‘The wastewater looked like mud’: EMB goes after Vitarich Corp.

Four reporting fellows of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) took a motorized boat to Marilao River to search for the outfall pipes of the town’s biggest chicken dressing plant. It wasn’t easy.

BY ANNIE RUTH SABANGAN, BERNARDINO TESTA, ROBERT JA BASILIO JR. AND RIC PUOD

Part 2 of 4

Read Part 1: The Bulacan town where chickens are slaughtered and the river is dead

What you need to know about Part 2:

- A PCIJ team sails into Sapang Alat, a creek where Marilao’s biggest chicken dressing plant releases wastewater, and discovers how the water has turned into a garbage dump.

- While the Municipal Health Office has the mandate to go after pollutive industries, it has not been able to exercise its powers.

- A closure order from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ Environmental Management Bureau finally prompted the operators of the dressing and rendering facilities of Vitarich Corporation to take action, but an environmental officer thinks the solution is unsustainable.

It was a rainy Tuesday and it was high tide at the Marilao River. On Sept. 24, 2019, when the coronavirus pandemic was still months away, a PCIJ team took a motorized outrigger boat into the river and embarked on a search for the waste pipe of a poultry processing plant.

The brown liquid waste that flowed from pipes jutting from the compound of Vitarich Corp., one of the country’s biggest poultry and feed firms, was visible from a window of the Municipal Health Office (MHO) of Marilao. Getting to its location in Sapang Alat (Salty Creek) wasn’t so easy, however.

It was near impossible to wade through the sludge on the river bed. The team rented a boat in Brgy. Poblacion and sailed to the creek, a tributary of the Marilao River, and waited for high tide because otherwise the boat would be stuck in the shallow and rocky parts of the waterway.

Marlo (not his real name), a fisherman who served as guide, knew the river like the palm of his hands; but the search would still turn out to be arduous. The waters were still, but the boat had to stop at least five times. Occasionally, Marlo had to reach into the putrid water with his bare hands to weed out the trash caught by the boat’s propeller.

“Baka hindi sa lunod ako mamamatay nito, baka sa dumi at baho (I will not die here because of drowning, but because of filth and stink),” quipped one of the team members.

It was almost one hour of this before the team reached the bridge at the mouth of the creek, where the water turned visibly foamy from the viscous effluents coming from drain pipes lining the riverside. The water body had been abused like this by residents and businesses alike, although some are more responsible for its death than others.

It should have been a warning of what awaited the PCIJ team inside Sapang Alat, but the members were not prepared for what they saw when Marlo shut down the motor of the boat and turned the outrigger towards an inlet that leads to the creek.

It was a garbage dump. The water turned a darker color, thicker, and filthier from a mix of solid and liquid waste. Marlo had to use a bamboo pole to propel the boat, which often got stuck in mounds of trash.

Dead fish floated on the water. A rotting tilapia was discolored and its eyes were missing. A disfigured janitor fish –– bloodied, bloated and burnt –– looked monstrous with its teeth exposed.

“Siguro napadpad sila dito, inanod noong nag-high tide. Patay na ‘tong sapa na ‘to e, wala nang mabubuhay na isda rito (Maybe they were carried here by the waters when it was high tide. This stream is dead. No fish will survive here),” Marlo said.

