By L.S. Mendizabal

(Trigger warning: Murders, mutilation of corpses)

“Pumarito ka. Bahala ka, kukunin ka ng aswang diyan! (Come here, or else the aswang will get you!)” is a threat often directed at Filipino children by their mothers. In fact, you can’t be Filipino without having heard it at least once in your life. For as early as in childhood, we are taught to fear creatures we’ve only seen in nightmares triggered by bedtime stories told by our Lolas.

In Philippine folklore, an “aswang” is a shape-shifting monster that roams in the night to prey on people or animals for survival. They may take a human form during the day. The concept of “monster” was first introduced to us in the 16th century by the Spanish to demonize animist shamans, known as “babaylan” and “asog,” in order to persuade Filipino natives to abandon their “anitos” (nature, ancestor spirits) and convert to Roman Catholicism—a colonizing tactic that proved to be effective from Luzon to Northern Mindanao.

In the early 1950s, seeing that Filipinos continued to be superstitious, the Central Intelligence Agency weaponized folklore against the Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon (Hukbalahap), an army of mostly local peasants who opposed US intervention in the country following our victory over the Japanese in World War II. The CIA trained the Philippine Army to butcher and puncture holes in the dead bodies of kidnapped Huk fighters to make them look like they were bitten and killed by an aswang. They would then pile these carcasses on the roadside where the townspeople could see them, spreading fear and terror in the countryside. Soon enough, people stopped sympathizing with and giving support to the Huks, frightened that the aswang might get them, too.

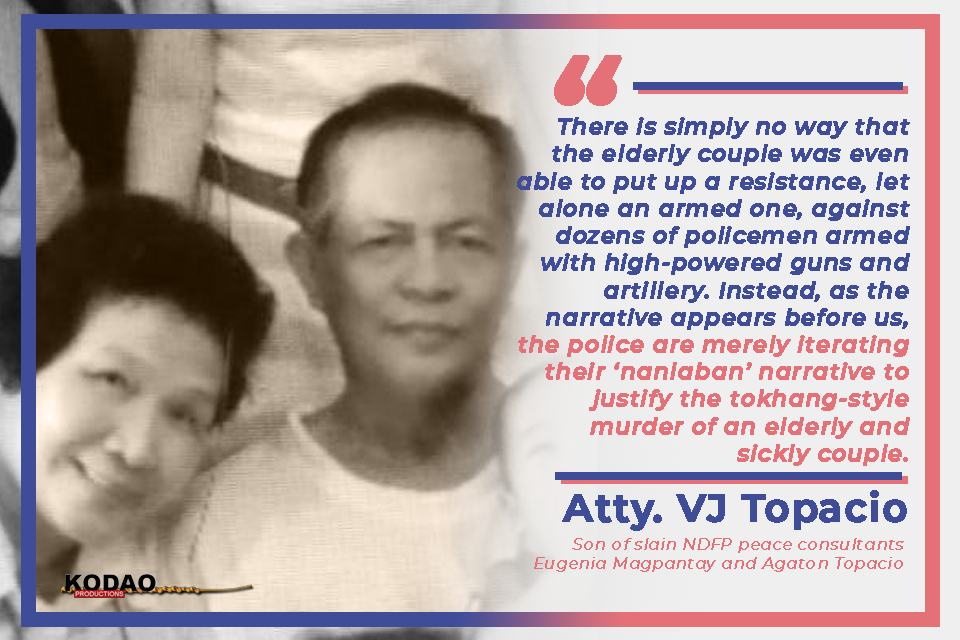

Fast forward to a post-Duterte Philippines wherein the sight of splayed corpses has become as common as of the huddled living bodies of beggars in the streets. Under the harsh, flickering streetlights, it’s difficult to tell the dead and the living apart. This is one of many disturbing images you may encounter in Alyx Ayn Arumpac’s Aswang. The documentary, which premiered online and streamed for free for a limited period last weekend, chronicles the first two years of President Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign on illegal drugs. “Oplan Tokhang” authorized the Philippine National Police to conduct a door-to-door manhunt of drug dealers and/or users. According to human rights groups, Tokhang has killed an estimated 30,000 Filipinos, most of whom were suspected small-time drug offenders without any actual charges filed against them. A pattern emerged of eerily identical police reports across cases: They were killed in a “neutralization” because they fought back (“nanlaban”) with a gun, which was the same rusty .38 caliber pistol repeatedly found along with packets of methamphetamine (“shabu”) near the bloodied corpses. When children and innocent people died during operations, PNP would call them “collateral damage.” Encouraged by Duterte himself, there were also vigilante killings too many to count. Some were gunned down by unidentified riding-in-tandem suspects, while some ended up as dead bodies wrapped in duct tape, maimed or accessorized with a piece of cardboard bearing the words, “Pusher ako, huwag tularan” (I’m a drug pusher, do not emulate). Almost all the dead casualties shared one thing in common: they were poor. Virtually no large-scale drug lord suffered the same fate they did.

