Philippine mines continue unhampered 4 years after Gina’s shutdown order

In Benguet, critics are dismayed and wary of environmental degradation and natural disasters. The Chamber of Mines of the Philippines is also waiting for Malacañang to resolve the suspensions and “move mining forward.”

BY MARIA ELENA CATAJAN/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

What you need to know about this story:

- The late DENR Secretary Gina Lopez’s closure and suspension orders against 28 mines in 2017 were not implemented following a review ordered by Malacañang.

- A culture of non-implementation of environmental regulations has allowed mining companies to evade sanctions, according to former DENR undersecretary Antonio La Viña, a responsible mining advocate.

- Residents of two towns in Benguet are worried over the likelihood of disasters in mine sites and environmental destruction.

BAGUIO CITY — In July 2016, in one of her first acts as environment secretary, Regina “Gina” Lopez ordered an industry-wide audit of 41 large-scale mines in the country. Seven months later, 23 metallic mines received closure orders and five others were told their operations would be suspended.

A statement issued by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) dated Feb. 2, 2017 cited “serious environmental violations.”

“My issue here is social justice. If there are businesses and foreigners that go and utilize the resources of that area for their benefit and the people of the island suffer, that’s social injustice,” Lopez said in a press conference that day.

It was a quick move rarely seen against an industry that has significant contributions to the national economy. Mining stocks plunged.

Mining companies are big employers in rural areas –– over 180,000 workers nationwide, not counting indirect jobs created –– and contributed 0.5 percent to the economy in 2019.

In Benguet, a mineral-rich province in the Cordillera region, mayors of two mining towns covered by the order welcomed Lopez’s bold move albeit concerns for thousands of residents who stood to lose their jobs.

