The combined 20.4 million unemployed and underemployed are over two-fifths (40.2%) of the presumed labor force. These correct for serious underestimation in officially released figures.

The joblessness and collapse in livelihoods are expected to ease as restrictions are relaxed. But whatever improvement will still not be enough to return to a pre-pandemic state.

The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is projected to contract by 2.0-3.4% for the whole of 2020, according to the government’s Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC). The World Bank has a slightly more optimistic projection of -1.9% while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) see it worse at -3.6% and -3.8%, respectively.

This will be the worst growth performance in 35 years since the -7.3% (negative) GDP growth in 1983 and 1984. But if the low estimates materialize, it will also be the biggest decline from positive growth ever recorded.

As it is, the economy is well on the way to its fourth straight year of slowing growth. It already contracted at -0.2% growth in the first quarter of 2020 with just two weeks’ worth of lockdowns. The second quarter figures that will come out in August will be much worse.

Unhealthy response

No one is likely to have thought that the worst public health crisis and economic decline in the country’s history would be enough to spur the Duterte administration to reform its anti-democratic and anti-development ways. It didn’t.

The government’s military-dominated COVID-19 response team has proven unfit for purpose and the steeply rising cases today point to the protracted lockdown being squandered. Yet the rise in reported cases do not even give the complete picture.

To date, there’s a validation backlog of over 15,000. The positivity rate of 12.4% meanwhile indicates that testing is still, months into the pandemic, far below the levels needed. Local transmission is still gaining momentum even as other Southeast Asian countries have already stopped theirs.

The hazy picture is a poor starting point for the contact tracing, isolation and selective quarantines needed. But the rise in COVID-19 cases is sufficient to show how social distancing and other precautionary measures can’t go far enough.

Assuming all pandemic-related deaths are accounted for, the 1,534 reported deaths are still relatively few and the number of daily fatalities fortunately fewer than the peak in March. This may however soon change as the virus spreads in the coming weeks and as the health system becomes overstretched even just by those who can afford it.

Hospital capacity hasn’t been beefed up so much as portions of it carved out at the expense of non-COVID-19 cases. The National Capital Region (NCR) and Cebu are the pandemic’s epicenters in the country. As much as 19 NCR hospitals are at or nearing their capacity of ICU beds for COVID-19 patients – 14 of which were acknowledged by the Department of Health (DOH) last week – while Cebu’s hospitals are already overwhelmed.

Hyped assistance

The inadequacy of the health response is more disturbing in how the time for this was bought with lost incomes, small business closures, joblessness and hunger. Tens of millions of Filipinos even suffered more than they should have because of similarly inadequate emergency relief.

At the start of the lockdowns, 18 million beneficiary households were promised Php5,000-8,000 in monthly cash subsidies for just two months. That right there is an immediate problem – the lockdowns are running on four months now, since mid-March, with only partial easing in June.

Emergency subsidies reportedly reaching 19.4 million beneficiaries under various programs of the departments of social welfare, labor and agriculture sounds impressive.

However, the aid was very slow in coming. Most beneficiaries had to wait 6-10 weeks before getting their first monthly tranche.

The aid is also very stingy. Taken altogether, the first tranche of the cash subsidy programs only amounts to an average of Php5,611 per beneficiary family. Over the last four months this comes out to just Php11 per person per day.

The government has even recanted and said that only 12 million beneficiaries will get the second tranche. But the number of those who will actually get this second tranche may be even less than that. The government is invoking bureaucratic difficulties to explain why only 1.4 million of the 12 million have received this tranche to date.

These emergency cash subsidies are also much lower than the latest official poverty threshold of Php10,727 monthly for a family of five. Yet this miserly relief will even seem generous in the period to come because little more is forthcoming. The official government policy was succinctly put by the presidential spokesperson recently: “We cannot afford to give ayuda (aid) to keep everyone alive.”

