More than a tale of two bishops

The religious in one of Asia’s predominantly Christian countries, the Philippines, may be among the most persecuted in the world.

By Raymund B. Villanueva

The moment may have been the most profound display of sadness that Filipino Roman Catholic Bishop Gerardo Alminaza had shown in public yet. At a peace forum in Manila last April, the usually cheerful prelate’s voice broke mid-speech. It took him several seconds to regain his composure, but he was still teary-eyed as he said, “I recently experienced a barrage of red-tagging, after I put out a Lenten statement with Pilgrims for Peace.”

Alminaza is known for his sermons and statements that show his iron-clad resolve to bring peace to his beleaguered flock in Negros Island in central Philippines. But being red-tagged in the Philippines can be deadly.

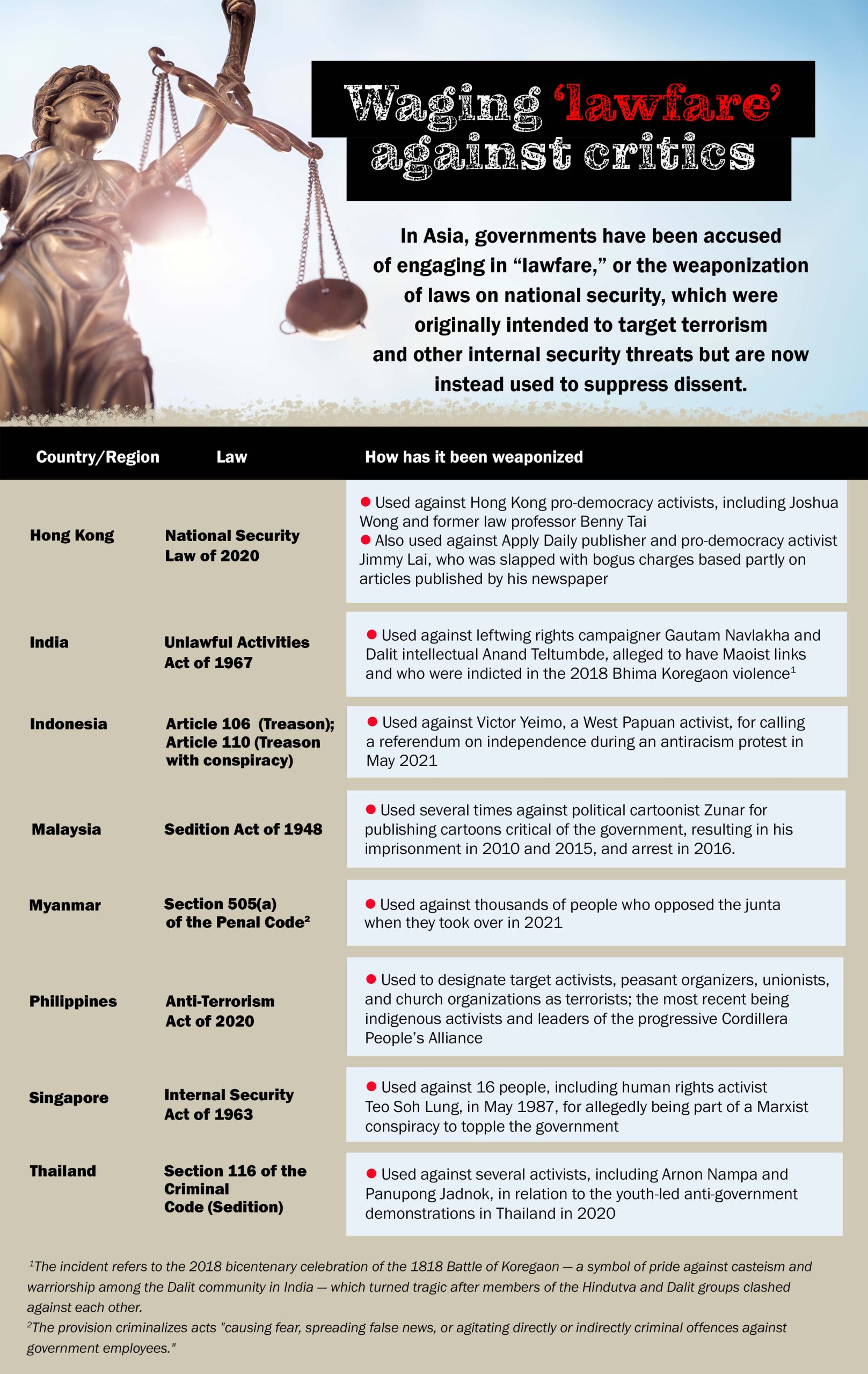

The practice is defined as a malicious blacklisting of individuals or organizations as communists or terrorists, or both. The Philippine government has admitted on various occasions that it approves of red-tagging despite calls from local and international rights advocates for it to be stopped. In his speech before the U.N. Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in Geneva in October 2022, current justice secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla said, “It’s par for the course.”

