In Metro Manila, Fighting COVID-19 Requires Helping the Poor—Now

Old methods of emergency response no longer apply.

BY ICA FERNANDEZ & ABBEY PANGILINAN WITH DR. MIGUEL DOROTAN, NASTASSJA QUIJANO, PATRICIA MARIANO, ZAXX ABRAHAM, CLARA BUENCONSEJO, BENEDICT NISPEROS, DAVID GARCIA, & MIRICK PAALA. MAPS BY JR DIZON/MAPADATOS. PHOTOS BY KIMBERLY DELA CRUZ. (URBANISMO/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism)

A SURGE of COVID-19 cases is expected to hit Metro Manila in the coming weeks and the city is grossly unprepared.

Home to nearly 13 million, Metro Manila is the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the country. Despite the government’s aggressive efforts to contain the pandemic by sealing off the capital and shutting down businesses and transport, the contagion is likely to spread and worsen.

The hard facts

Data scientists from the Asian Institute of Management estimated 26,000 COVID-19 cases in the Philippines by end-March. Many, if not most of these cases, will be in Metro Manila, which has accounted for more than half of the 636 recorded COVID-19 cases as of March 25. Most of the 38 recorded COVID-19 deaths were also in the capital.

As the table below shows, there are not enough doctors and nurses to cope with the projected surge in cases. Moreover, most health care workers are employed in the private healthcare system, which caters to only about a third of the population. Nearly 70 percent of some 1,500 hospitals in the country are privately owned.

There is already a shortage of doctors and nurses. In a recent Senate hearing, Philippine General Hospital Director Dr. Gerardo Legaspi said there should be at least 44 doctors, nurses, midwives, and medical technologists for every 10,000 Filipinos. The ratio is currently at 19 per 10,000.

Table 1. Distribution of Health Workers in Government Hospitals

| Doctors | Nurses | Midwives | Dentists | |

| Philippines | 10,447 | 30,368 | 16,610 | 1,812 |

| Metro Manila | 3,890 (37%) | 8,161 (27%) | 1,947 (12%) | 599 (33%) |

Source: Department of Health, 2018

To date, two major hospitals in Metro Manila, the Medical City and the University of Santo Tomas Hospital, have had to quarantine 674 exposed health workers. Four high-end private hospitals— St. Luke’s BGC and Quezon City, Makati Medical Center, and The Medical City in Pasig City—have now said that they are unable to attend any more COVID-19 cases.

Equally worrisome, a recent Philippine College of Physicians survey revealed only 1,572 ventilators are available in the country, 423 of them in Metro Manila. Global estimates show that 3 to 5% of COVID-19 patients require mechanical ventilation, crowding out others like stroke and heart attack patients who need intensive care.

Even as the Department of the Interior and Local Government ordered local governments to set up isolation facilities for milder COVID-19 cases that do not require admission to hospitals, not all barangays have been able to comply.

“Flattening the curve”—keeping the infection growth rate down—and protecting hospital frontliners means keeping people at home so the virus doesn’t spread. While at home, people must be fed and their health and sanitation needs must be provided for right in the places where they live.

The COVID-19 battleground, therefore, is not just hospitals, but the poorest communities that lack the means to feed and protect themselves. Protecting these communities means protecting everyone else.

The issues: Poverty and density

Metro Manila is one of the densest cities in the world, outstripping Delhi, Paris, or Tokyo. It produces 70% of the country’s economic output and is the center of political, cultural, and economic life in Luzon. But it also has one of the largest concentrations of poverty. Some 2.5 million of the city’s nearly 13 million residents live in slums, while 3.1 million are homeless.

