Posts

STREETWISE: #BigasHindiBala by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao Productions(Photo from Kilab Multimedia)

Streetwise

The violent dispersal by the police of the 6000-strong protest by farmers and lumad (indigenous people of Mindanao) in Kidapawan, North Cotobato last April 1 could be dismissed as just another incident in the long list of clashes between state security forces and citizens airing their grievances against government.

But this is different. This has the potential to explode in the face not just of Liberal Party Governor Lala Talino-Mendoza and the local police but that of the lame-duck President Benigno Aquino III and his anointed one, presidential candidate Mar Roxas, barely six weeks before the national and local elections on May 9.

The farmers were demanding rice and the release of calamity funds in the wake of the severe drought in their farm lands wrought by the El Niño weather disturbance. They were met with truncheons, bullets and water cannon. The result, as of this writing: three protesters confirmed killed by gun shot, more than a hundred wounded, scores arrested and hundreds more still under siege by the police in a Methodist church compound where they sought sanctuary.

There is no disputing that the farmers had a legitimate reason for massing up on the national highway to dramatize their plight and to force government to act. Hunger stalked their families and their situation had become increasingly desperate with their farms reduced to scorched earth. They were already deep in debt because of their failed harvest and had no money to buy food. There was hardly any relief in sight despite the provincial government’s declaration of a state of calamity.

In response Gov. Mendoza reportedly announced that the farmers would be rationed three kilos of rice each for three months. (Of course, their status as her “legitimate“ constituents would still have to be verified.) Having exercised “maximum tolerance” of the farmers’ protest, she then ordered the police to clear the highway of demonstrators purportedly to restore law and order and to “rescue” the children that the farmers had brought along since no one would be left to look after them in their homes.

The result was a massacre akin to the massacre of peasants demanding land reform during the administration of the first Aquino president, Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino. It also brought back memories of the Hacienda Luisita massacre when sugar mill and plantation workers in the Cojuangco-owned hacienda were killed while demanding higher wages and genuine land reform. The hashtag #BigasHindiBala (#RiceNotBullets) captures the farmers’ demands amidst the government’s resort to fascist state violence.

All the presidential candidates condemned the violence that had taken place in Kidapawan and the resulting deaths and injuries. Notably four “presidentiables” – Senator Grace Poe, Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, Mayor Jejomar Binay and Senator Miriam Defensor – explicitly condemned the use of deadly force by the police and called for punishment of those responsible. They also castigated the Aquino administration for failing to provide timely and adequate relief to the distressed farmers considering that the severe drought and its effects on agriculture had been predicted for more then two years by the government weather agency.

Aquino’s candidate Mar Roxas, however, could only condemn the violence that attended the protests in general, without specifying who was responsible. Roxas also called on the Philippine National Police to investigate, a surefire formula for a whitewash, as had happened in all the violent dispersals at demonstrations that had previously taken place.

Neither did he take the pertinent government agencies (such as the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Social Work and Community Development) and his Liberal Party-mate Gov. Mendoza to task for failing to proactively address the farmer’s plight. To do so would be to criticize the kind of governance he has extolled as exemplary and which he has promised to continue should he win.

Mayor Duterte went the extra mile by mobilizing the people of Davao and the city government to collect and send sacks of rice to Kidapawan. It is said that Senator Poe also quietly mobilized her supporters to send their contribution as did private individuals such as film actor Robin Padilla.

These humanitarian acts however did not sit well with Gov. Mendoza as she denounced them as “insulting” (to whom we wonder, certainly not to the starving farmers and lumad) and motivated by “politicking” (referring to Mayor Duterte who the governor accused of trying to look good at her – and we suppose her presidential candidate’s – expense).

President Aquino has chosen to remain silent on the Kidapawan crisis but police statements as well as that of Communications Undersecretary Manolo Quezon a day after the massacre indicates what the official line will be.

First, that the protesters rained rocks on the police and the police were only forced to respond. (Quezon is silent about why police were armed with high-powered rifles and were seen on video footage to be aiming and shooting at the farmers.)

Second, that “militant groups of the Left” were the ones who had mobilized the farmers which makes the protest suspect. (Quezon conveniently glosses over the fact that such organizations had been openly, consistently and yes, militantly, been supporting farmers on such issues as landlessness, government neglect of calamity victims and militarization of rural communities leading to grave human rights violations. That they were visibly supporting the farmers at the Kidapawan protest is nothing new nor sinister except to government officials who would resort to red-baiting to shift attention and blame from themselves.)

Third, that initial police investigation indicated the presence of armed men among the protesters proof of which is the alleged finding of traces of gunpowder on the hands of one of the dead farmers. Police also intimated to media that an NPA commander had been arrested but would not give any name. Quezon for his part mentioned “cadres” in the protest to lend credence to his claim that Leftists were behind the protests and the ensuing violence. (If indeed the protesters were armed why did not a single policeman suffer any gunshot wounds? Moreover, the police search of the Methodist church compound did not come up with any guns or deadly weapons. In fact the farmers’ feared that these would be planted by the police and would be used in trumped-up charges against them.)

We can only conclude that the official cover-up has begun. Together with a completely made-up police version of what happened and manufactured ”evidence” to support it, Malacañang spin-masters are already resorting to red-baiting, victim-blaming, and opposition candidate-bashing to cover up the underlying cause of the Kidapawan massacre.

It is nothing less than a government run by bureaucrat capitalists whose main purpose in life is to promote their own interests and those of the entrenched elite – mainly big landlords and comprador capitalists – against the interests, rights and welfare of the majority of the Filipino people especially landless and destitute farmers.#

(The second of this column’s two-part series on the Philippine health care system has been set aside in consideration of the more pressing issue of the Kidapawan massacre.)

Published in Business World

4 April 2016

STREETWISE: Philippine health care system, from bad to worse by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsStreetwise

A country’s health care system is a sensitive indicator of how government values the health of its people, underscoring the truism that the people痴 general health constitute the very foundation of socio-economic development and ultimately, the people痴 wellbeing and happiness.

Even as a medical student more than three and a half decades ago, it was already starkly clear to me that the Philippines health care system was sick. It was a dual system: one for those who could afford to pay; another for those who could not. One was private, the other public.