“If you can dish it out, you should be able to take it,” Remulla told the 136th session of the Council, which questioned the Philippine government about red-tagging. “That, for me, is probably the essence of democracy. Are we not allowed to criticize our critics too? Is it a one-way street?”

Observers and rights advocates, however, have pointed out that red-tagging is far from mere “criticism.” Individuals who are red-tagged are often subsequently charged with trumped-up allegations under the country’s hazy anti-terrorism law and are left to languish in prisons that are among the most crowded and inhumane in the world. And those are the somewhat lucky ones. There have been hundreds more red-tagged victims who have been summarily killed through the years, and many of them were hardly political dissenters and government critics. Aside from rights advocates, red-tagged victims have included environmentalists, lawyers, journalists, doctors, farmers, and indigenous peoples, among others.

In a country that is mainly Christian — with some 80 percent of the 117 million Filipinos identifying as Roman Catholic and another 10 percent as Protestant — church workers, priests, pastors, ministers and, yes, bishops, have also been red-tagged. Like many red-tagged victims, several of them have ended up dead.

Not a solely Philippine phenomenon

The practice is neither new nor confined to the Philippines. Across the world, other governments conducting whole-of-nation counter-insurgency operations do red-tagging. Newly canonized St. Oscar Romero of El Salvador is probably the most prominent victim of such operations that include religious targets.

Red-tagging, though, has become nearly synonymous with the Philippines in the last several years, and especially during the recently ended Duterte administration. And while the year-old administration of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has sought to have a gentler image than its predecessor, the picture on the ground has been less than reassuring.

Alminaza, for example, is among the more recent red-tagging victims. It all began for him last February via a television show, where his calls for peace and justice were also described as “diabolical and demonic” by hosts Lorraine Badoy-Partosa and Jeffrey Celis. Badoy-Partosa, a former Duterte presidential communications undersecretary, and Celis, alleged drug personality turned self-styled whistleblower against former comrades in the underground Left, have red-tagged many others, and are widely believed to be acting in behalf of the government’s counter-insurgency programs in their red-tagging spree.

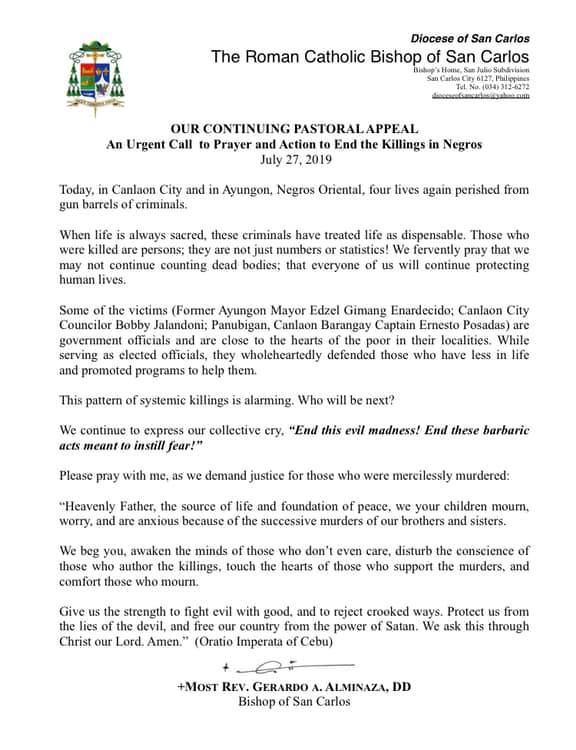

Alminaza seems to have wound up on the red-tagged victims list because of his strong human rights stance in Negros. In 2019, he ordered all the church bells in his diocese to ring every night at six o’clock to call for a stop to the rising number of killings on the island — reminiscent of the situation in Negros during the dictatorship of the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the incumbent president’s father.

Negros Island is the country’s sugar central. Its vast plantations are owned by very few landlords who pay their hundreds of thousands of farmhands starvation wages. The landlords are also the island’s politicians. Those who call for better living conditions and social justice in Negros are targeted for killing by the military, police, the landlords’ private armies, and paramilitary forces.

Today, under the Marcos Jr. administration, Negrenses, as the people of Negros Island are called, say that farmers, journalists, lawyers, rights defenders, land rights activists, and even politicians are being killed with horrendous regularity, several in massacre-style, among them a provincial governor and nine of his constituents earlier this year.

At the peace forum, Alminaza described the situation in Negros this way: “I drew to mind the 14 Negros farmers who were executed in the (government’s anti-drug and anti-insurgency campaign) Oplan Sauron SEMPO’s (Synchronized Enhanced Management of Police Operations) one-time, big-time operations of 30 March 2019. Two of them, Edgardo and Ismael Avelino, were part of a mission station under the Basic Christian Communities of the Diocese of San Carlos in Negros Occidental. I imagined the fright and terror of families being awakened before or near the break of dawn and the unbelievably similar police reports of “nanlaban (fought back)” killings. They had no due process, no legal counsel, no court hearings.”