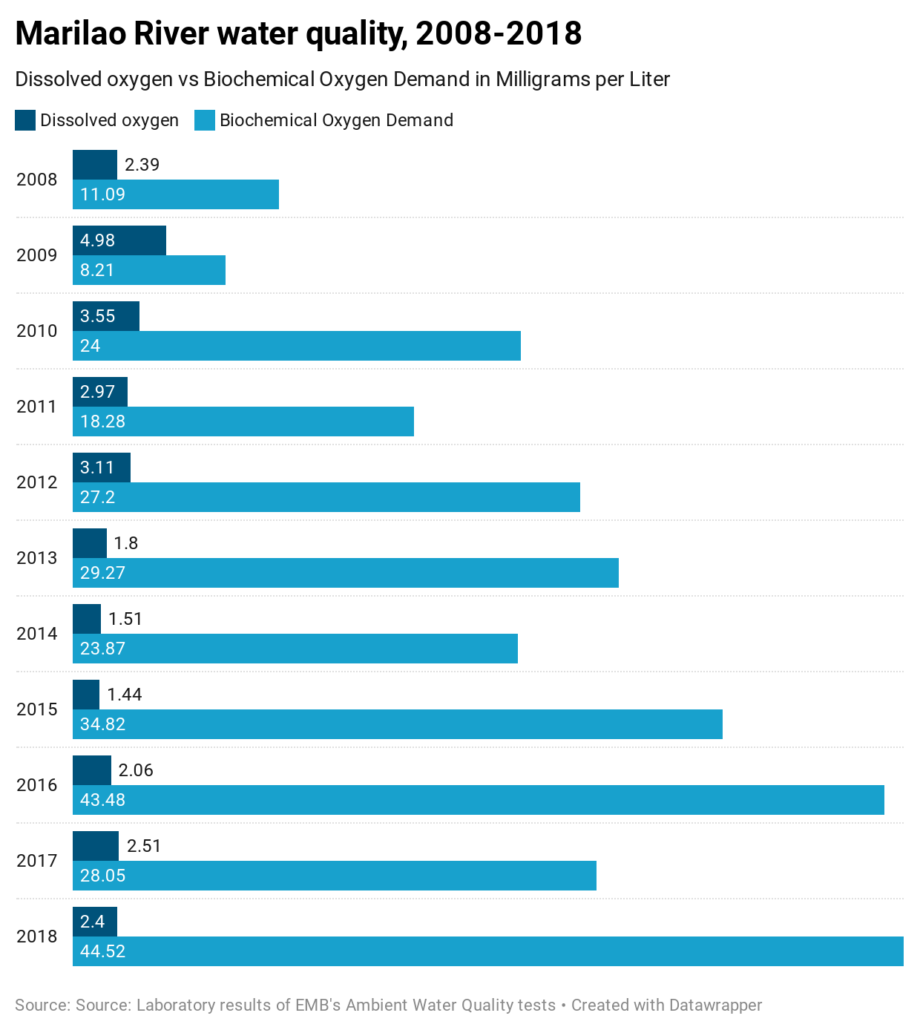

Glenn Aguilar, who monitors the river as staff of the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) Region 3 office of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), linked the fish’s death to the absence of oxygen in the waters.

“It’s an indication na patay na ‘yung tubig…Ang isda hindi siya mabubuhay kung walang oxygen (It’s an indication that the river is dead…. The fish can’t survive without oxygen),” Aguilar said in an interview later.

While the janitor fish is known to live and multiply even in polluted waters, Aguilar said it’s not capable of surviving in dead waters for a long time.

The team also found a big plastic bag filled with creamy matter floating on the water. A stomach-turning smell was released when the receptacle was opened. It contained decaying chicken entrails.

This part of the creek was flecked with a brownish and yellowish substance smelling like poultry feces, too.

The boat continued to follow the creek’s meandering course upstream, towards Vitarich Corporation’s outfall pipes. There was a place where trees grew and wild weeds crawled on the banks of the creek. One large tree was bedecked with dirty plastic trash. Here, where there was thick vegetation, bubbles of air rose from the water and made for an eerie atmosphere.

Finally, the sound of water rushing like a waterfall was heard. There it was –– the outfall pipe from the compound of Vitarich Corp. The team collected water samples.

The PCIJ team would later learn from the EMB and the Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Office (MENRO) that the pipe wasn’t from the dressing plant itself, but from the feather rendering facility that converts feathers of slaughtered poultry into animal feed ingredients. It was operated by PSP Aqua Resources, a business partner of Vitarich Corp.

