From Brazil to Kosovo to the Philippines, confined citizens protest from their windows

A COVID-safe way to capture the attention of politicians

By Jose Carpintero Molina, Fernanda Canofre and Raymond Palatino

There is a very good chance that you’re in lockdown as you read this. One in every three people on earth is under some sort of social distancing order as governments scramble to slow the spread of COVID-19, which has claimed more than 100,000 lives since the novel coronavirus was first detected in China in December 2019.

Lockdowns have been watched vigilantly by rights groups, who are urging governments to tread carefully when restricting civil liberties in these exceptional circumstances. But lockdowns do present a paradox for accountability on that very matter: How can citizens ensure officials don’t misuse their new emergency powers when public protests present an immediate danger to one other?

Fortunately, people have found alternatives. From Kosovo to Spain, from Brazil to the Philippines, pot-banging from balconies and windows emerges as a COVID-safe way to capture the attention of politicians.

Of course, such demonstrations are nothing new. As documented by historian Emmanuel Fureix, this type of protest was first seen in France in 1830. Back then, when the Republicans opposing the Louise-Philippe monarchy used kitchenware to make noise as a sign of protest, it was called charivari.

This method of resistance later reached other parts of the world. In 1961, during the Algerian war of independence one protest became known as “the night of the pots.” Other popular protests of this kind took place in Chile in 1971, during the Allende administration, in Quebec during the 2012 student protests, and in Turkey, during the 2013 Gezi Park protests. Today it is particularly popular in Latin America, where it’s known as cacelorazo, and panelaço in Brazil.

From their windows in Kosovo, citizens begged authorities to put lives before politics

In Kosovo, citizens banged pots and pans from the balconies and windows every night for a week to show discontent with the current political situation — a power struggle in the ruling coalition over the emergency measures.

The protests did not prevent the prime minister from losing a no-confidence motion on March 25, making Kosovo’s government the first in the world to fall in relation to the coronavirus crisis.

With the Kosovo government ousted, the decision to either form a new government or dissolve the country’s parliament and call for early elections falls to President Hashim Thaçi, the main beneficiary of the prime minister’s sacking. However, holding elections in the midst of a pandemic seems impossible, leaving various important issues up in the air:

In Spain, a cazerolada against the king

On March 19, 2020, as the King of Spain, Felipe I, gave a nationally broadcasted speech asking for unity in confronting COVID-19, people went to their windows and balconies to demand that his father, Juan Carlos I, donate to the public health system the 100 million euros he allegedly has in a Swiss bank account, courtesy the King of Saudi Arabia.

Just a few days later, a similar protest was held against Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez and his government, as a criticism of their handling of the COVID-19 pandemic:

“Banging pots and pans for a while. Pedro Sanchez RESIGNATION, in Capitán Haya, Madrid.”

On April 1, right-wing and far-right again called on social media under the hashtag #cacerolada21h for a protest from the balconies against the government’s handling of the COVID crisis. However, this call ended up having little or no success in some parts of Spain.

One month of nightly protests against Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro

Since March 17, pots and pans have been echoing from Brazilian households at around 8:30 p.m. every night, in protest over how President Jair Bolsonaro is handling policies to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic in a country with 200 million people:

The first night of protests actually took place a day before the original date that had been planned via social media channels. In cities spanning from the north to the south of the expansive country — even in neighborhoods that used to bang those same kitchen utensils asking for the impeachment of left-leaning president Dilma Rousseff four years prior — people shouted, “Get out, Bolsonaro!”

The following evening, March 18, only half an hour after the protests began, Bolsonaro tried to turn this act of resistance on its head by calling for people to bang pots and pans in support of his government:

“The Today News (TV Globo) and Veja [magazine] ostensively publicize POTS AND PANS PROTEST tonight at 20h30 against President Jair Bolsonaro.

– But the same press, who claim to be impartial, DOT NOT PUBLICIZE another POTS AND PANS PROTEST, at 21h IN SUPPORT OF JAIR BOLSONARO’S GOVERNMENT.”

The Brazilian president has been downplaying the effects of the pandemic, calling COVID-19 “a little flu” and labeling media coverage and social isolation measures adopted by state governors as “hysteric”. In several states, roads have been blocked, interstate buses have been suspended, events canceled and schools closed.

Bolsonaro has given three televised addresses to the nation since World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11. His messages have been described as confusing and erratic, at times directly criticizing state governors and at others calling for “union.”

Over the past two weeks, the Brazilian president has shifted from calling for schools and commerce to be reopened, to defending “vertical isolation” — the kind imposed only to people in high-risk groups — and, like US President Donald Trump, advocating for ample use of chloroquine against COVID-19, despite the lack of enough scientific evidence of its efficacy.

Surrounded by aides and cameras, Bolsonaro has also gone several times on walkabouts around the capital Brasília, speaking to and shaking hands with supporters. On his latest excursion on April 10, he declared: “No one will curb my right to come and go.”

Allies and leaders of the National Congress have criticized him for going against the recommendations of the WHO.

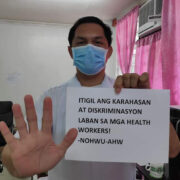

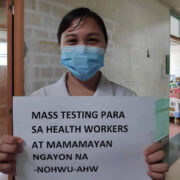

#ProtestFromHome in the Philippines

Kadamay, an urban poor group in the Philippines, organized noise barrage protest actions to highlight the slow delivery of food assistance from the government. The lockdown order it was under, though aimed at containing the COVID-19 outbreak, also disrupted the livelihood of street vendors and other workers from the informal sector:

The lack of a clear plan on how to extend assistance to poor households prompted Kadamay to organize the protest, which involved the banging of empty kaldero (pots) in houses. The Twitter hashtag #ProtestFromHome trended on March 22, after the campaign gained online support in the country. The police responded by accusing Kadamay of being anti-Filipino.

The protest also asked that the government conduct mass testing for COVID-19 and prioritize the sending of relief to affected communities.

Argentine women pot-bang against domestic violence

In Argentina, the sound of kitchenware was also heard in protests over the increase in violence against women during quarantine. Thousands of women were involved in these protests, which also called for the lowering of politicians’ wages:

“This Monday night, a cacerolazo was heard in different neighborhoods of Buenos Aires. Under the hashtag #Ruidazo, calls were made to reduce wages in the political sector amid the coronavirus pandemic.”

Protect the vulnerable in Uruguay

Beating pots and pans was also the method that many Uruguayans used to call for social protection measures for the most vulnerable during the COVID-19 crisis, though others did attempt to counteract it by playing the national anthem and applauding:

“With hymn and tutti #SuenaUruguay #uruguay #montevideo #cacerolazo“

Just as global citizens are bound together in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems that at present, when street protests are impossible, they are also united by banging pots and pans. #

= = = =

Kodao reposts Global Voices articles as part of a content-sharing agreement.