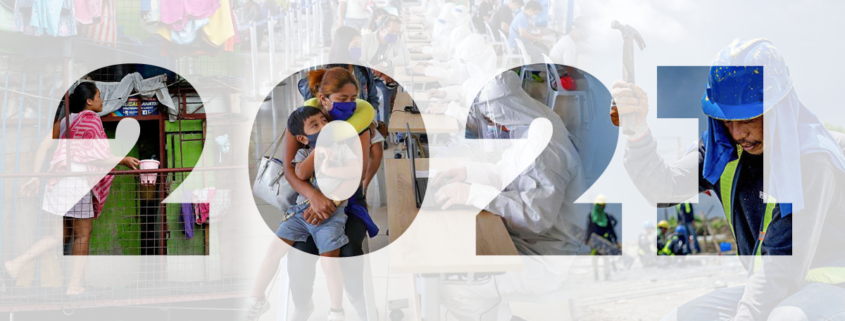

Yearender: Unrepentant economics in 2021

IBON Foundation

The Duterte administration is weirdly fond of congratulating itself for having “game-changing” economic reforms. It first used the term to refer to tax packages crafted in 2016, then subsequently kept using it to describe all of its pet measures – infrastructure spending, rice liberalization, health financing, tax reform, national ID system, ease of doing business, and so on. It still smugly back-pats itself as 2021 draws to a close.

The choice of a sports metaphor favored by the business community is actually revealing. For the economic managers, managing the economy is really about making big business prosper most of all. It’s unfortunately not about doing everything to improve people’s lives or alleviate their distress. It’s not even really about the businesses of the little folks – micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Throughout 2021 and to its very end, such as in slow and stingy typhoon Odette response, the Duterte administration is leaving ordinary people behind.

Rebounding

There was so much to do after 2020. The unnecessarily long and harsh lockdowns caused the worst economic collapse and joblessness since national accounts and labor force trends started to be recorded after the end of the Second World War.

Public health measures to contain the pandemic still should’ve been foremost – free mass testing, methodical contact tracing, and judicious quarantines. But the government grossly underinvested in all of these while reopening the economy.

Especially because vaccination was among the slowest in the region, this resulted in daily COVID-19 cases and deaths generally increasing through most of the year until September. At its worst, there were eight times as many cases and four times as many deaths in 2021 compared to the peaks in 2020.

The Duterte administration also refused to stimulate the economy beyond empty statements and inflated “game-changing” rhetoric. The end result is an economy that merely rebounded and is still a long way from recovery. As ever, it’s the poor who are worst off.

More rapid economic growth gave the illusion of recovery. This was however just inflated in coming from the record collapse and low base in 2020. The reported 4.9% gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the first three quarters of 2021 is from a huge -10.1% growth (contraction) in the same period last year. It still doesn’t make up even half of what the lockdowns cost the economy.

As it is, quarterly economic output is still just as low as it was three years ago in 2018. Most sectors have lost two to as much as 11 years of output. Transport, hotels and restaurants are among the most badly hit and only a few tycoon-dominated sectors like utilities and finance kept growing. GDP per capita is meanwhile down to 2017 levels.

Rough going

The crisis doesn’t affect everyone the same. On one hand, poverty by official standards grew 3.9 million to 26.1 million Filipinos in the first semester of 2021. This estimate of one out of four Filipinos poor (23.7%) is according to a low poverty threshold of just some Php79 per person per day though – as if Php80 a day is enough to escape poverty.

The number of poor and vulnerable Filipinos is more likely closer to 18 million families or some 78 million Filipinos. Around seven out of 10 households (69.8%) didn’t have any savings as of the fourth quarter of 2021. Self-rated poverty surveys meanwhile have some 79% of families reporting themselves as poor (45%) or borderline poor (34%).

These are huge numbers of families with little capacity to deal with economic shocks or calamities. It’s interesting how they might react to administration propaganda of “a strong and early recovery”.

Such poverty also belies claims that the labor market is improving. According to labor force surveys, employment is up 1.3 million in October 2021 from January 2020 before the pandemic. The devil however is in the details.

The most obvious understated detail is that officially reported unemployment over that same period is also up by 1.1 million to 3.5 million. Even by just this, the Philippines already has the worst unemployment in the region.

But the true rate of unemployment (TRUE) is probably even higher at around 8.2 million or more – consisting of official unemployment (3.5 million), correcting for the 2005 change in definition which cut those counted as jobless (initially estimated at 1.5 million), and unpaid family workers (3.2 million).

Yet the reported 1.3 million increase in employment is also misleading and doesn’t really indicate decent-paying work. This net employment creation since last year is wholly informal in irregular self-employment and unpaid family work. The increase reflects millions of Filipinos just trying to get by however they can, especially those who lost their jobs because of the lockdowns.

In terms of hours worked, the number of full-time workers is down by 1.4 million (to 27.3 million) while part-time workers bloated by 2.6 million (to 16 million).