On the whole, private health care was of better quality in terms of facilities and personnel although one could find substandard care in private hospitals because of poor regulation and the overriding motivation to turn a profit rather than provide a badly-needed social service. The public system sufficed for the majority of the population who had little choice when stricken by disease except to avail of what was available and affordable

regardless of quality.

These hospitals and clinics were clustered in urban centers. The tertiary centers or the most well-equipped with the widest choice of specialist doctors would be found in Metro Manila. In the rural areas, people continued to live and die without ever seeing a nurse much less a physician because health care was absent or inaccesible, physically and financially.

Of coure there were the crown jewels of the Marcos martial law era, the Heart, Lung and Kidney Centers and the Philippine Children痴 Medical Center that were part of the showcase edifices of First Lady Imelda Marcos but that痴 another story.

In time, with the growing social inequality, there was hardly room left for anything in

between as even the not-so-rich but not-yet-miserably-poor started to avail themselves of public hospitals to avoid dissipating their life savings on health care. That was when the so-called middle class could be seen in the Philippine General Hospital痴 charity wards or, at best, its more affordable but scant private rooms.

As the cost of curative care soared (after all everything, from the simplest syringe to the state-of-the-art diagnostic machines, is imported) and the public health budget became tighter due to chronic misprioritization, the trend towards charging fees for laboratory procedures and making patients buy their own supplies became the norm even among supposed 田harity・patients. (Government hospital pharmacies are notorious for always running out of medicines and supplies so that patients have to buy from private boticas located just outside the hospital premises.)

Meanwhile, most public hospitals in the urban centers continued their slide towards decline and decay, starved of government subsidy. Brain drain among poorly paid health personnel was the rule rather than the exception, mitigated only by the vagaries of the market for nurses and doctors abroad. The negative effects included a constant turn-over of hospital personnel even in critical-care units requiring highly-trained staff.

Private hospitals continued to do brisk business catering to the country痴 elite but became more and more unaffordable to the shrinking middle class. Medical health insurance for the regularly employed through the old Medicare covered only a small portion of hospitalization costs such that out-of-pocket expenses ballooned uncontrollably.

Clearly the system could not remain the same – inaccessible and unaffordable to the vast majority because it was urban-centered, curative care-oriented, and dualistic. Health reform was urgently needed but what kind?

Apparently government heeded World Bank recommendations that were geared towards reforming how health care was to be paid for, less from scarce public funds and more from the private pockets of patients and their families. The assumption was that there were far too many freeloaders availing of the public health care system when it should be focussed on providing services only for the very poor (who now have to prove their state of indigency).

The trend towards commercialization of medical services and eventually the privatization of entire public hospitals stealthily crept up on the unsuspecting public. The shining examples held up to policy makers of how a government hospital can be top-of-the-line without being a drain on the national health budget are the National Kidney and Transplant Institute and the Philippine Heart Center.

These public hospitals have spanking new facilities for pay patients while maintaining some beds for charity patients. They have leased portions of hospital property to private businesses such as shops and restaurants. They seem to have resolved the problem of financing their operations by increasingly catering to pay patients and relying less on government subsidy.

Under the Aquino administration the acceleration of privatization and commercialization of public hospitals reached a new high with the targeting of a slew of hospitals for conversion into public-private-partnership projects.

Prime example is the National Orthopedic Hospital that was slated to be auctioned off to the highest bidder for conversion into a modern, state-of-the-art facility. This would have meant throwing out the thousands of charity patients depending on the old ramshackle facilities and leaving them willy-nilly to their own device to get adequate medical assistance. Only the united opposition of patients, health reform advocates, hospital staff and administration as well as social activists and sympathetic media practicioners prevented the corporate take-over.

In the meantime the government has been overhauling the national health care insurance system called Philhealth. The claim is that there is now close to universal coverage with more than ninety per cent of the population able to avail of health insurance.

Are these the wide-ranging and fundamental health reforms our people have been waiting for? Or are they merely exacerbating the deteriorating health situation of our people by denying them access to basic and life-saving health care? #

Next week’s column takes a critical look on Philhealth.

Published in Business World

28 March 2016

STREETWISE: Letter to a grandson on “people power” and revolutionary change by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao Productions(Photo from Bulatlat.com)

Streetwise

Dear Grandson,

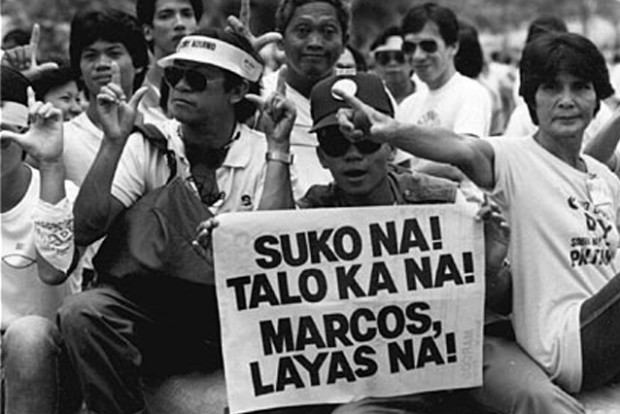

I thought I would write to you and try to explain what EDSA I was all about. The idea came up with all the recent talk about how your parents’ generation does not understand, much less appreciate, what happened thirty years ago, at the “people power” uprising that brought down the brutal and rapacious Marcos dictatorship.

Although I don’t necessarily agree with that sweeping statement, there is some truth to it. Your parents were too young then to really know what was going on. Then they grew up seeing that while the dictator himself was gone, not much else seems to have changed. This experience can be very frustrating and conducive to cynicism and even apathy.

So I thought at the very least, I owe it to you, to do some explaining why our country seems stuck in a rut; economic opportunties are limited; social problems continue to pile up; politicians are a hopeless lot; and many of your uncles and aunts and their friends have decided the only solution is to go abroad to find a decent living and a safer place to raise their families.

At the outset, I must tell you not to take the basic freedoms you enjoy today for granted — freedom of speech; freedom of the press; freedom to rally and petition the government for redress of grievances.

While there are still many unwarranted restrictions on these freedoms today, the point is we absolutely didn’t enjoy them under martial rule. (At least not until many years later, when people had become angrier, more courageous, and better organized such that they began to assert these freedoms regardless of the consequences.)

