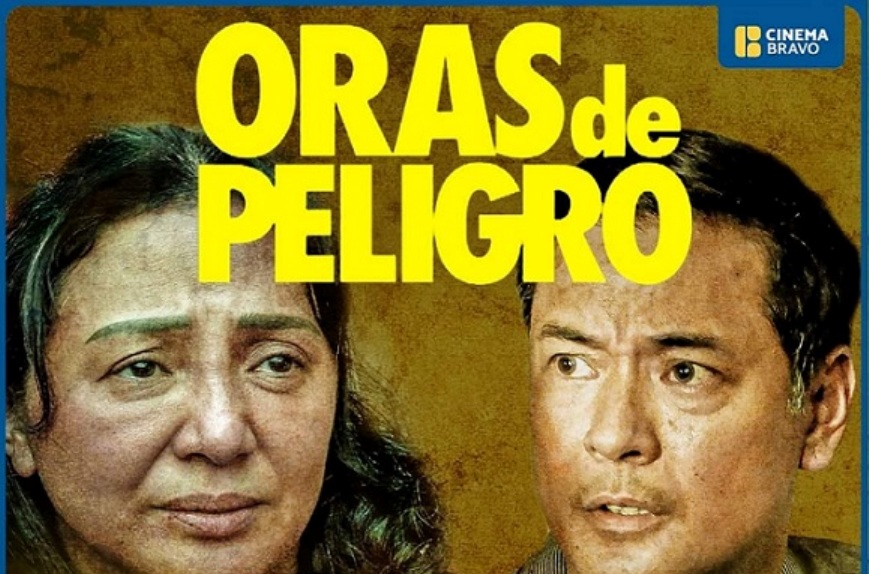

ORAS DE PELIGRO FILM REVIEW: What People Power Really Looks Like

By L. S. Mendizabal

4 out of 5 stars

Last February 25, Filipinos commemorated the 37th anniversary of the EDSA People Power Uprising—a series of nationwide public protests in 1986 that culminated in the ouster of former president, Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., after 21 years of dictatorial rule. On the same day, his son and namesake, and current president, sent a wreath of flowers to the People Power Monument, calling for “peace, unity and reconciliation.” Meanwhile, his sister, Senator Imee Marcos said she “could never stomach celebrating” (the anniversary).

What is there to make peace with, or celebrate anyway? None of the Marcoses have been held accountable for the billions of pesos they stole from the people, or the tens of thousands of Filipinos they had killed extrajudicially, tortured, “disappeared” and incarcerated illegally.

And yet, Joel Lamangan’s latest offering with Bagong Siklab Productions’ Oras de Peligro, has an optimistic air about it that is difficult to ignore as it pierces through the series of tragedies which befalls its main protagonists. One familiar with Lamangan’s filmography knows all too well that serial tragedies are kind of his thing. Never subtle, rarely complex and almost always campy, it is easy to imagine any Lamangan movie reworked as a play, or stretched out into a teleserye with little revision. This has, time and again, been Lamangan’s undeniable cinematic mass appeal. And Oras is no different. His vision, married with that of Bonifacio Ilagan and Eric Ramos’s writing, makes the film a compelling watch for the contemporary mass audience.

Oras is, at its core, a family drama. Dario Marianas (Allen Dizon) is a farmer’s son who has found work as a jeepney driver in the city and built a family with a housemaid, Beatriz (Cherry Pie Picache). They earn barely enough to be able to send their daughter, Nerissa (Therese Malvar), to college, while their older son, Jimmy (Dave Bornea), applies for odd jobs anywhere he can.

Set in the wake of the botched 1986 snap elections, the story begins with widespread mass unrest. Members of the ruling class and their pawns, including the armed forces, are extremely divided as well. The Marianases, too wrapped up in their domestic problems, cannot be bothered with political activities, let alone political discussions. “’Wag na tayo sumali sa mga ganyan, kumayod na lang tayo nang kumayod (“Let us not participate in such things, let us work and nothing more)!” Beatriz passionately shuts down the slightest suggestion of social action from Dario.

Lamentably yet inevitably, crime, poverty and fascism are a reality that outweighs the family’s simple everyday resolve to put food on the table. A single day is about to change their lives when Jimmy unwittingly gets involved in a labor union strike, and Dario in a holdup incident aboard his jeepney. Both events lead to a violent clash with elements of the then Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police’s Metropolitan Command (MetroCom). To keep the criminals’ loot for themselves, the cops execute Dario. Only one passenger (Elora Españo) witnesses his murder. When Beatriz is summoned by the MetroCom, she does not believe what they tell her about the cause and nature of Dario’s sudden death. Still fighting off shock and tears, she threatens the cops with a civil complaint even though legal aid is the last thing they can afford on top of the funeral and burial costs. She sounds uncertain and meek, bordering on weak, but fearless nonetheless. The Marianases, despite being largely passive individuals at first, are instantly treated by the cops as enemies of the state.

Picache delivers a riveting performance, weaving in complex emotions into the simplest of lines. The overly dramatic music synchronized with her every howl and whimper almost ruins it in my opinion. In contrast, there is a perfect scene in the movie that is beautifully scored with Becky Demetillo-Abraham’s emotional interpretation of the film’s theme song of the same title: Dario’s father, peasant leader, Ka Elyong (Nanding Josef), quietly arrives at his son’s wake. Eyes brimming with tears, he is evidently shaken by the sight of Dario’s casket. Before him, a dove takes off from the ground. Its wings, flapping swiftly, miss his cheek by an inch or two.