Business as usual

The Duterte administration’s lockdowns precipitated what may be the greatest economic collapse in Philippine history. The lockdowns per se are of course temporary – indeed, as too the pandemic, even if this will linger for at least another year or more.

Though temporary, the simultaneous demand and supply shock to the Philippine economy, other countries, and the global economy as a whole is unprecedented in the modern era. The world economy is said to be undergoing its worst recession since the Great Depression.

Yet apart from a momentary surge in emergency relief and despite lip service to the economic crisis, it bizarrely still seems to be business as usual for the economic managers. There are a couple of reasons for this.

The most basic is how the economic managers – and most of our political leaders – are blinded by the free market dogma imbibed over four decades of neoliberal globalization. There is a rigid faith that market forces will be enough to meet the pandemic-driven economic challenge. This is matched by an inability to grasp that responsible state intervention is needed not just to deal with the crisis but for long-term national development.

But there is also an extreme narrow-mindedness common among many afflicted by that dogma – that ‘creditworthiness’, ‘competitiveness’ and ‘investor-friendliness’ are not just a means to but actually ends of development. The people who make up the majority of the economy are peripheral and ever in the margins.

These go far in explaining the lack of urgency and, apparently, seeing the current crisis as an inconvenient but minor speed bump on the highway to free market-driven progress.

Fragments of a response

Genuine attention would start with immediately coming up with a plan fitting the vastly changed pandemic-driven crisis conditions. Nearly six months into the pandemic, all that the people have are fragments – including fragments which are self-evidently exaggerated to give the impression of substantial action.

The economic team came up with a “4-pillar strategy” in April that was eventually rebranded as the Philippine Program for Recovery with Equity and Solidarity (PH-PROGRESO). Supposedly worth Php1.7 trillion or an impressive 9.1% of GDP, this figure was grossly bloated by double-counting of interventions and their sources of financing, by conflating actual spending with merely foregone tax and tariff revenues, and by including additional liquidity from monetary measures.

The Inter-Agency Task Force Technical Working Group for Anticipatory and Forward Planning (IATF-TWG for AFP) released its We Recover As One report in May. This seemed more detailed, comprehensive and forward-looking. There are some relevant health and education measures.

But some very important measures are missing – expanding the public health system, social protection to help everyone in need, and protecting jobs, wages and workers’ rights. Trade, industrial and agricultural measures also seem oblivious to unsound fundamentals, the global crisis, and accelerating protectionism. On the other hand, unfunded feel-good platitudes are aplenty.

The economic managers started working with Congress on a Bayanihan 2 bill in June. This replaces the Php1.3 trillion package that Congress originally proposed but which the finance department summarily shot down ostensibly for lack of funds. The Bayanihan 2 proposal is now just one-tenth in size at Php140 billion.

At present, the stinginess of the economic managers is the biggest binding constraint to addressing the pandemic, alleviating economic distress of poor households, and economic recovery. The Php140 billion is much too small compared to the magnitude of the crisis at hand. At the same time, the sweeping insistence on infrastructure as a magic bullet and on sacrosanct debt servicing means continued unproductive spending rather than on what would have the greatest development impact.

A Philippine Economic Recovery Plan was supposed to be made public at the pre-SONA forum of the economic and infrastructure cluster on July 8. But this was not presented and is still strangely kept secret. Neither the Department of Finance (DOF) nor the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) websites share this with the public, and a direct request was declined.

It’s five-and-a-half months since the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the Philippines, and about four months since declaring a public health emergency, a state of national emergency, and the start of lockdowns. The Duterte administration has throughout portrayed itself as doing everything it needs to.

In reality, it seems to be doing as little as it can. A new anti-terrorism law was apparently even seen as more urgent than clinching a stimulus program. This languid COVID-19 response is bringing us to the edge of the precipice on both the health and economic fronts. #

= = = =

Kodao publishes IBON articles as part of a content-sharing agreement.