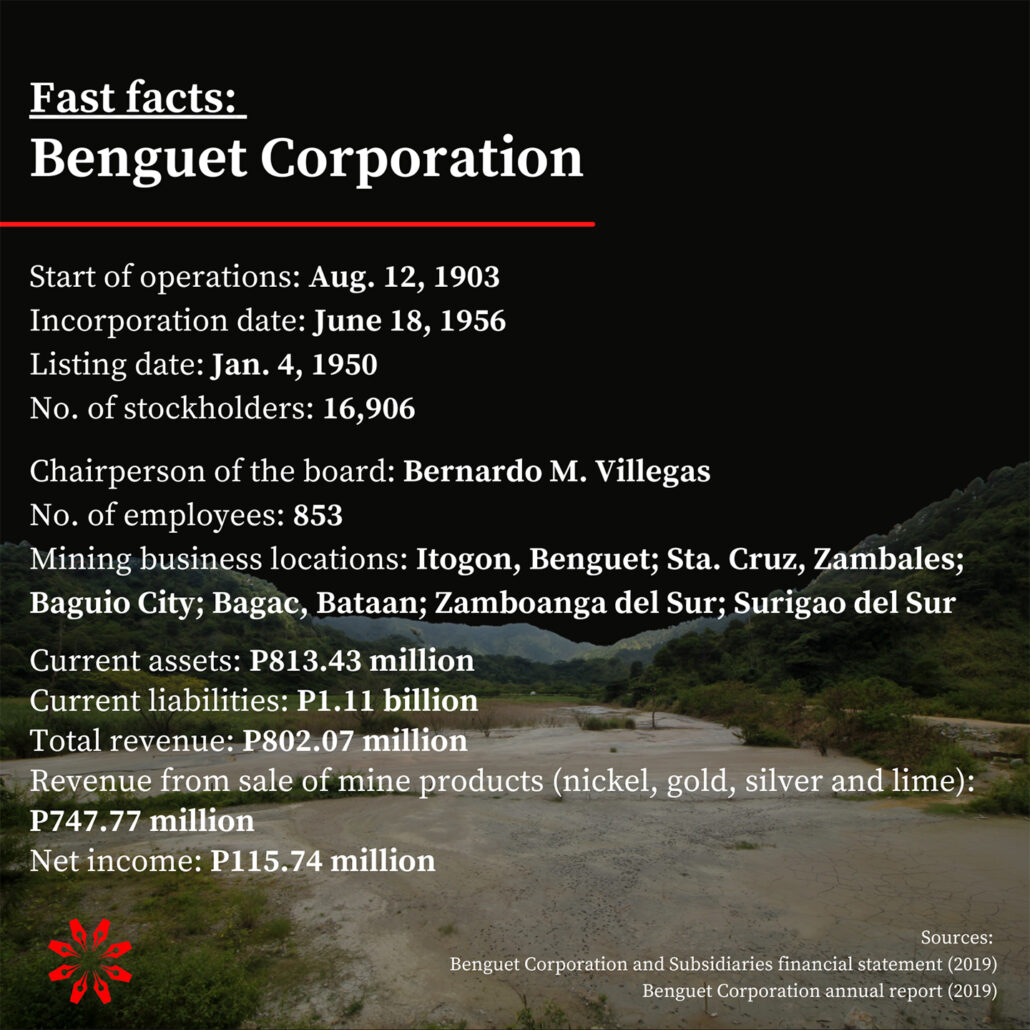

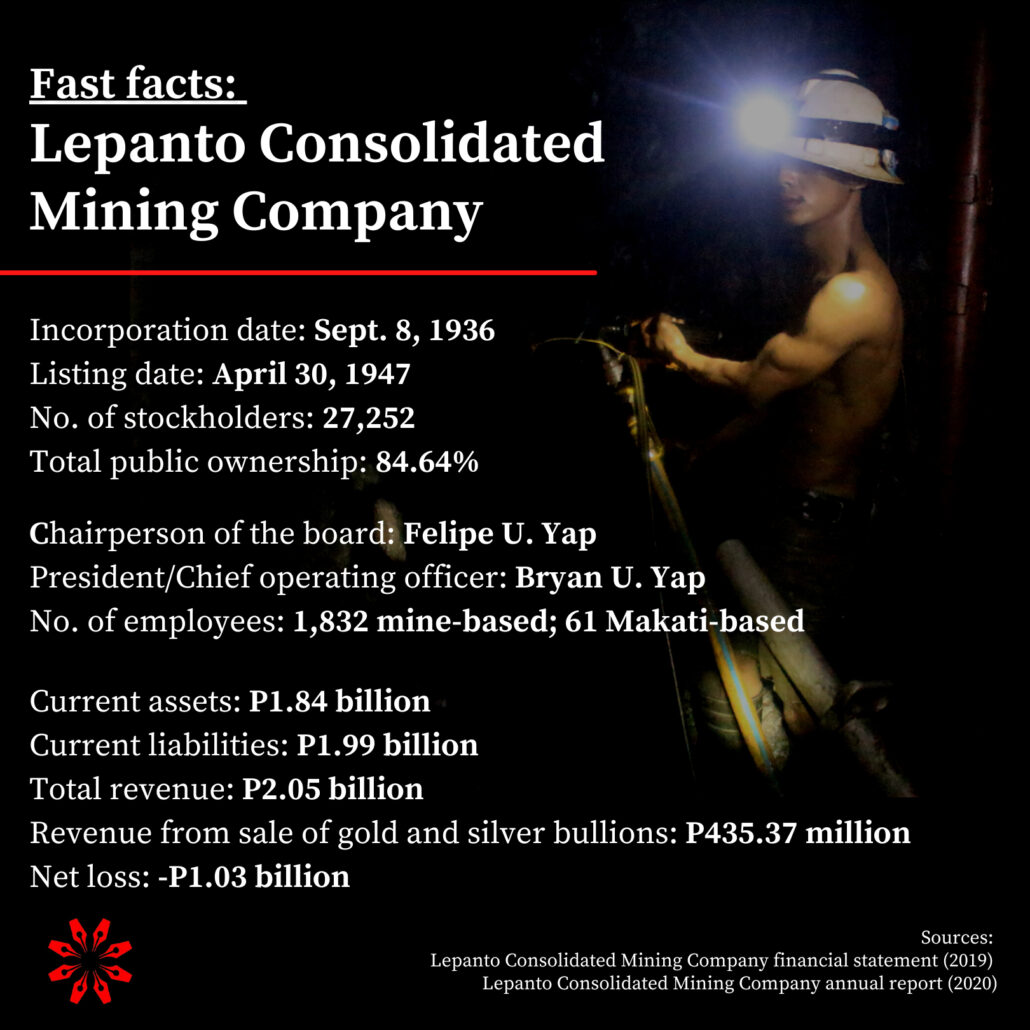

Operations of Benguet Corp. (BC) in Itogon and Lepanto Consolidated Mining Company (LCMC) in Mankayan were ordered closed and suspended, respectively. They are among the country’s oldest mines.

Itogon Mayor Victorio Palangdan has had a strenuous relationship with Benguet Corp., at times finding the company responsible for his town’s environmental problems. He is also backing demands of indigenous people’s organizations, which claim ancestral rights to the land, for a bigger share of BC’s profits.

Mankayan Mayor Frenzel Ayong also supported a closer look into Lepanto’s operations. “It’s a welcome development for the government to look into the details of the operation [of LCMC] as well as its compliances with the law,” he said.

Four years after Lopez’s crackdown,Benguet’s mines continue to operate to the dismay of civil society groups. Benguet Corp. and Lepanto did not cease operations except during strict lockdowns last year due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The mines that were served with closure orders by former DENR Secretary Gina Lopez were not closed at all and are operating after some of them appealed their cases to the Office of the President and the others to the DENR itself,” said Rocky Dimaculangan, Chamber of Mines of the Philippines (CMP) vice president for communications and national coordinator towards sustainable mining.

“If there are companies among the firms in the first round of MICC audit that were compelled to suspend their operations, it could be because of other violations outside the audit,” he said.

The mining companies immediately appealed their cases to President Rodrigo Duterte in 2017. The shutdown orders were put on hold amid warnings from the CMP then that shutting down mining companies would put 67,000 jobs at risk and cost the government up to P16.7 billion in taxes.

In Cordillera alone, mining companies employ close to 17,000 workers, with over 7,000 in large-scale mines and 10,000 in small-scale mines.