And for a while, it was somehow tempting to call it “fate.” Filipinos were being desensitized to the sheer number of drug-related extrajudicial killings (a thousand a month, according to the film). “Nanlaban” jokes and memes circulated on Facebook and news of slain Tokhang victims were no longer news as their names and faces were reduced to figures in a death toll that saw no end.

As much as Aswang captures the real horrors and gore of the drug war, so has it shown effectively the abnormal “sense of normal” in the slums of Manila as residents deal with Tokhang on the daily. Fearing for their lives has become part of their routine along with making sure they have something to eat or slippers on their feet. This biting everyday reality is highlighted by Arumpac’s storytelling unlike that of any documentary I’ve ever seen. Outlined by poetic narration with an ominous tone that sounds like a legitimately hair-raising ghost story, Aswang transports the audience, whether they like it or not, from previously seeing Tokhang exclusively on the news to the actual scenes of the crime and funerals through the eyes of four main individuals: a nightcrawler photojournalist and dear family friend, Ciriaco Santiago III (“Brother Jun” to many), a funeral parlor operator, a street kid and an unnamed woman.

Along with other nightcrawlers, Bro. Jun waits for calls or texts alerting them of Tokhang killings all over Manila’s nooks and crannies. What sets him apart from the others, perhaps motivated by his mission as Redemptorist Brother, is that he speaks to the families of the murdered victims to not only obtain information but to comfort them. In fact, Bro. Jun rarely speaks throughout the film. Most of the time, he’s just listening, his brows furrowed with visible concern and empathy. It’s as if the bereaved are confessing to him not their own transgressions but those committed against them by the state. One particular scene that really struck me is when he consoles a middle-aged man whose brother was just killed not far from his house. “Kay Duterte ako pero mali ang ginawa nila sa kapatid ko” (I am for Duterte but what they did to my brother was wrong), he says to Bro. Jun in between sobs. Meanwhile, a mother tells the story of how her teenage son went out with friends and never came home. His corpse later surfaced in a mortuary. “Just because Duterte gave [cops] the right to kill, some of them take advantage because they know there won’t be consequences,” she angrily says in Filipino before wailing in pain while showing Bro. Jun photos of her son smiling in selfies and then laying pale and lifeless at the morgue.

The Eusebio Funeral Services is a setting in the film that becomes as familiar as the blood-soaked alleys of the city. Its operator is an old man who gives the impression of being seasoned in his profession. And yet, nothing has prepared him for the burden of accommodating at least five cadavers every night when he was used to only one to two a week. When asked where all the unclaimed bodies go, he casually answers, “mass burial.” We later find out at the local cemetery that “mass burial” is the stacking of corpses in tiny niches they designated for the nameless and kinless. Children pause in their games as they look on at this crude interment, after which a man seals the niche with hollow blocks and wet cement, ready to be smashed open again for the next occupant/s. At night, the same cemetery transforms into a shelter for the homeless whose blanketed bodies resemble those covered in cloth at Eusebio Funeral Services.

“Tama na po, may exam pa ako bukas” (Please stop, I still have an exam tomorrow). 17-year-old high school student, Kian Delo Santos, pleaded for his life with these words before police shot him dead in a dark alley near his home. The documentary takes us to this very alley without the foreknowledge that the corpse we see on the screen is in fact Kian’s. At his wake, we meet Jomari, a little boy who looks not older than seven but talks like a grown man. He fondly recalls Kian as a kind friend, short of saying that there was no way he could’ve been involved in drugs. Jomari should know, his parents are both in jail for using and peddling drugs. At a very young age, he knows that the cops are the enemy and that he must run at the first sign of them. Coupled with this wisdom and prematurely heightened sense of self-preservation is Jomari’s innocence, glimpses of which we see when he’s thrilled to try on new clothes and when he plays with his friends. Children in the slums are innocent but not naïve. They play with wild abandon but their exchanges are riddled with expletives, drugs and violence. They even reenact a Tokhang scene where the cops beat up and shoot a victim.

Towards the end of the film, a woman whose face is hidden and identity kept private gives a brief interview where, like the children drawing monsters only they could see in horror movies, she sketches a prison cell she was held in behind a bookshelf. Her interview alternates with shots of the actual secret jail that was uncovered by the press in a police station in Tondo in 2017. “Naghuhugas lang po ako ng pinggan n’ung kinuha nila ‘ko!” (I was just washing the dishes when they took me!), screams one woman the very second the bookshelf is slid open like a door. Camera lights reveal the hidden cell to be no wider than a corridor with no window, light or ventilation. More than ten people are inside. They later tell the media that they were abducted and have been detained for a week without cases filed against them, let alone a police blotter. They slept in their own shit and urine, were tortured and electrocuted by the cops, and told that they’d only be released if they paid the PNP money ranging from 10 000 to 100 000 pesos. Instead of being freed that day, their papers are processed for their transfer to different jails.