Lamangan plays with the genre, juxtaposing the trials and tribulations of the Marianas family against old footages and shots of news clippings from the time. He also inserts a few humorous moments here and there—the most memorable is when Jimmy leaves a mortuary called “Badoy Funeral Services”—to the audience’s delight. Not all changes in narrative tone work to the film’s favor, though. For instance, in a heated argument near a workers’ strike, Jimmy and his friend Yix debate on the bigger enemy, Marcos the dictator or the capitalist, both of which are condemned by the workers on their placards. In another scene, student activists discuss the worsening rupture within the ruling class in the country, concluding that a “revolution” entails a total overhaul of the system, that the militant Left must not act hastily without first studying and assessing the situation with care and that this brewing People Power Revolution, however incomplete and insufficient, is to be cherished as the people’s initiative (“Atin ang rebolusyon!”).

There are quite a number of scenes like these whose intentions I wholeheartedly appreciate and agree with, but which could benefit from more showing rather than telling. Unfortunately, there is too much clunky dialogue and a dearth of nuance. This may be attributed partly to the low budget Oras has had to operate on, but mostly to a dogged desire to say everything all at once—not unlike an elder on his deathbed rushing his last words, worried that his successors might easily find it in their hearts to forgive and forget the trespasses committed against their ancestors. Seen this way, I somewhat understand the inelegant impulse with which Oras facilitates its discourse. After all, it yearns to speak to a nation twice duped by the Marcoses.

This yearning makes Oras an important film if only for the pursuit of Truth in an age when anything and everything can be true as long as the truth-teller is in power. Not only does it retell the events surrounding the first People Power from the masses’ point of view; it also reframes the common misconception about the people’s revolution—that placing flowers and yellow ribbons on soldiers’ guns or that millions of Filipinos clad in all-pink gathering to celebrate a woman leader will have to do (no matter how defiant that must have seemed in a post-Duterte, post-COVID Philippines!), and that it can be bloodless.

With its imperfect execution yet assuredly bold narrative, and even bolder ending which foregrounds the united people’s front over individual players other mainstream fiction and nonfiction films may tend to spotlight—the likes of Benigno and Corazon Aquino, Gringo Honasan, Juan Ponce Enrile, Fidel Ramos, etc.—Oras offers hope in the endless possibilities it presents when the passive bystander becomes an active agent of change, when students, doctors, rich employers and even high-ranking officials of the armed forces join the most oppressed and marginalized, the farmers and the workers (the Marianases, essentially), in their fight for justice and liberation. Oras takes comfort, and likewise gives comfort, in the fact that such are not merely possibilities but are, in reality, part of Philippine history.

It is not surprising then that the current administration has all but promoted social media content, YouTube vlogs and feature films that tell a dramatically different story. It is not surprising, either, that Darryl Yap’s Martyr or Murderer has since been moved from its original release date to the same date as Oras. There is an actual ongoing race of opposite interpretations of history. The Marcoses may have the upper hand of holding greater political power for now, but the people still possess their memory. Then again, memory, even in its most preserved state, can only do so much. A monument, no matter its size and significance to a people’s history, can only mean so much. And it certainly does not mean squat to a thiefdom even when they come with a wreath of white flowers and a message of peace.

In the open forum following the film’s invitational premiere at Cine Adarna in the University of the Philippines on February 24, Mila Aguilar, a poet and Martial Law survivor, tearfully shared how much she loved the movie and how, if only for an hour and 44 minutes, it made her forget the pain of being imprisoned. Indeed, Oras is Lamangan’s love letter to the Marianases and Milas, and all the other victims and survivors of the first Marcos regime. No one can ever take away whatever catharsis and solace this film may provide them.

As much as it comforts the afflicted, however, Oras also poses a challenge not just to the second Marcos regime, but to today’s young filmmakers, cultural workers and artists to create something out of the memories of our elders so that the lives they have lived and lessons they have painstakingly learned will not be in vain. We owe it to yesterday’s and tomorrow’s dreamers and freedom fighters to continue retelling our people’s stories, engaging in progressive discourses and actively participating in the relentless fight for Truth in the midst of massive disinformation, and in the years, arguably still, of living dangerously.

There is a remarkable level of innocence and earnest optimism to Oras as it remains steadfast in the fight for social change amidst a dominant atmosphere of jadedness and despair among Filipinos, especially in the aftermath of the May 2022 elections. Despite all that Lamangan has gone through, including his triple bypass surgery in December, and in spite of the anonymous death threat received by Ilagan recently, they have managed to push this courageous, little film to be shown in big cinemas in the country in the era of the Marcoses’ active efforts to distort history, no less. Far from perfection, Oras deserves all the credit for retelling and reimagining a true people’s revolt, something very few films dare hint at. It has a place in online archives, in schools, in the streets and in the countryside where history is not only remembered and retold, but more importantly, where the people make history. Do your loved ones a favor and bring them to see Oras de Peligro, now showing and lighting the signal fire of the anti-fascist historical revisionist discourse at cinemas nationwide.#