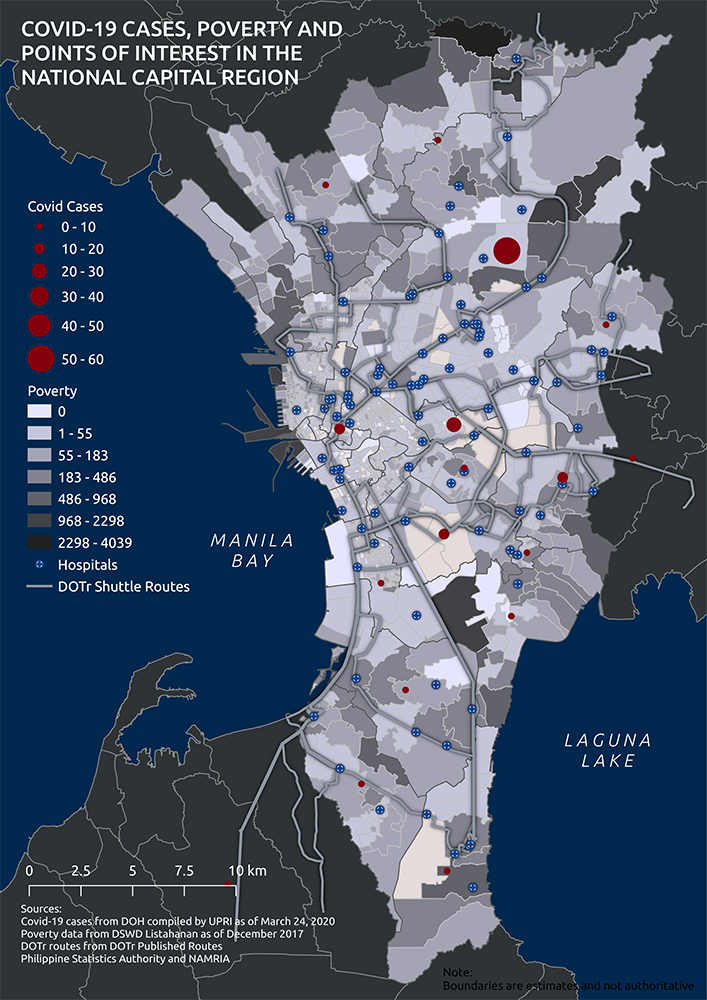

This map shows the poorest areas of the capital (the darker the color, the larger the percentage of poverty in the area) and their proximity to hospitals and COVID-19 cases.

Note: The poverty numbers in the map above refer to the number of poor households in each barangay that have been identified through the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction, the government’s primary database of who and where the city’s poorest and neediest are. The numbers indicate families that have been targeted by the Department of Social Welfare and Development for social protection programs such as conditional cash transfers. These families are the poorest of the poor but their numbers do not include the homeless and the so-called “near-poor,” who are equally vulnerable.

In these poor communities, families are packed in small shanties with 4 to 6 children plus several extended family members, including grandparents, sharing small spaces. Social distancing in these cramped places is difficult, if not impossible.

The Issues: Access to health, sanitation, mobility, and food security

Even without COVID-19, poor living conditions trigger various health issues related to overcrowding and WASH (water and sanitation, hygiene), the most important factor in the spread of infections. This is particularly true for the elderly population and the young.

The poor have limited access to health or other basic social services, like public transport. In dense settlements in major cities like Pasig, Mandaluyong, Quezon City, and Manila, looban communities deep in packed slums are accessible only by three-wheelers or habal-habal motorcycles that fit the narrow alleys.

Those with private vehicles are allowed to use them for urgent trips, but day laborers, frontline nurses, and poor dialysis patients reliant on public transport have been forced by the quarantine to walk for kilometers through multiple checkpoints. Everyone must now show a pass, whether one issued by the barangay government or the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID). This limits the ability of residents of poor communities to get food and urgent health care, making them more vulnerable to the spread of infection.

All of these create situations we’ve already seen, like ailing grandparents from the city’s slums braving checkpoints and possibly contracting COVID-19, to get food and medicine; otherwise, their children and grandchildren will starve to death. Once infections spread in these dense communities, it will be impossible to manage and contain.

Hot Spot: Quezon City

Quezon City is the largest and most populous city in the Philippines, home to over 2.9 million people living in 175.33 square kilometers.

Its large land area eases overall population density pressure. Based on 2015 data, Quezon City’s population density is at 17,759 residents per square kilometer. In contrast, eight of the other 15 cities in the National Capital Region surpassed the region’s average population density of 20,785 persons per square kilometer.