Most organizations of the people were banned. Student councils and publications were especially targetted; the dictatorship knew that universities are the hotbeds of radical ideas and dissension. Only the Marcos-controlled political party, the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) was allowed to exist and rule the stamp-pad parliament.

Defiance of Marcos’ iron rule could mean getting abducted and “salvaged” (outrightly killed without any legal due process); or getting arrested, tortured and spending years in detention without any charges or trial. There were no courts to turn to; no independent newspapers or tv stations where you could expose wrongdoing. No, you couldn’t use social media either; it didn’t exist then as you know it now.

The lower classes bore the brunt of the repression such as peasants fighting landgrabbers and demanding that land be given to those who work on it and not to absentee landlords; workers striking over starvation wages, poor working conditions and the right to form unions; indigenous peoples defending their ancestral land from mining companies and plantations; and urban poor fighting demolition of their shanty towns to give way to shopping malls and so-called development projects.

What is being hailed as the “people power revolution” brought down this repressive rule thirty years ago. All over the country, but most dramatically at the Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), the highway between two large military camps where former Marcos henchmen and mutinous military men had holed up, the people rose. They filled EDSA, Mendiola and other thoroughfares in urban centers with their warm bodies for four days until the Marcos family abandoned the presidential palace using helicopters provided by the US government.

It was a heroic undertaking. It took fourteen years – and tens of thousands of lives sacrificed in fighting the dictatorship – to get to that point.

Don’t believe it when they tell you that EDSA was only about Cory Aquino, Cardinal Sin, Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, General Fidel Ramos and the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) rebels and their avid followers.

Don’t believe it either when they tell you the Left or the activists from the nationalist and democratic movement were absent at the four-day “people power” uprising. The Left formed the core of the aboveground and underground opposition, consistently carrying the anti-dictatorship movement forward all throughout the dark years. Your grandparents were part of that movement.

Getting rid of the dictatorship was certanly a big improvement but it was not enough. It wasn’t enough to just change leaders, to shift from the old rulers, the Marcoses and favored oligarchs, to the new ones, the Aquinos and their coterie.

Poverty, hunger and ill health are still rampant and widespread, the everyday condition of majority of Filipino families. They are the landless peasants and displaced indigenous peoples; lowly-paid workers and employees with no security of tenure; and the rest of the people who can’t find work or decent sources of livelihood, who are increasingly going abroad as OFWs, becoming odd-jobbers or turning to criminality to survive.

Society’s resources are still monopolized by the landed and big business elite in partnership with multinational corporations and banks. Political power remains in the hands of the oligarchy whose objective is to maintain the status quo utilizing deception and coercion. Periodic undemocratic elections allow their political dynasties to take turns getting richer from graft and corruption. Government officials are subservient to foreign interests, principally the Philippines’ former colonizer, the US of A, that impose anti-people and anti-national policies and programs.

The educational system, mass media outlets and culture as a whole keep the majority of the poor submissive and resigned to their “fate”.

Philippine society — its economy, political and cultural systems — has been in the throes of crisis for a very long time, needing nothing less than a complete, revolutionary overhaul. But EDSA I was not a social revolution in the true sense of the word. The national situation did not change post EDSA I because the promised reforms were never undertaken. The elite who benefitted from EDSA were also the principal defenders of this unjust and decadent system.

That much has become clearer as the years have passed, with six presidencies, several coup attempts, two long-running armed conflicts and another “people power” uprising taking place.

So, dear “apo”, the fight for fundamental reforms in society and government continues long after EDSA I. It is now your parents’ generation – and soon enough – your own generation that will have to take on this historic mission of achieving our people’s great aspirations for prosperity, equality and genuine freedom and democracy.

I sincerely hope, that in due time, you will awaken to this challenge and embrace it. A life of meaning and fulfillment awaits you.

Lovingly,

Lola

Published in Business World

29 February 2016

STREETWISE: Legacy of EDSA “People Power” by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsThe reputation of the EDSA “People Power” uprising has been getting a beating these past thirty years, especially with an EDSA Dos and even a so-called EDSA Tres following the original phenomenon.

Criticisms range from valid to outlandish. That it merely installed another corrupt, elitist regime and brought back, or even worsened, the ills of the old society premartial law. That it was manipulated by vested interests and shadowy forces. That it was basically mob rule, the anti-thesis to democratic elections that oversee the orderly transition from one regime to another.

Worse, a significant number of young people have been hoodwinked into believing that the US-backed Marcos dictatorship was a a kind of benevolent strongman rule that the present crisis-ridden Philippine society sorely needs to set things aright.

It has been said that Marcos’ imposition of martial law signified the inability of the ruling elite to rule in the old way. Philippine society then was in the grip of another intense socio-economic and political crisis that was but an exacerbation of the long-running crisis of the backward, poverty-stricken, unjust and inequitous social system.

The factional conflicts among the elite could no longer be settled through periodic electoral contests. President Ferdinand Marcos was ending his second term in office and was barred from running again. The infamous Plaza Miranda bombing of the Liberal Party’s leaders was blamed on Marcos. Marcos in turn blamed the communists and his nemesis Senator Benigno Aquino.

Two nascent armed revolutionary movements, one led by the Communist Party of the Philippines and the other by the Moro National Liberation Front, were fast gaining adherents in the countryside. In the urban centers, strikes and demonstrations by workers, students and the urban poor were growing in frequency and militance, mobilizing tens of thousands. They called for and end to the “basic problems” of imperialsm, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism and the overthrow of the “puppet fascist” Marcos regime.

Marcos’ brutal authoritarian regime lasted fourteen years laying waste the best and brightest of a generation of youth who joined the resistance movement and hundreds of thousands of other human rights victims — from such prominent martyrs as Ninoy Aquino, Edgar Jopson, Dr. Johnny Escandor and Macliing Dulag — to ordinary people who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

It brought the economy to ruin by plundering the public coffers in cahoots with its business cronies and favored multinational corporations and by entering into onerous loans and contracts that would take decades for our people to pay off.

It transmogrified the already fascist military and police forces into the dictator’s private army and

into even more abusive and corrupt institutions. It treated the First Family akin to royalty and instituted one of the most entrenched political dynasties this country has had the misfortune of having.