“Red-tagging and terrorist-branding,” said the bishop, “can kill, have killed.”

Another bishop’s story

It is street wisdom also known to Bishop Antonio Ablon, who belongs to the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI). Now a political refugee in Europe, Ablon conducts his religious celebrations in grand, old churches. But he says that he misses his humble cathedral in his home island of Mindanao.

In June 2018, Ablon joined a fact-finding mission in Dumingag, Zamboanga del Sur in the Philippine south after learning that a Philippine Army unit’s presence in the Indigenous Subanen community had resulted in harassments, intimidation, and the arrest of two residents. On the mission’s second day, the soldiers ordered the bishop and his team to leave as “they did not coordinate with the military.” A colonel later paid the bishop a “friendly visit,” warning him not to disrupt “(the military’s) special projects in the area.” Ablon was also told not to publicize the information the mission had gathered.

The community suffered more harassment soon after. The soldiers went house to house and organized a “mass surrender ceremony” of alleged sympathizers of the New People’s Army (NPA, the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines). Bishop Ablon then facilitated another fact-finding mission, this time with the Commission on Human Rights, an independent state body, and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Three months later, in September, IFI churches were defiled and painted with “IFI = NPA!” Throughout northern and western Mindanao, streamers and traffic barriers screamed allegations of the bishop’s connections with the underground NPA, along with other faith groups such as the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines (RMP), the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), and the National Council of Churches in the Philippines (NCCP), among others.

Heeding the advice of several religious communities (including the Lutheran Church of Northern Germany, the Christian Catholic Church, and the global Anglican Communion), Ablon left the country to seek asylum in Europe in May 2019. Soon after, police officers barged into his cathedral, saying they were there to arrest him. When the deacon demanded to see an arrest warrant, the officers said it was merely a joke.

Ablon has since been appointed the IFI’s bishop in Europe, probably a reaction to dimming hopes of his safe return to the Philippines. In July 2020, then President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law the anti-terrorism bill.

‘Church of the Poor’

Ablon’s predicament, however, is not that known among Filipinos, many of whom are also unaware that IFI’s first ever woman bishop, Rt. Rev. Emelyn Gasco-Dacuycuy, and three of her clergy, had been accused of being New People’s Army recruiters. The entire United Church of Christ in the Philippines has been accused as well of being communist, as has the organization of mainline Protestants in the country, the National Council of Churches of the Philippines.

Filipinos are more familiar with the state’s persecution of the religious belonging to the Roman Catholic Church. Under the rule of the late dictator Marcos, for instance, a group of so-called ‘Magnificent Seven Bishops’ had been accused of having links with the underground communists for speaking out against rights abuses.

Ordained priests after the Second Vatican Council, the prelates’ attempts at building a “Church of the Poor” made them easy targets of allegations of having communist links. It was exactly the same crusade that made Alminaza, decades later, join his brother bishops in what the Church says is a persecution that Jesus has also suffered. Even the nuns of the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, the mission arm of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), have not been spared, their bank accounts frozen on allegations of abetting terrorism.

The spate of red-tagging against the clergy compelled Caloocan Bishop and CBCP president Pablo Virgilio David to denounce it in his 2022 Good Friday sermon, saying Jesus Christ was himself a victim of red-tagging, and was accused of being a subversive who wanted to bring down the Roman Empire that was ruling Judea at the time.

“[Jesus] was alleged to have been an organizer of poor fishermen in Galilee,” said David. “He was said to frequent far-flung areas where the rebellious zealots also were. He was alleged to be frequently seen in the deserts and mountains. And take note, he was related to a known activist prophet named John the Baptist, who spoke about the inconvenient truths of their time.”

It therefore came as a shock to many when the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict, the government’s main red-tagging apparatus, claimed that the CBCP had joined it. But David quickly clarified that only the conference’s Episcopal Commission on Public Affairs overseen by one bishop had joined the task force. He added that the CBCP was only acting according to its mandate of engaging the government as private sector representative. The CBCP for its part said it would keep in mind the Church’s thrust on justice in its engagement with the task force.

Ablon, meanwhile, remains unbowed, using his pulpit and his office in Europe to bear witness to continuing rights violations in the Philippines. He has spoken before the United Nations in Geneva and in the Swiss capital of Bern during the city’s ‘Night of the Religions.’

The Protestant bishop has tried to content himself with seeing his wife and younger son only through video calls. He said that when Marcos Jr., a Duterte ally, became president, “I realized that I may not see my family and home anytime soon.” ◉

= = = = =

This special report was produced in collaboration with the Asia Democracy Chronicles.