Table 2. Most Densely Populated Cities in Metro Manila

City | Population Density |

| 1. City of Manila | 71,263 persons per km2 |

| 2. Mandaluyong City | 41,580 persons per km2 |

| 3. Pasay City | 28,815 persons per km2 |

| 4. Caloocan City | 28,387 persons per km2 |

| 5. City of Navotas | 27,904 persons per km2 |

| 6. City of Makati | 27,010 persons per km2 |

| 7. City of Malabon | 23,267 persons per km2 |

| 8. City of Marikina | 20,945 persons per km2 |

Source: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015

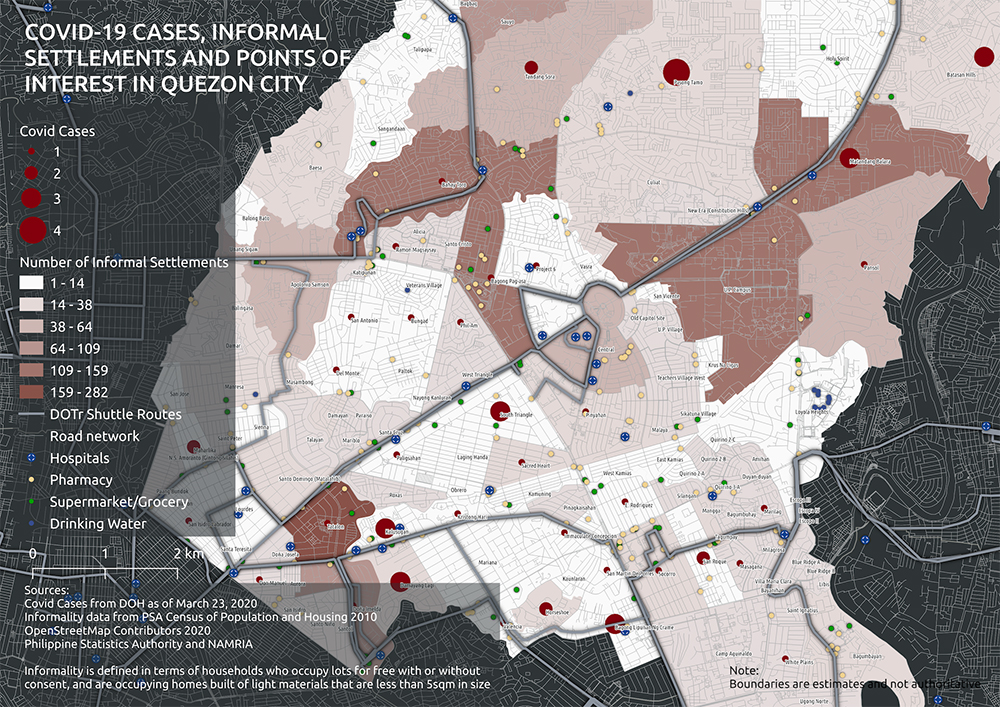

Although it is one of the least dense cities in Metro Manila, a 2015 analysis from the World Bank shows that more than a third of the total slums in the capital region can be found in Quezon City. The second ranking city, Taguig, hosts 10% of the total slum area of the region.

The largest clusters of the Quezon City slums are in Batasan Hills and Payatas, but informal settlements can be found in the borders of universities, beside affluent gated communities, and in the shadows of high-rise malls and high-end mixed-use developments, as in the case of Sitio San Roque. In these slums, daily-wage-dependent families do not always have access to water or soap. These families also do not have the luxury of space as they live in shanties too warm, packed, and uncomfortable to stay in for long periods of the day. This makes it impossible to follow the recommendations of the quarantine: social distancing of at least two meters between persons.

As of March 23, 42 of Quezon City’s 142 barangays have COVID-19 cases. Of these, 12 are under “extreme enhanced community quarantine.”