To ensure continued backing from the US government, international financial institutions and the foreign chambers of commerce, it did their bidding in terms of anti-national and anti-people economic policies and programs. The linchpin was Marcos’ maintenance of the US military bases and subordination of Phillipine foreign policy to US dictates.

The EDSA “People Power” uprising signified the end of the Marcos dictatorship because of the magnitude and depth of its crimes against the Filipino people.

Exploitation, oppression and repression breed resistance. This resistance had been building up from the moment martial law was declared — armed and unarmed, in the cities and the countryside, among the people and the disaffected elite, and across the political spectrum from Left to Right as Marcos became increasingly isolated.

Ninoy Aquino’s assasination sparked public outrage that led to mammoth demonstrations. The political crisis pushed Marcos’ erstwhile backer US President Ronald Reagan to pressure Marcos to call for snap elections. Corazon “Cory” Aquino was declared the winner by the people but Marcos had himself inaugurated as president. Cardinal Sin and Cory Aquino called for civil disobedience. The situation threatened to develop into an uncontrollable political confrontation between the US-Marcos dictatorship and the broad anti-dictatorship united front.

The Enrile-RAM aborted coup d’etat triggered the EDSA uprising when people from all walks of life spontaneously poured out into the highway fronting the two military camps to act as a buffer against Marcos loyalist troops and the Enrile/Ramos-led mutinous forces. They were there not for the love of Enrile or Ramos but for their burning desire to oust Marcos and write finis to the dictatorship.

Cory Aquino was physically not at EDSA during the four-day uprising. Corystas conveniently forget this fact when they gleefully point to the inability of Left forces to position themselves prominently at EDSA because of their preceding error of boycotting the snap elections.

But it would be the height of dishonesty and political naivete to say the Left did not play a role in the uprising — before, during and after. As a matter of fact, national democratic activists of workers and students were already at Malacañang’s gates as the Marcos family prepared to evacuate courtesy of the US military.

Moreover, a cursory perusal of the names of the martyrs at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani and the martial law victims who won a landmark class suit against the Marcos estate would show indisputably that the vast majority belong to the Left, under and aboveground.

For the Left, EDSA “People Power” has left a worthwhile legacy of a united and militated Filipino people rising up against the dictatorship and overthrowing it. Unfortunately its powerful democratic impetus was hijacked and coopted by the anti-Marcos reactionaries this time led by the US-backed Corazon Aquino regime.

The promise of meaningful reform was reneged upon. Militant mass mobilizations were suppressed once more. Peace negotiations with revolutionary movements were sabotaged and jettisoned. “People Power” rhetoric was invoked to rally support for the reactionary government and to entrench the reactionary status quo. Is it any wonder that “People Power” has gained such an unsavory reputation among the people, especially the youth, leading to confusion, alienation and even cynicism?

We need to strive harder for our people to learn the hard lessons of the EDSA people’s uprising — the need for fundamental and not just cosmetic change and the indispensable requirement of continuously expanding and consolidating genuine people’s organizations to accomplish this.

In due time, the awesome power of a united people can once more be ranged against the feckless power of the ruling elite in the ultimate showdown. #

Published by Business World

22 February 2016

STREETWISE: Remembering EDSA “People Power” by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao Productions

(Photo from www.philstar.com and owned by Gerardo Joaquin Sinco)

Streetwise

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana

From February 22 to 25, the nation will be marking the thirtieth year of the people’s uprising that toppled the US-backed Marcos dictatorship dubbed EDSA “People Power”. Ironically, this event will take place even as Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr, the son of the fascist dictator, attempts a spectacular return to Malacañang should he win as vice president in the coming May elections.

Indeed the Marcos dynasty is back with a vengeance.

The Marcoses have been able to hide and launder a substantial part of the billions that they plundered. They have leveraged the political patronage ladled by the dictator on the Ilocos region to reestablish their political bailiwick in the North. (Former First Lady Imelda and daughter Imee have managed to win congressional seats; the dictator’s namesake became governor and now senator giving up the gubernatorial post to his eldest sister.)

They have also cleverly reinvented themselves from social pariahs after their patriarch’s disgraceful fall from power to celebrities once more in high society’s exclusive circles.

How the political heirs of the dictator have achieved this comeback has also much to do with the way the historical judgement rendered by the “people power” uprising has been mangled beyond recognition over the past thirty years.

The ruling elite in Philippine society have presided over the continuing distortion of what EDSA People Power was all about, what were the forces that acted and for whose interests, and what was the eventual outcome. With succeeding regimes having failed to deliver on the promise of deep-going economic, social and political reforms, historical revisionism has become the order of the day.

The over-arching myth of EDSA “People Power” is its supposed restoration of democracy with the ouster of an authoritarian order. In truth only the trappings of elite or bourgeoise democracy were restored: a Congress in the grip of political dynasties; periodic elite-dominated electoral exercises; a judiciary captured by entrenched vested interests; and the mass media owned and controlled by the elite as well.

The ruling classes of big landlords, the comprador bourgeoisie and bureaucrat capitalists remain firmly in power. What took place was a mere changing of the guards with a different faction of the ruling classes taking power by riding on the wave of the anti-dictatorship movement.

There has been no genuine land reform. The Cory Aquino and all post-EDSA regimes have persisted in their blind submission to IMF-World Bank economic policy impositions such as honoring all debts of the Marcos regime; an export-oriented, import-dependent economic model antagonistic to national industrialization; trade liberalization, privatization and deregulation; wage freeze and other neoliberal economic policies that further entrench poverty, backwardness and inequality.

Subservience to US dictates with regard to US military bases and continuing US military presence in the country has defined all the US-backed regimes after Marcos.

US-designed and directed counterinsurgency (COIN) programs were serially implemented resulting in bloody human rights records for every regime that came to power. Peace negotiations with armed revolutionary movements were dovetailed and subsumed to the objectives of COIN programs.

Graft and corruption continued unabated with a different faction of the ruling classes controlling and benefitting from the loot-taking as they took turns occupying Malacañang Palace.

The restoration-of-democracy myth was coupled with the myth that EDSA People Power was a “peaceful revolution”. In truth, there was no revolution as there was no fundamental change of the political and social system to the satisfaction of the people.

What was EDSA “People Power” in actuality? First and foremost, it was an unarmed people’s uprising that brought down the hated Marcos dictatorship. It was marked by the spontaneous outpouring of the people into the streets demanding the ouster of Marcos.