Duterte ordered the Mining Industry Coordinating Council (MICC) to review DENR’s audit. Lopez, who co-chaired the interagency body with Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, questioned the review.

Three months later, in May 2017, Lopez was kicked out as environment secretary after the Commission on Appointments rejected her nomination. She died two years later after a battle with brain cancer.

In an e-mailed response to PCIJ’s questions, Malacañang said it could not disclose its basis for allowing the mining firms to operate despite Lopez’s orders as it was “protected by the deliberative process privilege.”

“Albeit the proceedings herein are quasi-judicial in character, publicly divulging information and records, which include information on the nature of the case, violations allegedly committed, arguments of the parties, and other filings and pleadings made thereon by mining contractor-parties, relative to pending cases before this office is a violation of the sub judice rule as it constitutes blatant disregard of the same evils sought to be prevented by said rule,” said Ryan Alvin Acosta, deputy executive secretary for legal affairs.

‘Culture of non-implementation’

There has been no word about the MICC review or a final decision from Duterte on the mining companies that appealed to his office, although the DENR under Secretary Roy Cimatu in the last four years has upheld the closure of several mining companies and allowed others to operate again.

In Benguet, the Cordillera People’s Alliance (CPA) slammed the failure to implement Lopez’s orders against Benguet Corp. and Lepanto.

“The audit was the result of the long-standing struggle of the affected communities against the destructive operations of the mines. However, the suspension was never implemented. No mines in the Cordillera ceased their operation,” said Santos Mero, vice chairperson of the coalition fighting for the rights of indigenous peoples in the region.

Fay Apil, director of the DENR’s Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) in Cordillera, said they were still waiting for the MICC to confirm or refute Lopez’s audit on the two mines.