Table 3. Quezon City Barangays under Extreme Enhanced Community Quarantine

| District | Barangay |

| 1 | Maharlika Ramon Magsaysay San Isidro Labrador |

| 2 | Batasan Hills Bagong Silangan |

| 3 | Masagana |

| 4 | Damayang Lagi Kalusugan Tatalon Central* |

| 6 | Pasong Tamo |

Source: Quezon City Government, March 23, 2020

Note: Brgy. Central has no COVID-19 cases as of March 23, but has been placed under extreme quarantine due to its proximity to major hospitals.

According to the health department, there are 66 hospitals within Quezon City’s borders; 15 are government owned and 51 are private. Only 20 are categorized as Level 3 hospitals that have intensive care units, with some 7,500 beds.

Key hospitals serving COVID-19 cases include the Lung Center of the Philippines, which is one of the six hospitals in the country with testing capability and has dedicated one wing with 40 beds for COVID-19 patients; and the Philippine Heart Center, where over 20 health workers were exposed to the virus after a patient withheld travel information.

As of March 23, at least six doctors at the Heart Center have tested positive. Three have already died. At least 3 COVID-19 cases in Quezon City, with one from a congested urban poor community, have been sent home for lack of bedspace. Not all barangays have been able to set up isolation tents for the sick.

Note: The numbers of households in informal housing was calculated based on four variables from the 2010 census. First, we calculated the households who enjoy (a) rent-free occupation with consent of owner; and (b) rent-free without consent of owner. We then filtered those numbers based on the type of housing, specifically homes where (c) floor area is less than 5 square meters, and (d) whose outer walls are constructed of wood and other light materials.

The Department of Transportation and Office of the Vice President are running free bus services to bring health workers to hospitals, but many frontline workers live in different cities or have no access to “last-mile” transportation that can connect them from the pickup or transfer stations and back to their homes. Many nurses and other frontline medical personnel are forced to walk to work. A few have been able to obtain bicycles.

The maps also show locations of supermarkets and groceries, including major “bagsakan”’ consolidation markets like NEPA QMart and Balintawak Market. In the coming weeks, the lack of transport could endanger the food supply if produce deliveries are unable to enter the capital and if markets cannot operate at full capacity because their workers cannot report to work.

Farms and factories suffer from the same restrictions. Farmers from Cordillera, Laguna, Nueva Ecija, Cabanatuan, and Marinduque have taken to social media to warn that thousands of tons of produce are going to waste due to transport restrictions and the lack of markets to purchase the food.

What can be done—now!

We cannot arrest the contagion without coordinated efforts to address the problems of poverty, mobility, and food security among the poorest and neediest.

With the signing of Republic Act No. 11469 or the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act on March 24, the Executive Branch now has enhanced powers for the next three months to stem the tide of COVID-19 across the country.

For this to be effective, the national government needs to work with local governments, the private sector, and everyday citizens.

The first two weeks of the enhanced community quarantine have seen the private sector stepping up to provide assistance to frontliners and vulnerable communities. Big brands are donating their advertising budgets and securing support for their staff and suppliers. Private companies and citizens have begun to pledge support to fundraising initiatives.

These initiatives are also partnering with community-based organizations such as Caritas Manila and Samahan ng Nagkakaisang Pantawid Pamilya (SNPP) to reach families sorely affected by the lockdown.

Everyday citizens, including students, restaurant owners, and vendors alike, are donating what they can, including time, food, and bicycles for frontline workers. Citizen information drives such as @CureCovidPH and #PHCAN are now preparing information materials in vernacular languages for community use.

Many local government units have also begun distributing food packs to their barangays and have tapped into their Quick Response Funds to produce more in the coming weeks. But these efforts are not enough.

Old methods of emergency response no longer apply under the conditions of COVID-19. The checkpoints and other mobility restrictions mean that all efforts must be hyper localized, building on human resources and social capital within these respective cities for months to come.

These efforts should focus on:

1. Finding ways to increase community access to water and basic sanitation, particularly with increasing water shortages across the Philippines. Provide soap, hygiene kits, masks, and other basic supplies particularly in dense, deprived, and informal settlements across different cities.

a. Organize water rationing with the help of the Bureau of Fire Protection, Philippine Red Cross and other local volunteer organizations with water tanks.

b. Continue regular garbage collection and ramp up sanitation efforts across cities.

c. Set up sinks and handwashing stations in strategic common areas.

d. Repurpose clear plastic sheeting to serve as droplet shields for storefronts and other high-traffic areas.

e. Prepare methods for social distancing, quarantine, and care that uses the household and not the individual as the unit of care.