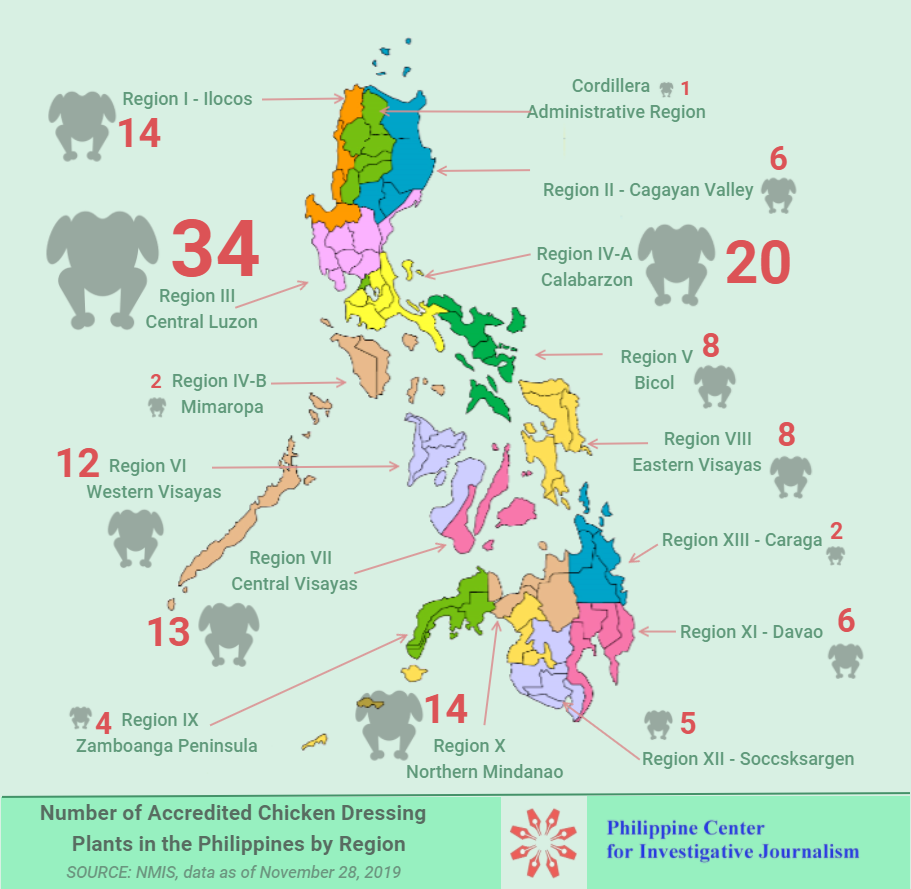

The PCIJ team would take another boat trip the following month, in October 2019, to Sapang Alat to collect more water samples. The team also set off to search for the drain pipes of other poultry processing plants in Brgy. Loma De Gato.

Cease-and-desist order

Eight months earlier, on Jan. 24, 2019, the EMB Region 3 office ordered two plants inside the compound of Vitarich Corporation to “cease and desist” from releasing wastewater into Sapang Alat.

EMB said the dressing and rendering plants –– operated by Alt Trading and PSP Aqua Resources, respectively –– did not have discharge permits.

In two separate but identical violation notices, then EMB Region 3 Director Lormelyn Claudio said their treatment facilities were “not properly operated and [were] therefore discharging untreated wastewater,” which was a violation of the Clean Water Act.

Three days after the cease and desist order was issued, on Jan. 27, Marilao’s environment officer Reynaldo Buenaventura accompanied EMB pollution inspectors to Sapang Alat to seal a canal that dumped wastewater from one of the Vitarich plants into the Marilao River.

It was part of the national government’s efforts to clean up Manila Bay. On the same day, DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu declared from the Baywalk in the country’s capital the start of the rehabilitation of the bay.

Marilao River is part of Meycuayan-Marilao-Obando River System that dumps wastes into the bay.

“Ang tubig parang hindi na liquid e… Parang lupa na. Ibig sabihin hindi na umaagos…. Nagso-solid na e (The water no longer looked like it was liquid. It looked like mud. It means it’s no longer flowing…it has solidified),” Buenaventura told PCIJ.