This goes to the “culture of non-implementation” of laws and regulations that has plagued the mining industry, said former DENR undersecretary Antonio La Viña, an advocate of responsible mining.

“It should have been decided quickly. This is why there is so much conflict in the mining industry. It’s an inherently risky activity and there are clear rules, but when rules are violated they are not enforced,” he said.

The DENR should also make sure its cases are airtight, he said, as mining companies have the money to pay the best lawyers.

La Viña said one thing going against the mining industry was its problematic public image because of a history of mining disasters.

“In theory, responsible mining is possible. The mining companies must follow the law. It needs strict compliance because of the destructive nature of the activity,” he said.

In one of the country’s worst mining catastrophes, the 1996 Marcopper disaster in Marinduque province released 1.6 million cubic meters of toxic mine tailings into the Boac River when a drainage tunnel was fractured. It caused illnesses that residents suffer to this day.

In Itogon in September 2018, 19 months after Lopez issued a closure order on Benguet Corp., disaster struckasclose to 100 small-scale miners taking refuge in a company bunkhouse and a church during the onslaught of Typhoon “Ompong” (international name: “Mangkhut”) were buried in a landslide.

Palangdan blamed the tragedy on Benguet Corp.’s operations, but the company pointed to illegal small-scale mining that it said it didn’t control. The bodies of the miners were not recovered.

Philippines’s oldest operating mines

Benguet Corp. has been in Itogon for more than a century, the oldest operating mine in the country. It started open-pit and underground mining operations in the town in 1903, employing thousands to extract ores of gold, nickel and silver.

It ended its underground operations in 1992. But when pocket miners invaded the Acupan tunnel –– one of two underground mines that formed the company’s gold operations –– the company opened it to investors and established the Acupan Contract Mining Project (ACMP).

ACMP saw a large-scale operator and groupings of small-scale miners working together under a mine lease agreement while it prepared the mines for the final phases of rehabilitation and decommissioning.

Benguet Corp. lawyer Froilan Lawilao said it was the first of its kind. MGB hailed it as a model for partnership between a large-scale corporate mine operator and small-scale miners.

Sixteen mining associations and cooperatives, involving up to 1,000 small-scale miners, operate their own pocket mines under a 60-40 profit sharing agreement.

Lopez however thought the economic benefits to the community did not outweigh the environmental dangers. She ordered the Itogon mines closed after the DENR audit found Benguet Corp. liable for the October 2016 mine tailings spill that contaminated a 1.6-kilometer stretch of the river.

The audit report said the company committed the following violations:

- operating a prohibited controlled disposal facility;

- maintaining and storing toxic and hazardous materials without an accredited Treatment Storage and Disposal (TSD) facility;

- failing to install air pollution control devices and apply for a permit to operate upon installation, and

- failing to rehabilitate the Antamok open-pit mine after it ceased its operations.

Benguet Corp. received the show-cause order on Oct. 28 and filed its reply on Nov. 1. The company claimed it had proof the findings were altered from an original version that declared the company compliant with mining laws.

Lawilao said company officials were told by DENR inspectors that Benguet Corp. passed the audit. A memorandum dated Aug. 16, 2016 stated that the company had complied with all legal and technical standards and “contributed to the local economy, except for some minor lapses.”

Lawilao also noted inconsistencies in the audit report, where the auditors allegedly interchanged the sites of Benguet Corp. with Lepanto. “These inconsistencies are serious and [indicates] the mine audit report was haphazardly prepared,” he said.

More disturbing was the “generalized finding of deficiencies for BC and Lepanto,” he claimed.

Benguet Corp., he explained, did not rehabilitate the Antamok open-pit mine because its operations were merely suspended. There are plans to reopen it.

And because Benguet Corp. began operations before the Mining Act of 1995, it was not required to deposit an approved amount for rehabilitation once operations cease.

