Position Paper on the proposed amendments to the Human Security Act of 2017 (House Bills 7141 and 5507)

Your Honors:

Following is a more complete version of NUJP’s position paper delivered during the Technical Working Group (TWG) meeting of June 18, 2018.

The NUJP opposes these bills, as well as the working draft currently being discussed by the TWG, asthey include provisions that may be later used against the people’s right to freedom of expression and the freedom of the press. If passed and implemented, this will make the practice of journalism in this country impossible and extremely dangerous.

Specifically:

- Section 4, wherein Republic Act 10175, otherwise known as the Cybercrime Law, specifically its Chapter II, item 4 on Libel, is included as a predicate crime on terrorism.

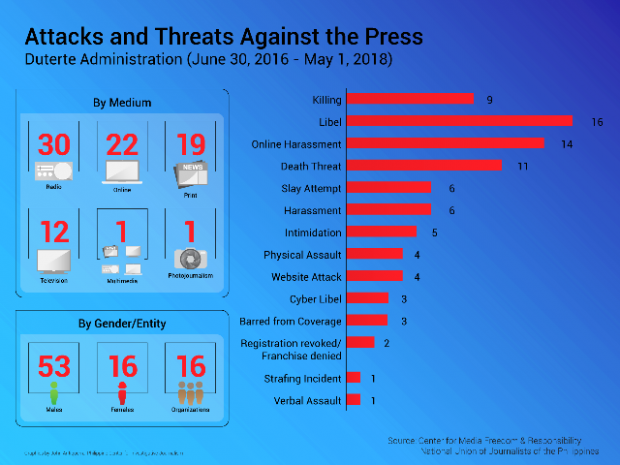

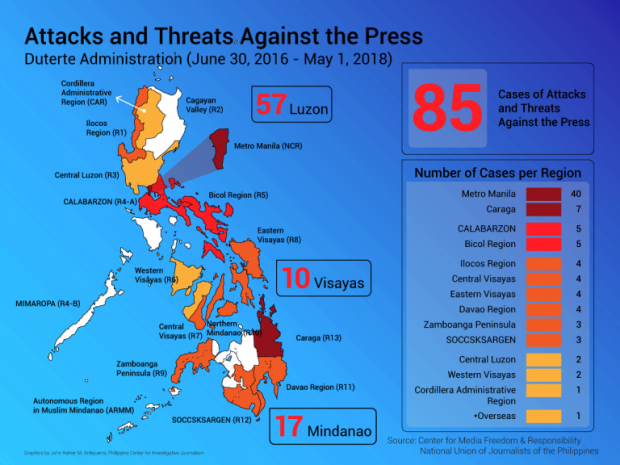

The NUJP and the mass media industry in general is on record to be opposed to libel as a crime, as it in fact being used to harass journalists. We have petitioned congress to decriminalize libel, as we are on record to have opposed the Cybercrime Law. We surely cannot agree to making libel an even stronger law by making it a predicate crime for the crime of terrorism.

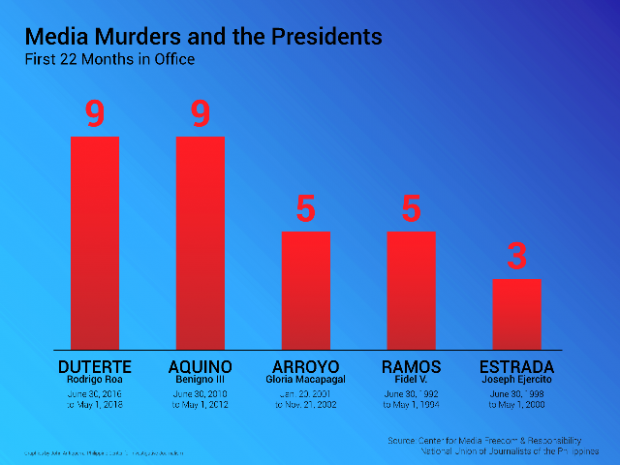

In addition, almost all media outfits nowadays have online platforms. The inclusion of the Cybercrime Law as a predicate crime to the crime of terrorism would endanger journalists the most. We fear critical reports and opinion may already be called terroristic acts. Why pass bills that may constrict the exercise of free journalism in this country when, in fact and in practice, it is increasingly being subverted already? May we remind the TWG that according to our Constitution, “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of the press.”