Aswang is almost surreal in its depiction of social realities. It is spellbinding yet deeply disturbing in both content and form. Its extremely violent visuals and hopelessly bleak scenes are eclipsed by its more delicate moments: Bro. Jun praying quietly by his lonesome after a night of pursuing trails of blood, Jomari clapping his hands in joyful glee as he becomes the owner of a new pair of slippers, an old woman playing with her pet dog in an urban poor community, a huge rally where protesters demand justice for all the victims of EJKs and human rights violations, meaning that they were not forgotten. It’s also interesting to note that while the film covers events in a span of two years, the recounting of these incidents is not chronological as seen in Bro. Jun’s changing haircuts and in Jomari’s unchanging outfit from when he gets new slippers to when he’s found after months of going missing. Without naming people, places and even dates, with Arumpacletting the poor do most of the heavy lifting bysimply telling their stories on state terrorism and impunity in their own language, Aswang succeeds in demonstrating how Duterte’s war on drugs is, in reality, a genocide of the poor, elevating the film beyond numb reportage meant to merely inform the public to being a testament to the people’s struggle. The scattered sequence, riveting images, sinister music and writing that borrows elements from folklore and the horror genre make Aswang feel more like a dream than a documentary—a nightmare, to be precise. And then, a rude awakening. The film compels us to replay and review Oplan Tokhang by bringing the audience to a place of such intimate and troubling closeness with the dead and the living they had left behind.

Its unfiltered rawness makes Aswang a challenging yet crucial watch. Blogger and company CEO, Cecile Zamora, wrote on her Instagram stories that she only checked Aswang out since it was trending but that she gave up 23 minutes in because it depressed her, declaring the documentary “not worth her mental health” and discouraging her 52,000 followers from watching it, too. Naturally, her tone-deaf statements went viral on Twitter and in response to the backlash, she posted a photo of a Tokhang victim’s family with a caption that said she bought them a meal and gave them money as if this should exempt her from criticism and earn her an ally cookie, instead.

Aswang is definitely not a film about privileged Filipinos like Zamora—who owns designer handbags and lives in a luxurious Ed Calma home—but this doesn’t make the documentary any less relevant or necessary for them to watch. Zamora missed the point entirely: Aswang is supposed to make her and the rest of us feel upset! It nails the purpose of art in comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comfortable. It establishes that the only aswang that exists is not a precolonial shaman or a shape-shifting monster, but fear itself—the fear that dwells within us that is currently aggravated and used by a fascist state to force us into quiet submission and apathy towards the most marginalized sectors of society.

Before the credits roll, the film verbalizes its call to action in the midst of the ongoing slaughter of the poor and psychological warfare by the Duterte regime:

“Kapag sinabi nilang may aswang, ang gusto talaga nilang sabihin ay, ‘Matakot ka.’ Itong lungsod na napiling tambakan ng katawan ay lalamunin ka, tulad ng kung paano nilalamon ng takot ang tatag. Pero meron pa ring hindi natatakot at nagagawang harapin ang halimaw. Dito nagsisimula.” (When they say there’s a monster, what they really want to say is “be afraid.” This city, chosen to be the dumpsite of the dead, will devour you as fear devours courage. But there are still those who are not afraid and are able to look the monster in the eye. This is where it begins).

During these times, when an unjust congressional vote recently shut down arguably the country’s largest multimedia network in an effort to stifle press freedom and when the Anti-Terrorism Law is now in effect, Aswang should be made more accessible to the masses because it truly is a must-see for every Filipino, and by “must-see,” I mean, “Don’t you dare look away.” #

= = = = = =

References:

Buan, L. (2020). “UN Report: Documents suggest PH Police Planted Guns in Drug War Ops”. Rappler. Retrieved from https://rappler.com/nation/united-nations-report-documents-suggest-philippine-police-planted-guns-drug-war-operations

Ichimura, A., & Severino, A. (2019). “How the CIA Used the Aswang to Win a War in the Philippines”. Esquire. Retrieved from https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/cia-aswang-war-a00304-a2416-20191019-lfrm

Lim, B. C. (2015). “Queer Aswang Transmedia: Folklore as Camp”. Kritika Kultura, 24. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3mj1k076

Tan, L. (2017). “Duterte Encourages Vigilante Killings, Tolerates Police Modus – Human Rights Watch”. CNN Philippines. Retrieved from https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2017/03/02/Duterte-PNP-war-on-drugs-Human-Rights-Watch.html