When small-scale miners’ rushed to the Antamok mine site, it eventually prompted Benguet Corp. to apply for final decommissioning, which will turn the area into a Minahang Bayan. This will allow small-scale miners to operate legally and under the government’s radar.

Lawilao said the infractions committed by the company were “mostly permitting issues or operational concerns” that could be fixed without stopping their operation. Executives were surprised when they saw the news in September 2016 that Benguet Corp. was among the companies recommended for closure, he said.

“In a nutshell, we alleged that we were issued a stoppage order without any basis. The audit findings are not bases to suspend the mining company’s operation because these are minor offenses. We were just advised to implement remedial measures, like to register the [tailings] dam,” he said.

The Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) opposed Benguet Corp.’s plans to continue its mining operations in Itogon, however, and stood firm that it was time to return the land to the municipality.

“Imbes na i-rehab, mas inisip pa nito kung paano mas pagkakitaan pa ang lupain lalo na ang bahaging nasa ilalim ng kanilang mining patent (Instead of starting rehabilitation, it found a way to continue to profit from the land especially in areas under its mining patent),” the CPA’s Mero said.

“Halimbawa, ang mga proposal nilang rehabilitation is to transform the Antamok Open Pit mine para sa bulk water reserve ng Baguio. Noong hindi umubra ay gawin daw na sanitary landfill. Mayroon din silang pagtatangka na mag-venture sa real estate at pag-convert ng bahagi ng kanilang mining patent into an economic zone,” Mero added

(For example, there was a proposal to rehabilitate the Antamok Open-Pit mine by transforming it into a bulk water reserve for Baguio. When it didn’t work, they said they could turn it into a sanitary landfill instead. They also attempted to venture into real estate by converting parts of their mining patent into an economic zone.)

Mero was worried that disasters could strike again if the tunnels were not rehabilitated. “Many of the abandoned tunnels were not properly backfilled. These pose hazards to the community especially during continuous rains, strong typhoons and earthquakes. There are also reports that in their contract mining areas, they are now mining the pillars, further weakening the ground,” he said.

The people are better off finding alternative livelihoods, said Mero.

“More than 100 years of mining yet our town and its people remain poor. The [landslide during typhoon ‘Ondoy’ in 2009] and subsequent closure of SSM (small-scale mining) operations and the pandemic have totally exposed how hard life is in Itogon. Even if we host the oldest mining company, we are also concerned about the unrehabilitated tunnels and open pit mines,’ Mero said.

Benguet Corp. had been under the control of the Romualdez family until the administration of Duterte, when Benjamin Philip and Daniel Andrew Romualdez, sons of alleged Marcos crony Benjamin “Kokoy” Romualdez, left the company after decades of fighting government sequestration.

The economist Bernardo Villegas, an independent director, was installed as chairman in late 2019. The company reported nearly P116 million in net income that year on revenues of P802 million.

Lepanto: First copper concentrator

Lepanto, on the other hand, was established in 1936 and was the first to operate a copper concentrator in the Philippines.

The company alone employs over 2,000 employees and boasts of its ISO certificate, first issued on May 12, 2016, stating that the company had complied with environmental management standards.

The audit report said Lepanto committed the following violations:

- dumping mine tailings directly to the river;

- violating health and safety regulations;

- maintaining and storing unregistered TSD; and

- operating a controlled dumpsite.

Lepanto also contested the 2017 suspension order that cost the company over P1.8 billion, the company’s resident manager Thomas Consolacion told reporters then.

It was granted a stay order on Oct. 12, 2017 after it filed an appeal with Malacañang. The company was ordered to pay P27,275 in fines to the MGB and P100,000 to the Environmental Management Bureau. Lepanto also agreed to monthly inspections.

Read Lepanto’s memo on the lifting of the suspension order here.

PCIJ reached out to Lepanto corporate communications head Butch Mendizabal for an interview and for copies of the suspension order and appeal it had filed with Malacañang. The company declined both requests.

Notwithstanding Lepanto’s ISO certification and support from residents directly employed by the company, protests from host and downstream communities hound the industry giant.