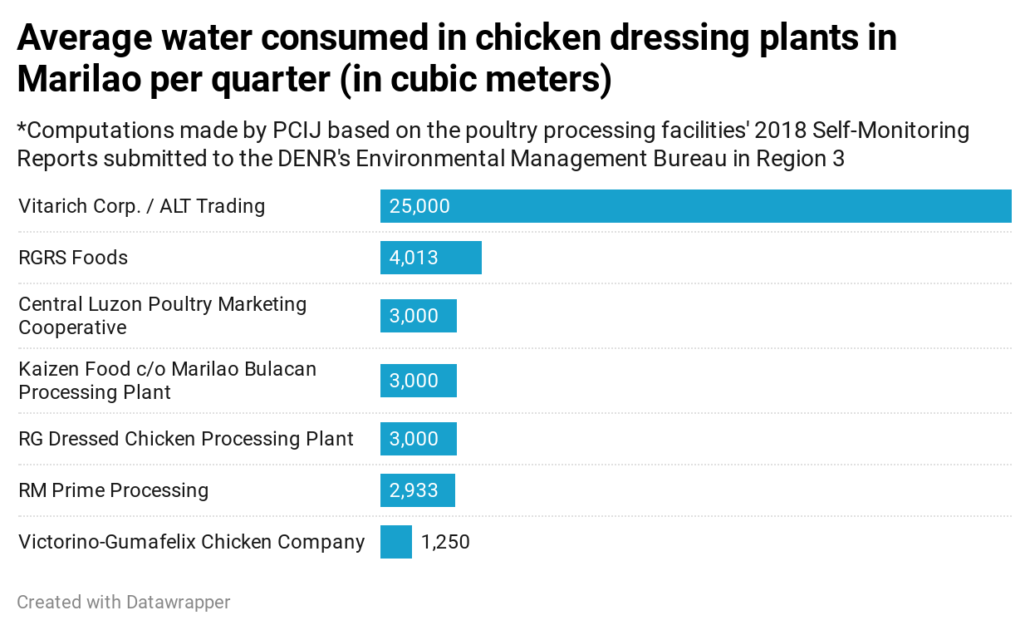

Water sampling analyses conducted by the EMB showed that the plants’ wastewater discharges exceeded effluent limits. The polishing ponds –– which were supposed to improve the quality of the effluents before it was released into the river–– were no longer capable of cleansing wastewater at that time, according to Climaco Jurado of EMB Region 3’s Environment Monitoring and Enforcement Division.

The violation notices barred the plants from resuming operations until the issues were rectified.

Vitarich sought to distance itself from the violation notices issued against the dressing and rendering plants inside its compound. While the company owned the two plants in question, Vitarich lawyer Mary Christine Dabu-Pepito told PCIJ that the plants were operated by its business partners.

“They are in the best position to answer whether these violations indeed occur and what were the steps they undertook to address the issues raised in the NOVs,” she said in a May 12, 2020 e-mail responding to PCIJ’s questions.

“At any rate, Vitarich requires its business partners to operate within the bounds of law, including compliance with environmental laws and regulations,” she said.

Ramiro Osorio, officer in charge of the EMB’s legal office, disagreed. In an interview on Aug. 8, 2020, Osorio said Vitarich also bore responsibility because the company is the project proponent and holder of the environmental compliance certificates (ECC), issued to the rendering facility in October 1997 and the dressing plant in October 2008.

The ECC “is a project-specific permit” that makes the proponent directly responsible for the project, he said.

Copies of the two 2019 stop orders obtained by the PCIJ from EMB-Region 3 showed that they were addressed to the president of Vitarich Corp., the operations manager of PSP Aqua, and the manager of Alt Trading.

“Wala pong pakialam ang DENR do’n kung sino ang nag-o-operate ng rendering plant. Kung sino ang nakapangalan sa ECC, sila ang ire-regulate namin (The DENR isn’t concerned with who operates the rendering plant. Whoever is named in the ECC is the entity we will regulate),” said Osorio.

Source of wastewater discharge

Eduardo Lazo –– an executive at both the chicken dressing and rendering plants –– said they did not secure a permit to discharge because the rendering facility was not supposed to have effluents.

What happened was that wastewater from the dressing facility overflowed, he said, carrying chicken feathers from the rendering plant into a drainpipe. He maintained that the rendering plant did not release wastewater. To address this problem, he said PSP Aqua installed a separate pipe to catch raw feather materials and redirect them to a digestive chamber.

“The feathers must first be filtered out of water. Then the wastewater from it will pass through the dressing plant’s wastewater treatment facility. So wala na kaming discharge (So we no longer have a discharge),” he said.

Lazo said the discharge that PCIJ found gushing at the back of the Vitarich compound in September 2019 did not come from the rendering plant but from the ice plant that was also located within the premises.

Does the ice plant need a discharge permit from the EMB? “I don’t think so…Ano ito e, tubig na malinis na galing sa pinagtabasan ng yelo (It’s just clean water that comes from ice cuttings),” said Lazo, referring to the effluent.

The wastewater samples collected by the PCIJ were warm.

EMB-Region 3’s Jurado, who inspected the rendering facility in January 2019, rejected Lazo’s claim. In an interview on Oct. 14, 2019, Jurado said PSP Aqua was issued a CDO because it was “discharging without discharge permit.”

“Kasi ang claim nila wala silang discharge kasi naka-line lang sila sa dressing plant. E noong pag-inspection namin, meron silang sariling wastewater discharge. Nakita talaga namin (ang) pipe galing sa kanila (Their claim was that they didn’t have a discharge because they were linked to the dressing plant’s wastewater treatment system. But when we inspected the facility, we found out that they had their own wastewater discharge. We really saw that they had their own pipe),” Jurado said.

“Wala silang polishing pond (They didn’t have a polishing pond),” he added, referring to PSP Aqua’s lack of treatment facility for its own wastewater.