2. Providing support to the poorest families. Specifically, the civilian bureaucracy led by the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, Department of Social Welfare and Development and the Department of Labor and Employment, together with the Department of Transportation should implement, expand, and augment the existing social welfare programs to assist the affected labor force, marginalized, and other vulnerable sectors. Some of these programs include:

a. Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), Modified Conditional Cash Transfer Program (MCCT) for homeless street families, and Unconditional Cash Transfer (UCT) under DSWD. However, packages for families not included in Listahanan must also be considered.

b. PhilHealth, where coverage of all costs should be increased to include testing, consultation and hospitalisation related to COVID-19.

c. Pantawid Pasada (DOTR/LTFRB), which should be expanded to also cover other affected sectors such as tricycle, jeepney, bus, AUV, and taxi drivers

d. TUPAD (Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Disadvantaged /Displaced Workers) under the Department of Labor and Employment

3. Ensuring food security during the duration of the enhanced community quarantine.

a. The IATF-EID, Department of the Interior and Local Government, Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Trade and Industry must ensure that the strict quarantine guidelines will not disrupt the food supply chain. The DA assured the public that there is enough food for everyone. However, despite clear statements from national government that the delivery of food, agricultural products, and essential commodities should remain unimpeded, this has not been clearly applied across all local government units, many of which have installed their own checkpoints with varying interpretations of the rules established by the IATF-EID.

b. Local government units must start innovating in order to ensure that the people will have access to basic food necessities. Pasig City is presently implementing mobile markets to bring food closer to where people are, as is the Lanao del Sur provincial government. Mandaluyong is including fruits and vegetables in their food packs, while Baguio and Laguna are distributing vegetable seeds for ‘survival gardens’.

4. Ensuring that daily wage earners are not forced to leave their homes to feed their families by providing food aid and other incentives for the duration of the lockdown. The government must collaborate with private sector employers to assuage fears that they will lose their jobs if they are unable to physically report for work.

5. Supporting the mobility of frontline services and health workers, and ensuring that even citizens without private vehicles will have unimpeded access to health facilities, particularly those who are pregnant, undergoing dialysis or radiation, and in need of other essential health services. Options such as sanitized buses and bicycles can be provided for frontline workers.To the extent possible, provide options for temporary housing for front liners by coordinating with real estate developers, schools, and dormitories. Above all, efforts should be made to ensure that the implementation of checkpoint protocols are done in a humane, respectful, and non-arbitrary fashion, putting the health and safety of citizens first.

6. Supporting the health sector and local scientists to ramp up free testing capability across the Philippines, including for the poorest of the poor. With the absence of adequate laboratory facilities and trained personnel across the country, some of the PHP 27.1-billion package released by the Department of Finance should be channeled towards innovative solutions for addressing testing and the logistics thereof.

7. Sharing accurate and timely information both at the national and grassroots level, iand in local languages and channels. Consolidate communication channels for clear messaging and information dissemination and take advantage of existing communication platforms such as the government’s text alarms to provide more useful information, not just brief regular reminders to the public. Data sharing of anonymized information to protect patient privacy can also help in scientific and policy work in the long run.

8. Encouraging businesses to support the above mentioned efforts and coordinate with the government to create a singular, streamlined response.

9. Extending the deadline of tax collection in consideration of the logistical hurdles posed by the quarantine, and call on banks, businesses, and property owners to extend and/ or defer deadlines of bill and rental payments.

While these measures are focused on the experience of Metro Manila, quarantined communities in the rest of Luzon and in Visayas and Mindanao must also take steps to support the poorest and most vulnerable.

[Note: This is a popular version of a longer paper prepared by members of UrbanisMO, a group of urban planners and development professionals, in cooperation with the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. The papers in ENGLISH and TAGALOG are available on urbanismo.ph, facebook.com/urbanismoph, and twitter.com/urbanismodotph.]— PCIJ