The call to cancel Lepanto’s mining permit started in 2002 when local scientists, health professionals, and academicians formed Save the Abra River Movement (STARM) with a series of environmental investigative missions and studies from 2002 to 2005, which yielded proof of the river’s decline due to mining.

Communities dotting the Abra River banks have long attributed the rivers’ siltation and pollution to Lepanto’s operations, endangering the people’s primary source of irrigation, fishery and other livelihood.

“Abra River is an integral component of the broad people’s call for Lepanto’s closure,” said Mero.

From Benguet, the river flows to the municipalities of Cervantes, Quirino and San Emilio in Ilocos Sur, and traverses the towns of Luba, Manabo, Bucay and Bangued in Abra. Its waters meet the West Philippine Sea in Santa, Bantay and Caoayan, also in Ilocos Sur.

“When the company started, there were still no laws prohibiting the dumping of waste directly into the bodies of water. For decades, Lepanto disposed of its waste in the streams, which eventually found their way to the main river system,” said Mero.

Companies were allowed to use natural water bodies for their mine wastes provided that these were treated. The company used to course mine waste through a tributary creek connecting to the storage facility.

Lepanto built its first dam to contain silt and wastewater in the 1960s, but the company suffered three dam failures until 1993, releasing volumes of tailings to the river and destroying rice fields along its banks.

In the municipality of Santa in Ilocos Sur, Lepanto’s tailings dam poses a threat to all communities along the Abra River. “We are the catch basin. All waste from upstream will eventually reach our communities here, where the river exits,” said Vice Mayor Jeremy Bueno.

In March 2017, during the hearing of the House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources in Baguio City, Bueno told lawmakers that “Lepanto’s Tailings Dam 5A on the Abra River’s headwaters is a clear and present danger to life in the entire river basin.”

Bueno said his position on the matter remained the same. “There has been no significant change, even when the company was ordered to cease its operation, the looming threat from the tailings dam remained,” he said.

In 2004, Lepanto faced fines for polluting the Abra River. It was penalized by the Pollution Adjudication Board after failing the effluent standards required on rivers. The government slapped the company with minimal fees in the same year.

The Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) launched another probe in 2008. A test conducted in April that year found that lead content in Dam 5A exceeded the normal lead levels. The research findings and succeeding pollution probes by the EMB further strengthened the call for Lepanto’s closure.

But MGB’s Apil said Lepanto made adjustments to its operations before Lopez’s audit report came out, piping its tailings from its mills to a tailings dam in compliance with her orders for all mines to stop channeling their waste through bodies of water.

Lepanto recorded heavy losses in 2019. Its net loss widened to P1.03 billion from P775 million as revenues dipped 3% to P2.12 billion amid weak gold trade in 2019. The company was controlled by the family of businessman Felipe Yap.

Sinking towns

The environmental issues in Benguet’s mining towns are beyond the findings of Lopez’s audit report.

In October 2015, a sinkhole measuring about 150 meters swallowed six houses during the onslaught of Typhoon “Lando” at Sitio Kamangaan in Barangay Virac in Itogon.

Later, about 500 more houses were identified to be at risk of being swallowed by the sinkhole.

A report by the National Institute of Geological Sciences of the University of the Philippines (UP) said the subsidence was caused by a pipe out that started at the old drain tunnel of Benguet Corp. Heavy rains triggered the collapse of soil.

At that time, Mayor Palangdan insisted Benguet Corp. must admit responsibility for the Virac sinkhole and stay true to a promise to rehabilitate the mine. The sinkhole created a five-hectare danger zone.

But Benguet Corp. did not take responsibility for the sinkhole. Instead, it offered remedial measures and a relocation site at their old timber yard, former dumping grounds of the mining firm. However, resettlement is being hampered by disputes between land claimants and the mining company.

Those rendered homeless have since been renting homes while BC employees were given temporary resettlement.