MENRO’s environmental management specialist Dan Ezekiel Martin, who also inspected the rendering plant before the CDO was issued, also said that PSP Aqua had its own wastewater discharge.

Jurado said PSP Aqua fixed the problem after it “re-channeled” its pipe to the dressing plant’s wastewater treatment facility.

Dressing plant’s wastewater treatment system overhauled

In October 2019, the EMB’s Environment Monitoring and Enforcement Division recommended the lifting of the CDO after the dressing and rendering plants rectified issues raised.

It was around the time the PCIJ team made its second visit to Sapang Alat and, by then, the effluents were no longer spilling out as a result of the CDO.

Records from the Marilao government showed that the improvements coincided with the entry of a new business partner –– Barbatos Ventures Corp. –– to replace Alt Trading as Vitarich’s business partner to operate the dressing plant. Barbatos was granted a government sanitary permit on July 12, 2019.

The EMB also recognized the efforts to fix the treatment facility of the dressing plant, according to Glenn Aguilar of EMB-Region 3. “[I]naayos muna nila ‘yong treatment facility…. Pabalik-balik sila dito sa amin, pinapakita ‘yung [lab] results ng [wastewater] sampling nila (They fixed the treatment facility first…. They were here several times to show the lab results of their wastewater samples),” Aguilar told the PCIJ in an interview on Oct. 28, 2019.

Lazo said Alt Trading complied with the EMB requirements. “The CDO was given to Alt Trading and they were able to fully comply,” Lazo told PCIJ during a July 21, 2020 interview. He was referring to the conditions set by the EMB, which included treating the effluent from the chicken dressing facility so that it could conform to the government’s wastewater quality standards.

Lazo said Barbatos also started a P6.1-million project, composed of a three-phase process, to overhaul the dressing plant’s wastewater treatment system. He said Barbatos knew that treating the facility’s wastewater wouldn’t be enough and an overhaul was needed as grass had grown on the pond and one could walk on the hardened scum., Phase 1, worth P2.3 million, included the installation of polyethylene liners on all five of the dressing plant’s treatment ponds to prevent the seepage of wastewater.

Phase 2 involved the placement of floating aerators on three of the five ponds, which was worth P2 million.

Phase 3, which was in the pipeline at the time of Lazo’s interview with PCIJ in July 2020, would be the installation of a water clarifier and filtration system that would cost P1.8 million.

“When the system is in place, only clear water will come out of the last two ponds,” Lazo said.

In a June 2, 2020 report, the Marilao government’s Joint Inspection Team (JIT) noted improvements in the dressing plant’s wastewater treatment facility. The discharge was clean and no longer smelly, according to the report signed by Buenaventura and business licensing head Martin Armando Cruz.

Lazo welcomed the results of the JIT inspection and said the “ultimate objective” of Barbatos was “to no longer need a permit from the DENR to discharge wastewater.”

“That’s because we will no longer generate wastewater. We will be able to recycle all the water we use,” he said.

This remains to be seen, however. Dan Ezekiel Martin, the MENRO’s environmental management specialist who inspected Vitarich’s dressing facility with EMB staffers in 2019, saw a bigger sustainability challenge.

Production in the dressing plant kept increasing, but the size of the area for wastewater treatment remained the same, he said.

“Kasi normally, sa gano’n kalaking dressing plant…dapat hectares ang usapan ng laki ng area ng [wastewater treatment] pond (Because normally in a dressing plant as big as that…we should be talking in terms of hectares of wastewater treatment pond),” Martin told the PCIJ in an interview in September 2019, noting that there were only five waste stabilization ponds in the facility.

