Despite persecution, seasoned missioners serve rural poor in Philippines

By Sr. Edita C. Eslopor, OSB/RMP

I have belonged to the Congregation of the Missionary Benedictine Sisters of Tutzing for 40 years, and since I am assigned to the remotest of the rural areas — serving those on the margins of society (the lost, the least and the last living) — I also work with the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines.

I have found my niche interacting with the sisters and lay mission partners from different congregations in the Philippines, and with parishes whose visions and missions share our common commitment to helping people in poverty. It is here that I genuinely appreciated the charism of our congregation. I am indeed grateful for God’s grace to persevere in my call to be a missionary in the Philippines.

From my experience, I could compare the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, as an organization, to a nutshell.

A nutshell is a hard covering in which the edible kernel of a nut is enclosed; it is sturdy and impenetrable and cannot be broken easily. If you strike it incorrectly, it will bounce back and be unchanged. The term in a nutshell is also used in writing or speaking to say something briefly, using a few words.

I was reflecting on this when the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines commemorated its 54th anniversary last August 2022. It had struggled through the pandemic; relentless “red-tagging” as terrorist or communist under the Anti-Terrorism Law; ongoing vilifications; killings; and freezing the group’s funds through the government’s Anti-Money Laundering Council. These funds should have been spent to help the rural people in poverty, especially peasants, Indigenous peoples, fisherfolk, and their people’s organizations.

Founded on Aug. 15, 1969, the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines is the oldest mission partner of the Conference of the Major Superiors in the Philippines. In a nutshell — Rural Missionaries of the Philippines is resilient and can weather storm after storm, for it is well-designed to serve the poorest of the poor in the rural areas in the Philippines.

Seasoned religious women, men and lay partners who espouse the vision, mission and goals of Rural Missionaries of the Philippines are at the helm of the organization. They have accomplished much and made a name here and abroad for more than five decades now.

They are a paragon of service to the rural poor. Hence, the group is closely watched and vilified by the powers that be, and red-tagged by the military because the missionaries are so down-to-earth. They remind me of what Pope Francis said when he instructed priests: “Be shepherds with the smell of the sheep.”

And how relevant is what Bishop Dom Hélder Câmara said: “When I give food to the poor they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.”

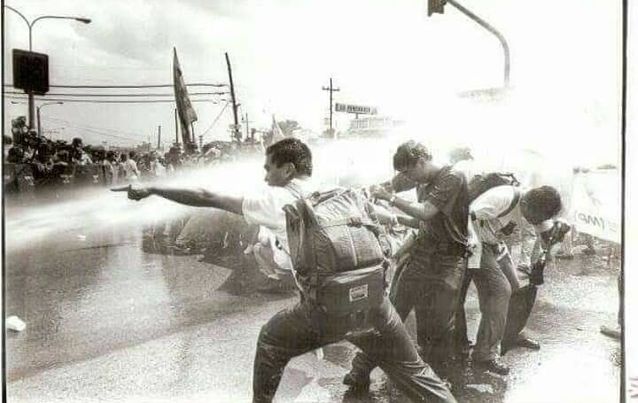

As the military unjustly attacked the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines by red-tagging them and freezing the funds intended for the peasants’ organizations, the missioners bounced back and continued to perform their missionary undertakings according to the saying: The mission is not ours; the mission is God’s.

The Rural Missionaries of the Philippines is home to different sisters, priests and lay mission partners from different congregations. They took to heart their mission and seriously looked at the signs of the times — not as an ordinary event but as a call and a challenge that needed a response.

What made these followers of Christ read the signs of the times with the eyes and ears of their hearts? The sisters who have led the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines through the years are visionary and extraordinary women at the forefront of contextualizing their faith. Their feat is amazing and worth emulating.

To celebrate how the group has enfleshed its God-given mission, I tried to itemize it:

- Five decades — of grateful and consistent journeying with the rural poor, partner organizations and funding agencies, to give birth to an organization of missionary doctors and health professionals (the Council for Health and Development);

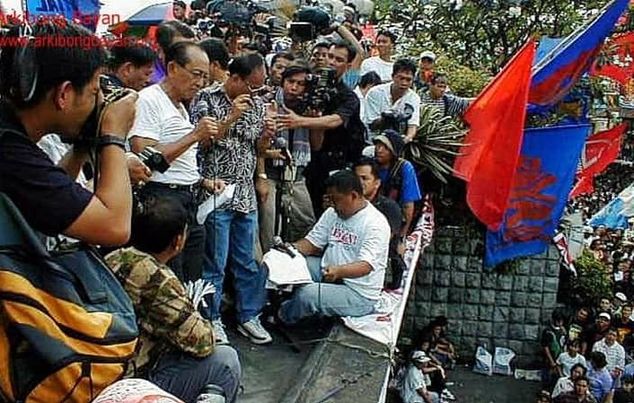

- 600 months — of meeting, assessing, planning to research, and attending rallies in solidarity with the people and other cause-oriented groups;

- 2,607 weeks — of breathing in the “smell of their sheep,” working with farmers, fisherfolk and Indigenous people, stressing the need to ally with the people’s organizations;

- 18,263 days — of talking the talk, facilitating fact-finding missions, medical missions, scholarship, and the like; of walking the walk with back-breaking responsibilities to help the people help themselves through their projects, thus empowering them;

- 18,438,312 hours — of home visiting, contact building, providing/facilitating task reflections/assemblies/exposure, sharing and praying the Bible in the context of the lived experiences of the poor people they serve;

- 26,298,720 minutes — of parrying the impact of the red-tagging and vilifying attacks from the military, of defending their God-given mission and congregational mandates, and of praying most earnestly for God’s guidance and protection.

As I lived my missionary life and when I looked to the lifelong members with their lean figures and malformed bodies, and dearly beloved departed missionaries, they always energized me beyond words. They mirrored the long years of great service and unwavering belief in the God of the poor and the giftedness of the people they served; their sacrifices for a cause they believed in; and their efforts without counting the cost that made their lives relevant and meaningful.

Francis reminded those who serve, “We must not forget that true power, at whatever level, is service.” Their whole worthwhile life is their humble offering back to God for the grace and care that God has bestowed on them through the years.

These people are awash with good memories of their experiences with the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines. Such a treasure — more precious than gold — is cherished in their hearts through the years.

Quo vadis, Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, in the next 50 years? This is a question often asked, given the worsening situation in the country and a lackluster Philippine president. But the missioners have the hope and a cast-iron certainty that God is always on the side of the poor, as he loved them and made so many of them!

As for those who served the people living in poverty, God will always bless them with peace and grace. The missionaries endured and will continue to persevere, for in the words of an African proverb, they stand tall on the shoulders of many ancestors.

The rural missionaries will move on with grit and determination. God’s grace transformed them into extraordinary missioners. And they take heart from St. Oscar Romero’s testimonial: “Even when they call us mad, when they call us subversives and communists and all the epithets they put on us, we know we only preach the subversive witness of the Beatitudes, which have turned everything upside down.” #

= = = = =

Editor’s note: Sr. Edita Eslopor was red-tagged herself and her community has missioned her to another location.

This article was originally published by the globalsistersreport.org.