In 2018, when Typhoon “Ompong” struck, Palangdan was ready to renounce mining and go back to farming after small-scale miners were buried alive in a landslide widely attributed to the town’s mining operations.

He lamented how the town was destroyed, forcing people to look for other means of livelihood.

Benguet Corp. again denied responsibility for the landslide and said illegal mining and gold processing activities were carried out without its permission.

MGB also attested that the landslide was not caused by mining alone, as there were aggravating circumstances.

Environment Secretary Cimatu immediately ordered a halt to small-scale mining in the Cordillera and deployed soldiers and police to enforce the ban, sealing all tunnels.

The death of the miners revived calls for the opening of a common mining site under the “Minahang Bayan” scheme for small-scale miners.

The Minahang Bayan centralizes the processing of mineral output within a zone, helping curb illegal, unregulated and indiscriminate mining. It also allows the government to better monitor gold production by small-scale miners.

In 2019, a Minahang Bayan permit was awarded to the Loakan Itogon Pocket Miners Association (LIPMA) within the patented mineral claims of Benguet Corp., which endorsed the application.

In Mankayan, sinking was first observed in 1972 or almost four decades after Lepanto started mining operations.

The subsidence has crept into the villages of Colalo and Poblacion, pushing former Mankayan mayor Materno Luspian to call for an independent probe to find the cause and solution to the perennial danger.

In 1975, a team from the then Bureau of Mines, Commission on Volcanology and Bureau of Public Works investigated ground movement in Barangay Poblacion.

The team found cracks along concrete pavements, house floors and walls, and displaced posts. Buildings and structures were found to be below standard and erected over weak foundations.

The probe found no conclusive evidence that underground work at the mines caused ground movement. Sinking was attributed to rainfall, topography, highly fractured and altered overlying rocks as well as disturbance of the slope by man and nature.

‘Bold moves need support’

Lopez’s Feb. 2, 2017 order was contentious even inside the DENR. Protocol was not followed, too.

Apil said the DENR didn’t normally slap mining companies with outright suspension orders. Usually, the DENR informs the company first about its violations and gives it time to comply.

The audit report was also submitted directly to the DENR central office in Quezon City, bypassing the regional offices. “Unfortunately, we were not provided [with the report] here in the region. It was only there, at the DENR central office that they vetted the results,” Apil said.

Mero said it resulted in confusion on the ground. It was not clear what agency was to enforce the directive and ensure the shutdown of mines. The MGB regional office had minimal participation in the audit, he said.

On Aug. 9, 2019, MGB’s Cordillera office recommended the permanent lifting of the suspension order against Lepanto after it said the company fully complied with all the requirements set by the MICC.

On Jan. 9, 2020, Apil also endorsed granting Benguet Corp.’s appeal against the closure order but imposed conditions that the company would implement its corporate social responsibility programs.

Four years after Lopez’s shutdown orders, the status of Malacañang’s review is still unknown. CMP’s Dimaculangan said the MICC scheduled a second round of audits in early 2020 although he said he’s unaware if this was completed.

Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque told PCIJ he’d defer to Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, whose office refused to divulge information on the specific cases.

The CMP said it was also waiting for Malacañang to finally resolve Lopez’s shutdown orders and “move mining forward,” citing the industry’s potential to contribute to economic recovery amid the coronavirus pandemic.

“To achieve this, we believe that the government should resolve the suspension orders issued by former Secretary Lopez, which is still pending with the Office of the President, after compliance with any corrective measures recommended by the MICC,” said Dimaculangan.

President Duterte, who has kept the previous administration’s ban on open-pit mining, has repeatedly warned he would shut down mining operations in the country if miners didn’t follow tighter environmental rules.

But it was clear that Duterte didn’t have as much zeal for Lopez’s crusade, said La Viña, as when he ordered the shutdown and rehabilitation of the tourist island of Boracay in 2018.

“The lesson there was: You have to do bold things with the support of the president,” said La Viña. –– With research and reporting by Sherwin de Vera and Lauren Alimondo, PCIJ, January 2021

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.— PCIJ