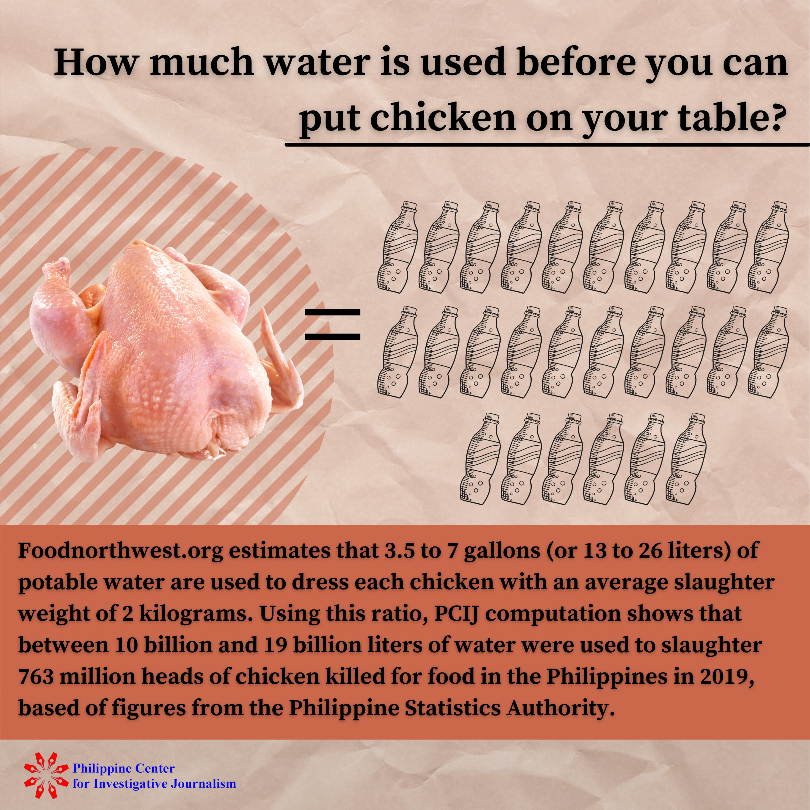

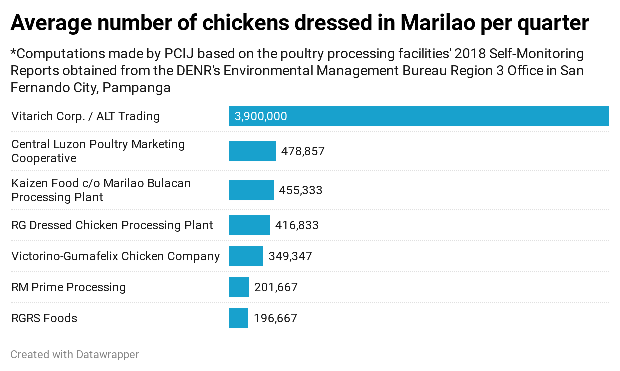

As of 2018, the production capacity of the dressing plant was 50,000 a day or 1.2 million birds a month, based on the self-monitoring report (SMR) submitted by Alt Trading. It was over three times its production capacity a decade earlier, in 2008, when it had an output of only 15,000 birds a day.

Stench lingers

Despite the interventions, however, Lazo admitted the facility would continue to stink.

“Kasi…hindi mo puwedeng sabihin na 100% mawawala ang amoy, kasi you’re dealing here with waste. Iyong raw feathers may malansang amoy na ‘yan kasi (You can’t say that the odor will be gone 100% because you are dealing here with waste. The raw feathers already have a fishy smell),” Lazo said.

Lazo claimed that the rendering plant was necessary because it solved Marilao’s waste disposal problem.

“If, say, Marilao dresses 300,000 chickens a day, that means producing 30 tons of feather waste daily if you don’t have a rendering plant…. No dumpsite will accept that huge volume of waste. It’s a high-maintenance waste. You have to bury it and address the odor. Decaying feathers smell like dead humans,” he said.

Like hair, chicken feathers are made up of fibrous protein called keratin that is resistant to being biodegraded or decomposed by bacteria, he explained.

The Business Permits and Licensing Office (BPLO) shared Lazo’s position. BPLO chief Amado Cruz said Vitarich’s rendering plant also collected chicken feathers from other dressing plants in the town and helped address poultry waste disposal in Marilao and the entire Bulacan province.

“Kasi…kung itatapon mo itong feather sa basurahan or sa isang sanitary land facility, mapupuno tayo sa dami ng residual feather…kung walang centralized na rendering plant dito sa Vitarich (We would all be swamped with feathers if you threw these in the trash can or in a sanitary land facility and…if there’s no centralized rendering plant in Vitarich),” he said, stressing that feathers don’t decompose easily in a landfill.

“Sanay na ang mga tao dito sa amoy…. Alam nila ‘yung nature ng business kaya alam din nila pag ‘yun pinasara, mawawalan ng workers (The residents are used to the smell…. They know the nature of the business that’s why they also know that if it would be closed, there would be no more workers),” he added. — PCIJ, February 2021

This series was produced with the support of Greenpeace Southeast Asia — Philippines.

Next: Poultry processing plants responsible for the pollution of Marilao River have gotten away with small fines.— PCIJ