But “people power” was passed off as merely the massing-up of people spontaneously responding to the call of Cardinal Sin to support the Enrile-Ramos mutinous forces. They had been galvanized by the experience of the fraud-ridden snap presidential elections that stole victory from Corazon Aquino.

The objective of the emphasis on the unorganized mass of people is to play down the role of people’s organizations that had initiated and sustained anti-dictatorship struggles throughout the dark years. The purpose, then and now, is to airbrush progressive and revolutionary forces from the historical account of the uprising itself.

EDSA “People Power” was even mystified as a “miracle of prayers“. This attempt at obscurantism was propagated by the same leaders of the Catholic Church who had given their imprimatur to martial rule and only belatedly espoused “critical collaboration” when the people’s resistance to its brutality and criminality grew and intensified.

Second, EDSA “People Power” was a stand-off between two armed camps, that of Marcos-Ver and Enrile-Ramos. The US and the anti-Marcos reactionaries as well as the organized progressive forces and the spontaneous masses occupied the gap between the two armed camps.

Violent confrontation between the two could break out any moment so it is misleading to describe it as a “peaceful” phenomenon. Only US intervention and the growing numbers of people on the EDSA highway fronting Camp Crame prevented the Marcos-Ver camp from aggressively attacking the Enrile-Ramos camp.

The role of the Enrile-RAM-engineered coup d’etat has also been overplayed. It actually failed but it triggered an open split in the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and Philippine Constabulary (the precursor of the Philippine National Police). Subsequently, the myth of a “reformed AFP” was peddled to cover up the AFP’s fascist character and the grave human rights violations by the leading personalities in RAM such as then Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile and his aide, then Col. Greg “Gringo” Honasan.

In sum, EDSA “People Power” was the confluence of diametrically opposed forces — progressive and anti-progressive — against Marcos. Nonetheless the balance of power overwhelmingly favored the latter.

The US and the reactionary classes would determine the final outcome, the take-over by Corazon Aquino, a member of the ruling elite and a US marionette, as the chief executive officer of a political system dedicated to preserving and strengthening the status quo. #

Next week: The true legacy of EDSA People Power

Published by Business World

15 February 2016

STREETWISE: Digging deeper into the SSS pension hike by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsSpeaker Feliciano R. Belmonte, Jr. justified the abrupt adjournment of Congress last Wednesday by saying he didn’t want to embarrass President Benigno S. C. Aquino III with the prospect of a move to override the presidential veto on the SSS pension hike. Not that Rep. Neri J. Colmenares, who was leading the effort to get two thirds of the House of Representatives to sign his override resolution, already had the numbers. But Mr. Belmonte apparently was not confident he could muster the vote to defeat the resolution either.

The hurried adjournment in order to prevent even a debate and much more a vote was totally unjustified. There was a quorum, there was time. Not a few of the affected citizens were present to witness their representatives’ action in their behalf. But the house leadership went to the extent of turning off the microphone while Rep. Colmenares was in the middle of arguing for a discussion and vote.

These “people’s representatives” were caught in a dilemma.

To vote to override Aquino’s veto would likely mean reduced access to Malacanang’s largesse for the coming 2016 elections. To vote against the override, in effect to vote against the pension increase, would expose them as uncaring for the plight of SSS pensioners, spineless in the face of Malacanang pressure, and as the unprincipled, opportunist, and elitist bunch of bureaucrat capitalists they really were.

That is the rotten politics of it.

But what of the economics?

Is it true that the SSS pension bill was not well thought out, that the bill sponsors and the entire Congress merely wanted to pander to what is popular in the season of elections, that they took little regard of its supposed dire effect on the SSS fund life?

For the record, Colmenares filed the bill in 2011 and it passed through the gauntlet of the congressional mill until approved in 2015. SSS top brass had all the time and the opportunity to argue their opposition to the pension increase but they failed to convince Congress. Malacanang had the time, opportunity and clout over its congressional allies to kill the bill but it didn’t.

A 4-billion deficit per year was projected with a 56-billion peso additional cost to the fund. Fund life would be reduced to 13 years from 2015 if — a big if — nothing was done to improve collections, plug leaks, raise income on idle assets, and improve the performance of investible funds.

Worse comes to worst, the national government could appropriate the necessary funds to subsidize SSS expenses in accordance with the SSS Act of 1997. Even increasing member contributions could be considered once it has been demonstrated that SSS significantly improved its services and benefits.

The long and short of it is that the SSS can actually afford the pension hike. It is a matter of priorities; a matter of political will. Clearly the Aquino administration does not consider throwing a lifeline to 2.2 million elderly SSS members a priority. Neither does it have the political will to cut corruption, bureaucratic wastage and inefficiency in the SSS itself.

Talk about inclusive growth under the Aquino administration is a lot of hot air when SSS executives are given “performance” bonuses but its members cannot partake of the gains in its investment portfolio.

The good thing about the heated debate on the P2000-peso SSS pension hike is that many people, not just senior citizens, have begun to ask questions about what ails the country’s social security system, not just the SSS but also the GSIS, and what deep-going reforms are in order.

Progressive think-tank IBON Foundation has come up with very strong arguments backed by hard data to convince us that “social insecurity” actually hounds majority of Filipinos up until their twilight years.

For one, out of 7.8 million senior citizens, IBON estimates that at least two-thirds or over 5.1 million are poor. (IBON uses a poverty threshold of Php125 per day or Php3,800 monthly whereas the Philippine Statistics Authority officially uses an unrealistic poverty threshold of just Php52 per day or some Php1,582 monthly.)

Moreover, six out of ten (57%) elderly Filipinos, or some 4.5 million, don’t receive any pension at all.

If we include those who receive pensions below a reasonable poverty threshold, this would mean almost 97% of elderly Filipinos, or around 7.5 million, cannot afford to live decently much less be able to buy costly maintenance medicines for their various illnesses.

According to IBON, “Coverage is poor because the country’s main pension schemes are designed as an individualistic mechanism more than real social security. The SSS and GSIS are contributory schemes that only cover their members, whose membership depends on member contributions, and whose level of benefit depends on the level of member contributions…But the problems of basing pensions on regular work-based contributions in the Philippine context of so much joblessness and pervasive irregular and low-paying employment are clear.”