By class of worker, there are 369,000 less wage and salary workers (down to 27.4 million); this includes 621,000 less work in private establishments only partly off-set by increased public sector jobs.

Laid-off workers and others seeking livelihoods made do with merely informal work which bloated by 1.7 million. The number of self-employed increased by 758,000 (to 11.9 million), employer in own farm or business by 354,000 (to 1.4 million), and unpaid family workers by 541,000 (to 3.2 million).

Amid govt back-patting on merely rebounding economic growth, much more ayuda to poor households and assistance to distressed MSMEs is critical to even just start to recover. This fixes the lockdown-induced collapse in aggregate demand especially among families – made worse by rising inflation since last year – and the corresponding closures and reduced operations of MSMEs.

Extrapolating from a trade and industry department survey, around 96,000 MSMEs closed shop while some 460,000 were only partially operating as of June 2021. This probably still doesn’t include tens of thousands more troubled but unregistered small businesses.

Riches

The majority of Filipino grappled with joblessness, falling incomes, depleted savings, and high prices. On the other hand, the country’s wealthiest continued to prosper often with timely government support.

The combined wealth of the 50 richest Filipinos recovered quickly and grew 30% in 2021 to US$79.1 billion (Php4 trillion). Among the biggest gainers were close Duterte allies – Manny Villar’s wealth grew 32% (to Php327 billion), Ricky Razon’s by 33% (Php283 billion), Ramon Ang’s by 13% (Php112 billion), and Dennis Uy’s by 7.5% (Php35 billion).

The Duterte administration supported big business through the pandemic. Publicly-funded road, bridge and rail projects under its Build, Build, Build infrastructure program boosted the property values of tycoons’ real estate projects and increased traffic to their port terminals. The Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises (CREATE) law cut the corporate income taxes they pay, increasing large enterprises’ profits by some Php70 billion – and reducing government revenues by the same amount – just in 2021.

Pres. Duterte and his economic managers actually acknowledge their inaction and justify this by claiming insufficient government resources. The president is folksy and says there’s no money. The economic managers have a fancier term – fiscal consolidation.

Restraint

By any name the Duterte administration’s restraint is self-defeating in so many ways. Insufficient spending on public health measures increases the risk of a COVID-19 surge if new variants are more transmissible or vaccine-resistant.

Insufficient spending on ayuda doesn’t just make families suffer disproportionately from the over-reliance on lockdowns. It also represses consumption spending and aggregate demand, especially amid worsening job scarcity.

Insufficient spending to help MSMEs stops them from reopening or expanding – tightening aggregate supply and, through less hiring and lower pay, aggregate demand as well. All of this put together makes recovery uncertain and unnecessarily protracted.

The insistence that there’s no money is actually suspect. The government had a budget of Php4.3 trillion in 2020 and Php4.5 trillion for 2021. This was supported by considerable borrowing – Php2.7 trillion in 2020 and Php2.8 trillion so far in 2021.

Little of the government budget (and debt) actually went to COVID-19 response. The budget department reports just Php570 billion in disbursements for COVID-19 under Bayanihan 1 and 2, the 2020 GAA and the 2021 GAA as of September 30, 2021. This is barely half the US$22.5 billion or around Php1.12 trillion that the finance department claims to have secured in financing for COVID-19 response as of September 5, 2021.

So what has the Duterte administration been spending on amidst the biggest public health and, arguably, humanitarian crisis in decades? So far in 2021, it has spent Php702.4 billion on infrastructure (as of October) and paid Php1.13 trillion in debt service (as of November). In either case, much more than on COVID-19 response.

This just points to the Duterte administration’s real priorities. It is just using COVID-19 response as smokescreen for hugely bloated borrowing to compensate for lost revenues because of its over-reliance on lockdowns, to keep financing its grandiose infrastructure program benefiting a few, and to keep creditors happy.

For argument’s sake, would the government spend more on relief and disaster response if it had the resources? Apparently not. The economic managers are actually expecting to have some Php260 billion more than expected in 2021 – with Php150 billion more revenues and Php110 billion less spending in 2021 than targeted.

Instead of using this to alleviate extended suffering since the lockdowns hit and which was compounded by typhoon Odette in the closing weeks of the year, it is keeping this untouched to prettify its deficit targets for the sake of creditworthiness.

Realities

Little improvement can be expected in the last few months of the administration’s term when it will be most of all concerned with navigating conflicting political ambitions in the May 2022 elections. The short-sighted drive for power will, once again, trump the long fight against poverty and underdevelopment.

The coming year is looking to be tumultuous for the economy. A surge is already likely in the opening weeks of the year and will stoke uncertainty. Minus the base effect from the 2020 collapse, the economy will return to its pre-pandemic trajectory of decline – further weighed down by high unemployment, informality, and other economic scarring. If ever, a return to power of the Marcoses in the 50th anniversary year of martial law will signify dysfunctional politics taking a turn for the worse.

The consequences for the country are unclear but will almost certainly be profound. #