The ill logic of rice liberalization

by Rosario Guzman/IBON Foundation

Runaway inflation has always been our economic managers’ alibi for liberalizing importation. Food always takes a beating from this short-sighted policy, as it has the single biggest weight of 36% in the average commodity basket.

Inflation reached its highest in a decade in 2018 upon the implementation of the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Law, the most comprehensive and most regressive tax reform the country has ever had. TRAIN slapped value-added taxes and excises on consumer products, including unprecedentedly on all petroleum products. It reduced income taxes, which have benefited only the rich more than the middle class and the poor, as it has ultimately rebalanced income gains with higher prices.

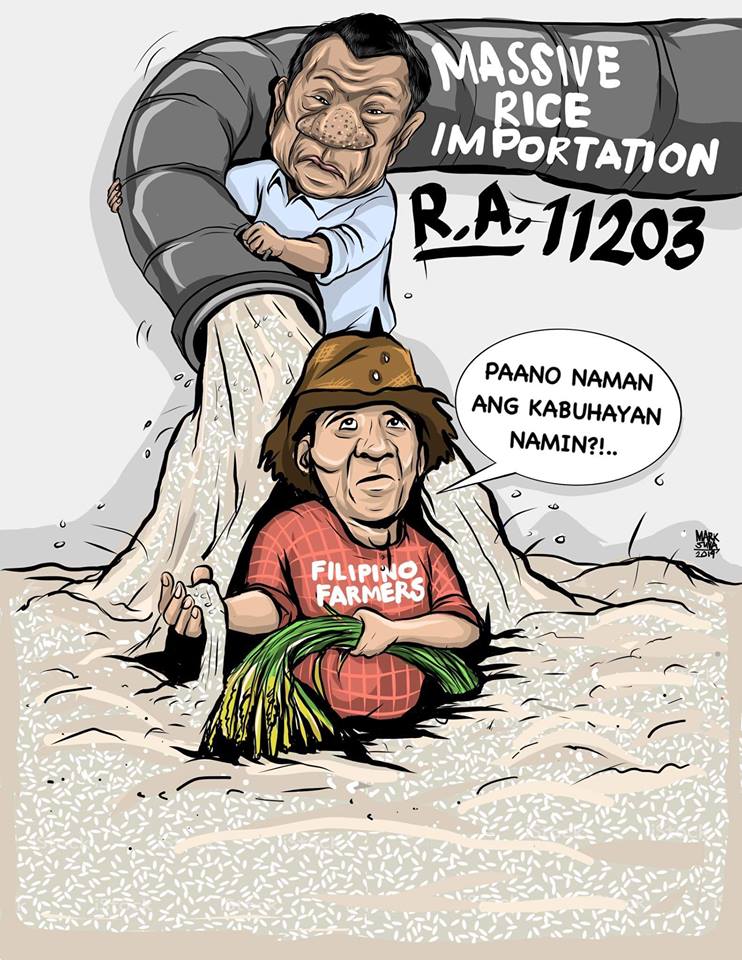

But it was still the rice’s fault, according to our economic managers, and hastily they did push for the tariffication of the quantitative restrictions on the country’s staple. Rice bears a 9.6% weight on inflation and it is an extremely socially sensitive product on the same level as diesel that TRAIN had finally taxed; thus it has to be kept under control. That is their logic for subjecting local rice to undue competition with imported rice that is far better government protected and supported.

Wrong premises

Our economic managers would later point to decreased rice retail prices, although still higher than pre-tariffication levels, to support the argument that imports liberalization indeed benefits the Filipino consumer.

It’s turning out to be a feeble argument, however, as the country would again see the highest food inflation in 27 months at the beginning of 2021, with meat and vegetables contributing the most. The apparent cause is government’s non-containment of the African swine fever epidemic in the hog subsector. But despite the obvious need for government intervention in domestic production, the official quick reaction is again liberalization, this time of pork imports.

The government has simply been pitting the welfare of local producers against that of the consumers, apparently in a principle of subordinating the interests of the few (the farmers) to the welfare of the many (the consumers). This is also wrongly premised on the Filipino consumers being concerned only with cheap commodities. Joblessness is at its worst level, while economic aid in the face of the pandemic has been meager. Majority of the Filipino consumers need to be productive first and earn decent incomes, or in the immediate be given economic relief, before they could truly benefit from lower prices. But government’s obsession with imports liberalization has only worsened the jobs crisis, loss of livelihoods, and farmers’ bankruptcy.

Denied reality

From 2018 to 2020, palay prices have gone down by an average of 19.5% for both fancy and other varieties. Palay prices are lower by a minimum of Php3.30 per kilo for other varieties, from a national average of Php20.06 to Php16.76 per kilo. Nine of the 17 regions have even lower palay prices than the national average. These are based on official statistics.