The unemployed will certainly not be able to make any significant contributions. But not even those employed are assured of becoming active and qualified SSS members. IBON estimates six out of ten of total employed (58%) are non-regular workers, agency-hired workers, or in the informal sector with at best erratic ability to pay contributions. The problem gets worse with the rising practice of contractualization wherein workers have no security of tenure and are simply hired and rehired every six months.

IBON concludes that the only way forward is for government “to confront Philippine underdevelopment realities head-on and aim for a non-contributory tax-financed universal social security system…(S)ociety, through the government, should be assuming primary responsibility for the security of its most vulnerable citizens including the elderly. Contributory member-financed schemes such as SSS and GSIS should just be complementary measures to a central scheme designed to reach the majority of Filipinos.”

Unfortunately, so long as the neoliberal economic doctrine has a stranglehold over the mindset of our country’s political leaders, government economic policies will continue to eschew this approach to overhauling the social security system.

The so-called “free market” means every man for himself; government intervention to promote social equity and social justice are anathema; even social safety nets for the most vulnerable in society are considered burdensome and unsustainable.

The struggles of senior citizens and their families for a meaningful increase in SSS pensions are giving them valuable lessons in life. Who are with them and who are against them and why. The nature of reactionary politics in an elite-dominated society such as Philippine society. And most important of all, that meaningful changes can only take place when the exploited and oppressed unite and take matters into their own hands.

Senior citizen power is also “people power”; once unleashed, it will find its mark. #

Published in Business World

8 February 2016

STREETWISE: SSS pension hike — it’s a class thing by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsStreetwise

I waited to hear the views of a friend, a former SSS top executive who sought a meeting with Rep. Neri Colmenares, original sponsor of the bill that seeks to raise the Social Security System (SSS) monthly pension for more than 2 million retirees by P2000. I wanted to balance out my thinking on the issue even though I had read and heard almost all there was to hear on both sides of the argument.

I wanted to give this person the benefit of the doubt since I know him to be an upright person, hardworking, a top professional in the private sector before being recruited into government service, and having come from humble beginnings. Unfortunately the more he expounded on the basic position of current SSS executives, on which basis Pres. BS Aquino vetoed the bill, the more I became unconvinced of the merit, nay soundness, of the presidential veto.

While acknowledging that the SSS fund is a social fund meant to serve the needs of its members, the former official tried to convince us that people expected too much from the fund, that the contributions were way too small while the services it was giving out were costing a lot. Ergo the basic solution is to increase the members’ contributions. In the meantime, there could be no increases in benefits that would only shorten the life of the fund.

He acknowledged, however that increasing contributions is easier said than done. The convincing would have to come in the form of more efficient and substantial services.

Now when one considers that the SSS was listed recently by the Civil Service Commission as one of the top three government agencies that they received complaints about in terms of services, doesn’t the SSS indeed have a lot of convincing to do?

Wouldn’t a reasonable increase in pensions serve as a strong signal that the agency was willing to work hard to be able to give members a decent pension when they retire?

When asked about plugging the leaks in the system like the billions of contributions collected but unremitted by employers, the former official lamented how difficult it is to do this, that SSS lacks personnel and resources.

So how can SSS convince its members that they need to give more when what they are already contributing is not collected properly by SSS. (Or as one struggling entrepreneur counter-lamented, it takes SSS forever to officially tally contributions in their data base from the time the payments are deposited in receiving banks. In the meantime their employees cannot take out any loans and vent their ire on their employers!)

About the touted sterling performance of the SSS in terms of fund management under the stewardship of SSS President De Quiros, my friend intimated that there were SSS properties that were not sold during earlier administrations in order to have higher returns with the property boom in certain areas of Metro Manila. This certainly didn’t seem to take such a financial genius to figure out; that it was quite a matter of waiting for a better price.

In the meantime, .isn’t it unconscionable for SSS executives to give themselves such fat bonuses on the ground that they made the fund grow through their supposedly astute handling of SSS investible funds when they refuse to let the ordinary members share in some of that purported growth. On this point my friend couldn’t help but nod in agreement.

Rep. Colmenares came quite prepared for the one-on-one discussion bringing with him documents that the SSS had submitted to congressional hearings. He had the facts and figures at his finger tips. He questioned the sudden jump in the projected fund deficit to 16-26 billion pesos when SSS officials had stated under oath in congressional hearings this would amount to only 4 billion pesos.

Congress had passed Colmenares’ bill unanimously having taken into account the 4 billion deficit and the ways by which the SSS could cover this by introducing needed reforms within the next five years, including improvement in collections and lessening administrative inefficiencies and costs. And if, despite all these internal reform measures the deficit remained, government is mandated to shore up the fund by means of a direct subsidy.

Indeed, if government can subsidize a dole-out program such as the Conditional Cash Transfer worth 62 billion pesos, why can’t it provide a safety net for working people who are doing their share not only in contributing to the economy but to their own social security fund .

It has also been pointed out by various quarters that with the Aquino administration’s boast of a 268 billion peso reduction in the government’s budget deficit, it has more than enough leeway to back up the P56B for the pension hike plus the alleged projected P16-26B SSS deficit.

How convenient — or deceptive as the case may be — for SSS executives to belatedly come up with such a humongous figure of 16-26 billion pesos in fund deficit that would purportedly run the SSS fund to the ground in 13 years.

This report apparently stunned and scared Pres. Aquino — during the four years the bill was being deliberated apparently he took no notice of it and its supposed dire implications — into action. He obviously took the SSS executives’ word hook, line and sinker, enough for him to issue the politically unpalatable veto

Thereupon the entire Malacanang propaganda machinery was made to work overtime to spread the scare to the rest of the public, most especially to SSS non-pensioners who the Aquino administration wants to dupe into believing that there will be nothing left for them when it is their turn to retire.

Big business honchos, top-caliber professionals in the financial sector and neoliberal academics and pundits who think government subsidy is anathema to the “free market” have swallowed the bankruptcy scare hook, line and sinker too. One wonders why they have chosen to suspend their usual sharp analytical abilities in this instance.

The reason is not hard to fathom. They regard the SSS not as a social fund but as a huge capital fund that one necessarily subjects to actuarial studies regarding its projected life.

Thus the point is reduced to how to ensure that more comes in than what goes out.

