STATE OF PHILIPPINE MEDIA 2020: Journalists Struggle to Cover the Pandemic as Space for Media Freedom Shrinks

The shutdown of ABS-CBN, the country’s largest media network, is the latest in a series of attacks and threats against the Philippine press.

BY ANGELICA CARBALLO PAGO/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

MEDIA freedom and free expression have become casualties of the “war” against the Covid-19 pandemic that has led to severe restrictions on news coverage and economic difficulties for newspapers, media advocates said on Monday.

Members of the Freedom for Media, Freedom for All (FMFA) Network cited arbitrary arrests and a growing crackdown on dissent on social media amid enhanced community quarantine measures, in a virtual forum that tackled the annual “State of Media Freedom in the Philippines” report.

The forum was held a day after the commemoration of World Press Freedom Day, and on the eve of the shutdown of ABS-CBN, the country’s largest media network, by state regulators.

‘Not just a metaphor’

Speaking at the online forum, Melinda Quintos-De Jesus, executive director of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR), noted that the government response to the pandemic has been depicted as a war.

“But that is more than just a metaphor because the military and police have been put in the frontlines as visible implementors,” de Jesus said.

International media watchdogs have noted that all over the world, the pandemic has restricted space for freedom of expression. The Philippines is no exception, with Congress passing Republic Act 11469 or the “Bayanihan to Heal as One Act,” which gave President Rodrigo Duterte emergency powers to quickly respond to the Covid-19 outbreak.

The emergency law penalizes “fake news” under a general provision that is open to misinterpretation and abuse.

An example is the case of an overseas Filipino worker in Taiwan, Elanel Ordidor, whose deportation was sought by labor attaché Fidel Macauyag over a social media post criticizing the President. Taiwan has since rejected the request.

The forum also took note of accreditation measures imposed by the Inter-Agency Task Force for Management of Emerging Infectious Disease, which have expanded bureaucratic control over the media.

Nonoy Espina, president of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), said local governments were implementing their own media accreditation schemes, citing Negros Occidental province and Bacolod City.

“This added requirement affects how we gather and how we deliver news, because (if access to) information is controlled, it can be very difficult to do journalism,” Espina said.

During the open discussion, Pulitzer Prize winner Manny Mogato said: “One of the biggest threats to journalism is government propaganda when it hijacks the narrative of the public health crisis by making it appear it was doing a good job of responding to the coronavirus pandemic.”

Attacks on media

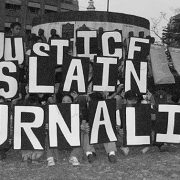

In the annual media freedom report, the CMFR and NUJP documented 61 incidents of threats and attacks against the press, including the deaths of three journalists, for the period January 2019 to April 2020.

The State of Media Freedom in the Philippines report also covered the release of the December 2019 ruling that convicted those behind the Ampatuan Massacre, which claimed the lives of 58 people, including 32 journalists, in November 2009.

MindaNews’ Antonio La Viña, former Ateneo de Manila School of Government dean, said the long-delayed court decision on what is considered the world’s single deadliest attack on journalists, was a “good ruling, with a lot of shadows — the role of political families in the Philippines that is linked to impunity.”

“We need to make sure another massacre will not happen again,” he said.

Apart from CMFR, NUJP and MindaNews, the FMFA network includes the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) and Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ).

An epidemic of experts

Tech entrepreneur and data ethics advocate Dominic Ligot, a member of the PCIJ board, urged journalists to counter Covid-19 disinformation by being on the lookout for politicization, “armchair epidemiology,” the mushrooming of experts, and the need for critical discourse.

Journalists, he said, should challenge experts and even question the assumptions underlying disease transmission models and projections.

“We are in an interesting time when everyone is in a physical lockdown and at the same time, everyone is wired up digitally,” he said.

For the first time, he noted, the public has been given access to a barrage of scientific and technical information on social media, pointing to numerous policy notes published on Facebook.

Ligot warned that journalists scrambling for expert opinion could contribute to disinformation by highlighting imprecise data or incomplete forecasts.

“We are in an environment where everyone is suddenly an expert,” he said.

Journalists need help, too

NUJP’s Espina also raised safety issues and economic difficulties confronting journalists, particularly freelancers and provincial correspondents, since the start of the lockdown.

“The biggest problem, especially for freelancers and correspondents working in small outfits, is the lack of support in covering the pandemic,” Espina said.

Espina said these journalists were left to pay for their own personal protective equipment, vitamins, and other out-of-pocket costs.

“One correspondent I have talked to said, ‘I have no idea if we’re getting a hazard pay,’ and the outfit that she works for made no mention about it,” he said.

The drastic cutdown in television programs and operations was also a huge blow to contractual media workers in the broadcasting industry who are usually under a “no work, no pay” arrangement, Espina said. With the crisis cutting on already falling revenues, closures and layoffs might be inevitable, he warned.

This was echoed by Ariel Sebellino, executive director of the Philippine Press Institute, who said that about half of the organization’s members, mostly family-owned community papers, have ceased printing due to economic losses caused by the lockdown.

“We must all get our acts together and respond to the needs of community journalists during this pandemic,” Sebellino said. “There must be a concerted effort to help improve the situation of our journalists in the provinces.”

Espina said he had received complaints from journalists who were unable to receive cash aid from the government’s Social Amelioration Program, the Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers (TUPAD) of Department of Labor and Employment, and other forms of government assistance, because of misconceptionsthat media workers were making a lot of money.

An overlooked aspect is the pandemic’s toll on the mental health of journalists who are, in a way, also frontliners in the Covid-19 response, Espina said.

“None of us is immune to the fear and uncertainty that the pandemic brings,” Espina said. “We need to recognize that we are not superman. We need to take care of ourselves.”— PCIJ, May 2020