Field studies conducted on the first year of the rice tariffication law by Bantay Bigas, a nationwide network of rice advocates, showed farmgate prices going down to as low as Php10-15 per kilo. Palay prices in the range of Php10-14 per kilo were noted in the country’s rice bowls – Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, Bulacan, Pangasinan, Isabela, Ilocos Sur, Mindoro, Bicol, Negros Occidental, Capiz, and Antique. Palay prices in the range of Php11-15 per kilo were seen in Agusan del Sur, Davao de Oro, Davao del Norte, South Cotabato, North Cotabato, Lanao del Norte, and Caraga. Bantay Bigas noted that palay prices continuously declined in four consecutive cropping seasons right after the passage of the rice tariffication law.

Value of palay production went down from Php385 billion in 2018 to Php318.8 billion in 2020 despite a slight increase of 229,000 metric tons (MT) in production volume at 19.3 million MT in 2020. If the average farmgate price of Php20.06 before rice tariffication was maintained, production value would be more or less at the level of Php387 billion – thus a visible loss of Php68.3 billion in the last two years, or Php32,523 for each rice farmer.

These are based on official figures. Bantay Bigas noted that farmers in Zaragoza, Nueva Ecija lost Php20,000 to Php35,000 per hectare in 2019, as farmgate prices dropped to Php14 per kilo during the dry season and Php10-13 per kilo during the wet season. Farmers in Barangay Carmen in the same municipality have mortgaged about 40% of their rice lands or an estimated 80 hectares due to depressed farmgate prices. In Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija, some rice lands near the highways were already sold at Php1 million per hectare.

In 2019, rice farmers’ net income per hectare decreased by 32% in the dry season, by 47% in the wet season, and by 38% on the average as compared to figures in 2018, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. This translated to substantially lower profitability ratio for the farmers. For every peso the rice farmer spent on one hectare, his profit declined in 2019 from 73 centavos to 53 centavos in the dry season, from 63 to 36 in the wet season, and on the average from 73 centavos to 47 centavos.

The average net income of Php21,324 in 2019 translated to Php236.93 per day in a 90-day cropping season, down from 2018’s Php34,111 or Php379.01 a day. The farmer lost Php142.08 income per day, which was way bigger than the Php4.65 per day that his family supposedly gained from cheaper rice. (Regular milled rice was reportedly cheaper by Php2.86 per kilo in 2019. The daily average per capita rice consumption is 325.5 grams or 0.3255 kilogram. Thus, 0.3255 kilogram x 5 family members x Php2.86 = Php4.65)

These are official figures. We are not even talking about rice farmers who incurred net losses.

Also incidentally, the Php236.93 income per day recorded in 2019 was short of the already incredibly low official poverty threshold of Php354 per day for a family of five. It was not even enough for the official family food threshold of Php248. The reality is undeniable: the country’s rice producers live in acute poverty and hunger, and rice liberalization is directly responsible for this irony.

The bigger picture

The rice tariffication law purports to offset these losses by allocating the tariff revenues to support farmers. We do not need to go into detail about how these are not enough or at worst tokenistic. We only need to see the trend of government’s agricultural support to conclude that the Duterte administration has put the sector aside in favor of other hollow and counter-productive budget items, including its infrastructure agenda.

The budget for agriculture in 2021 is only Php110.16 billion, merely 2.2% of the national budget. This has diminished further from the 2019 share of 2.7%, which is apparently already the largest under the Duterte administration. Including the budget for agrarian reform, the annual average allocation in 2017-2020 is only 3.6% of the national budget, the lowest in 21 years. This still got smaller at 3.2% in 2021.

The country’s rice self-sufficiency ratio has significantly gone down from 93.4% in 2017 to only 79.8% by 2019. Such increased import dependence is not even justified anymore by the goal of curbing inflation nor by inadequate supply. It is but a formed habit from chronically neglecting domestic production. To illustrate, despite the hyped increase in production volume in 2020 and even at harvest time, the Duterte government approved the importation of 300,000 MT. The pandemic has apparently prompted exporters such as Vietnam and Thailand to prioritize their domestic consumption, triggering already ingrained insecurity among importers such as the Philippines.

Also totally negating the inflation argument now is the fact that Vietnam and China have already started buying rice from India due to increased local prices. This could precipitate another fast rice inflation in the narrow global market, on which the Philippines has unduly relied at the expense of its own direct producers.

This brings us back to the bigger picture – that the farmers’ struggle for the reversal of rice liberalization and for more responsible state intervention is not just about themselves but the more meaningful future of food security and national development. #

= = = = = = =

(A contribution to the virtual forum “Rice Tariffication Law: Two Years After” sponsored by the College of Economic Management, University of the Philippines Los Baños, 22 June 2021)