Yes, even as hundreds of billions of the SSS fund are a plump source of income for a train of fund managers, stock brokers, investment bankers, accounting firms and the like.

In the final analysis, the two sides to this issue amounts to a class divide. The less in life can’t understand the reason for the presidential veto. Those who can nonchalantly spend 2000 pesos and more on dinner-for-two at a fancy restaurant can’t appreciate the clamor for a pension increase in their lifetime.

Published in Business World

1 February 2016

STREETWISE: The Colombian peace process — a model for the Philippines? by Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsStreetwise

Ask a Filipino nowadays what he or she knows about Colombia and chances are the reply will be about how the reigning Miss Universe, the Philippines’ Pia Alonzo Wurztbach, almost lost her crown to Miss Colombia, Ariadna Gutiérrez, after the emcee mistakenly announced the Colombian beauty to be the winner.

However there is much much more going on in this Latin American country of 48 million people. Of major significance nationally and regionally is the more than three-year-old peace negotiations between the Colombian government led by President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) to resolve five decades of armed conflict with the largest of several guerrilla groups operating inside the country. A negotiated political settlement is aimed for by March of this year.

The Royal Norwegian Government (RNG) has been playing a pivotal role, together with the Cuban government, as facilitator in the Colombian peace negotiations. (The RNG is also third party facilitator in the peace talks between the Philippine government or GPH and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines or NDFP). Recently, the RNG brought its special envoy for the Colombian peace process, Mr. Dag Nylander, to Manila for him to share his experiences and to have a candid discussion with different groups and personalities here regarding the stalled GPH-NDFP peace negotiations.

Nylander shared not just information but insight into what he sees as the key elements that have contributed to the big progress in the peace negotiations in Colombia. He highlighted three of them: the “commitment” of the two sides to the peace process; the “inclusivity” of the process; and lastly, the “involvement” of international third parties.

Nylander said the Santos government clearly demonstrated its seriousness about entering into talks with FARC by no longer categorizing the revolutionary organization as a “narco-terrorist” (i.e. a “terrorist” group that engages in drug trafficking to fund its operations and gain adherents) in contrast to its predecessor, the Uribe government. President Santos, who was previously defense minister and a hardliner in dealing with FARC, implicitly recognized the latter as a political group with political goals and “historical reasons” for its existence. Nylander underscored, however, that Santos never “legitimized” FARC’s armed struggle against the government.

For its part, Nylander said FARC clearly took a “risky” decision of entering into peace talks with its avowed enemy because it was convinced that there was a possibility for a “strategic solution”. He said FARC concluded that they were being “taken seriously by their opponent”. Considering the extremely bloody US-backed counterinsurgency programs implemented by a series of Colombian governments that have led to hundreds of thousands of civilians and tens of thousands of its members killed, FARC must have had plenty of good reasons, internal and external, to agree to the talks. Nylander mentioned the strong push for talks by Cuban leader Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, both of whom were considered staunch supporters of FARC.

Over six months of negotiations, a framework agreement was concluded that laid as the objective not just the end to the armed conflict but the resolution of its underlying causes. FARC did not get all of its proposed agenda included but settled on four out of five that was mutually agreed upon: land reform, political participation, illegal drugs trade, victim compensation and justice, and end of conflict.

Just last January 15, the two parties inked a particularly thorny “transitional justice” agreement that had to do with of justice and reparations to victims of one of the world’s longest-running conflicts. This agreement held that FARC combatants and members would not be jailed for their “crimes” as rebels so long as they “confessed” to these through a tribunal that would be set up. They would instead make “reparations” in some other way, eg doing landmine clearing in designated areas.

Interestingly, a bilateral ceasefire was not a precondition to the start of the peace talks. It was the FARC that wanted a long-term ceasefire even before the negotiations were completed but the government has so far refused arguing that FARC would use the reprieve to consolidate itself. When FARC declared a unilateral ceasefire, government was eventually forced to reciprocate due to domestic and international pressure. It stopped its aerial bombardments of FARC-controlled areas even as other military operations continued.

Constitutional amendments to accommodate the terms of the final peace settlement are not anathema as far as the Colombian government is concerned. According to Nylander many adjustments are already being anticipated and prepared for to avoid legal and constitutional booby traps that could ensnare and sabotage the negotiations.

Even the language being used is meant to avoid the perception that FARC is negotiating its own surrender. The demobilization of the revolutionary army is called “laying weapons aside” and up for negotiations still is whether FARC’s arms will be turned over to the government (that FARC still distrusts) or to an international third party and what protection will there be for its members once they are no longer armed.

The sharing with Nylander certainly spurred this writer and peace advocate to study the Colombian peace process more closely. Will it result in far-reaching socioeconomic and political reforms requisite to the forging of a just and lasting peace or will its outcome be the pacification and cooptation of a formidable revolutionary organization that has sustained its armed struggle for more than half a century.

For its part, the GPH-NDFP peace talks are currently plagued by a clear lack of commitment primarily from the Aquino government . The Aquino administration has shown its utter lack of political will to persist in the negotiations in the wake of twists and turns inherent in the process and to abide by inked bilateral agreements whether these be the framework agreement (The Hague Joint Declaration), safety and immunity guarantees (JASIG), or even just confidence-building measures (release of a certain number of political prisoners especially for humanitarian reasons such as the elderly or the sick.)

Aquino’s adviser on the peace process, Sec. Teresita “Ging” Deles, and the GPH chief negotiator, Atty. Alex Padilla, have proven themselves as plain obstructionists by virtue of their ideologically-driven hard-line positions and propensity to throw a monkey wrench into the process; their lack of openness and creativity in working out solutions to impasses or even just sticky negotiation points; and their track record of torpedoing any attempts by concerned groups or individuals to restart the talks that have been virtually deadlocked for almost the entire Aquino presidency.

President Aquino should have fired both Deles and Padilla long ago for being incompetent non-performing government officials. That he has not done so places the onus of frozen GPH-NDFP peace negotiations squarely on his shoulders. Eof

Published in Business World

18 January 2016

Streetwise: Lessons learned By Carol Pagaduan-Araullo

/in News, Opinion/Analysis /by Kodao ProductionsStreetwise

Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City is not called the “killer highway” for nothing. It is notorious for vehicular accidents involving all manner of wheeled conveyances: speeding buses and jeepneys whose breaks invariably “fail”; tricycles that aren’t even supposed to be plying this major thoroughfare; sleek late-model sedans and SUVs whose drivers can’t resist going at top speed given the avenue’s 10-lane width; and, oh yes, motorcycles weaving in and out of traffic to their and other motorists’ peril.

Commonwealth Avenue finally got to us last weekend scaring the living daylights from me.

There we were cruising at 40 kph in the middle lane when a Tamaraw Fx van (reconfigured to have an open bed like a pick-up) suddenly came at us from the inner lane. I saw bodies fly into the air and fall into our path. The driver slammed the breaks and mercifully kept our pick-up from running over the people underneath. But the tailgate of the Tamaraw Fx opened and hit our pick-up before falling on its side. The next thing I heard were the wailing of women passengers of the Fx as they piled out of their vehicle and saw their bloodied companions sprawled on the road.

It was only when the rescue teams had extricated the two men from underneath our pick-up and brought them to the emergency room of the nearby hospital was I able to step out into the street. (I couldn’t bear looking at what I anticipated to be a horrible scene that would be seared into my consciousness.) I then saw a black sedan in the inner lane of the avenue with its front part crushed. It apparently hit the back of the Fx sending it careening towards our direction.

There were plenty of police as well as members of rescue teams, some official and others from volunteer groups, milling around. Some of the police set up barriers and were redirecting traffic. No one approached either my husband or me to ask if we were hurt or if we saw what happened. I saw a policeman directing our driver to take their photos beside the Fx Tamaraw still lying on its side. (According to our driver, they said they needed to document that they were on the scene doing their jobs!)

Meanwhile my husband heard a policeman say that the Korean driver reeked of alcohol. He told me that the investigators on the scene had no breath analyzer. I proceeded to the ER to ask whether the hospital could check for blood alcohol levels but was told they did not have the capability. The ER nurse and resident-on-duty however noted that the Korean had “positive alcoholic breath” or “+AB” and assured me this observation would be written on his chart.

Subsequently I asked a friend in media for help in having a breath analyzer brought to the hospital. My friend informed me that they had requested the LTO to send one to the hospital but it would take time as the one in charge was still asleep! An MMDA traffic investigator who later arrived at the hospital said the instrument would be brought in from Makati. We were instructed to go to the police station so that our statements about the accident could be taken but only our driver was asked to fill up a form stating what he knew of the accident. We were not advised that we, as owners of the involved vehicle, needed to file a criminal complaint, i.e. reckless imprudence resulting to damage to property.

I did what I could to help the injured get proper treatment especially the one who lay comatose fighting for his life. After consulting a neurosurgeon friend, I urged the employer of the critically injured to have them transferred to a better equipped medical facility. We also advised the employer to have his people guard the Korean driver (who had been admitted to the hospital) to make sure he would not flee.

We counted our blessings that we were unhurt although our pick-up had sustained major damage. We went home to get much needed rest assuming the wheels of justice were turning; in particular, that the authorities investigating the accident were doing their part.

What followed next shows that victims of vehicular accidents have much more to contend with apart from the injuries and damages they sustain. Many times they are left to their own devices and are at a loss as to what to do. We only learned later in the day from a lawyer friend that to ensure the Korean driver would be made to account for causing the accident and be prevented from escaping, all the victims needed to immediately file criminal complaints. These would be subjected to an inquest proceeding wherein the fiscal would determine whether there was probable cause to immediately charge the offending party and place him under police custody.

There was an interminable wait at the police station while they finalized their report and completed the needed documents provided by the victims. (The police seemed to be acting in slow motion such that a victim quipped perhaps they needed some “lubricant” to speed things up.) Despite our repeated inquiries, the police kept telling us that we did not need to file a separate criminal complaint for the damage to our pick-up.

We proceeded to the inquest fiscal’s office at the Quezon City Hall of Justice where we endured another long wait for the fiscal-on-duty to arrive and for our turn to be heard. As hours passed (it was nearing midnight), I got more and more exasperated at the seemingly endless wait with no one advising us as to what to expect. Rather than be cheered by the Christmas lights on the city hall grounds and carols blaring from the PA system, our anxiety and feeling of oppression grew by the minute.

When our turn came before the inquest fiscal, we were surprised to learn that we were not a party to the complaint because we didn’t file a separate case. Only the charge of reckless imprudence resulting to serious physical injuries would be heard. Our own complaint would go through the usual process of preliminary investigation once we filed it meaning another long wait for the wheels of justice to turn, if these would turn at all.

At risk of being cited for impertinence by the fiscal since we had no legal standing in the case, I ventured to say that there were initial reports that the Korean driver was driving under the influence of alcohol. The fiscal flipped through the documents submitted by the police and flatly said the medico-legal certificate the police attached to their report did not mention any such finding. Another surprise!

Thus in the wee hours of the morning we hied to the hospital where the injured had been taken for emergency treatment including the Korean driver. We verified that the ER resident-on-duty who examined the Korean had written her finding of “+ AB” but since this finding was considered “subjective”, the medico-legal officer of the hospital had not included it in his certification. What would be considered “objective” findings? The results from a breath analyzer or blood alcohol levels, none which was availed of by the accident investigators. It turns out that such a crucial piece of information had been missed out, inadvertently or deliberately, we will never know.

What does this experience teach us? If you ever find yourself involved in a traffic accident that puts life and limb at risk or that results in major property damage, keep these in mind: 1) pay close attention to what the traffic police or MMDA investigators are doing and get their names and official designations; 2) consult a lawyer first chance you get and if possible, have her accompany you to help protect your interests; 3) as much as possible, work out an amicable out-of-court settlement, without surrendering your rights as an aggrieved party.

Be ready to contend with uncaring, incompetent and/or corrupt investigators; a prosecutorial system bogged down by a huge backlog of cases and fiscals who drag their feet or are quick to file depending on “considerations”; and a judicial system that will grind exceedingly slow until injustice runs its inevitable course.

No wonder many Filipinos are seduced by the prospect of extra-judicial shortcuts as the solution to rampant criminality and anarchy in the streets. But then again, that is tantamount to giving the same state agents responsible for the broken-down system to further flout the law and pave the way for all hell to finally break loose.#

Published in Business World

21 December 2015