- Section 5(b). Inciting to terrorism. – Any person who incites another person by any means to commit terrorism whether or not directly advocating the commission of any of such act, thereby causing danger that one or more such acts may be committed, shall be punished with the penalty of life imprisonment.

(We note that the National Bureau of Investigation and the Anti-Money Laundering Council propose that the words “inciting to terrorism” be defined and that the NBI has said that the penalty of life imprisonment is excessive and places inciters at the same level as those who actually commit terrorism. On the basis of the gravity of offense, inciting to terrorism warrants a lighter penalty.)

We ask, who determines incitement? Would a news article explaining the roots of “terrorism” or rebellion, which terms the government often interchanges freely, qualify as incitement? Past governments certainly viewed it this way.

- Sec. 5 (f). Glorification of terrorism – Any person who, not being a conspirator, accomplice or accessory under Sections 5, 6 and 7 of this act, shall by any means make a statement or act, through any medium, which tends to directly or indirectly encourage, justify, honor or otherwise induce the commission of terrorist acts (as proposed by the department of defense) by proscribed or designated individuals or organizations, or shall by any means honor glorify proscribed or designated individuals or organizations (as proposed by the AMLC), shall suffer the penalty of ten (10) years of imprisonment.

We offer the same comment as above. Who determines glorification and terrorism? Might not this provision be used by state forces to charge and harass members of the press who would write something about so called terrorism, misconstruing such as glorification?

- Sec. 5(g). Membership in terrorist organizations. – Any person who shall knowingly become a member or manifest his/her intention to become a member of any Philippine Court-proscribed or United Nations Security Council-designated terrorist organization shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment.” (House Bill No. 5507)

The government, particularly state security forces, have time and again tagged legal organizations, including the NUJP, as “fronts” or even “enemies of the state.” If these agencies have been so cavalier in endangering the lives and reputation of legitimate media organizations in the past, these bills would further embolden them to violate our rights.

- Sec. 9. Section 8 of the same act is hereby renumbered and amended to read as follows:

“Section[8] 9. Formal application for judicial authorization. – The written order of the authorizing division of the court of appeals and/or regional trial court.

(The Philippine Military Academy Alumni Association – Eagle Chapter proposes to change the references to Court of Appeals and RTC to “proper judicial authorities” and the phrase “probable cause based on personal knowledge” to “probable cause based on reasonable ground of suspicion of facts and circumstances.”)

To track down, tap, listen to, intercept, and record communications, messages, conversations, discussions, or spoken or written words [of any person suspected of the crime of terrorism or the crime of conspiracy to commit terrorism] in Section 8 hereof shall only be granted by the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals and/or the Regional Trial Court upon an ex parte written application of a [police or of a law enforcement official] law enforcement or military personnel [who has been duly authorized in writing by the anti-terrorism council created in sec. 53 of this act to file such ex parte application], and upon examination under oath or affirmation of the applicant and [the] his/her witnesses [he may produce to establish]: (a) that there is probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that any of the [said] crimes [of terrorism or conspiracy to commit terrorism] in section 4, 5, 5(a), 5(b), 5(c), 5(d), 5(e), 5 (f) and 5(g) hereof [has] have been committed, or [is] are being committed, or [is] are about to be committed; (b) that there is probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that evidence, which is essential to the conviction of any charged or suspected person for, or to the solution or prevention of, any such crimes, will be obtained; and, (c) that there is no other effective means readily available for acquiring such evidence.

(On the phrases “In case of imminent danger or actual terrorist attack,” we note that the Department of Information and Communications Technology proposes to define the terms “imminent danger” and “actual terrorist attack.)

The Secretary of the Department of Information and Communications Technology / National Telecommunications Commission (as proposed by the DOJ) the Court of Appeals or the Regional Trial Court, upon the certification of the Anti-Terrorism Council based on reasonable ground of suspicion on the part of the law enforcement or military personnel, (as proposed by the Philippine National Police) shall have the power to compel telecom and internet service providers to produce all customer information and identification records as well as call and text data records and other cellular or internet metadata of any person suspected of any crime in section 4, 5, 5(a), 5(b), 5(c), 5(d), 5(e), 5(f) and 5(g) hereof.

Again, Your Honors, this is dangerous. It would open the floodgates to a widespread violation of people’s rights, including journalists. Also, if the proposals of Philippine Military Academy Alumni Association–Eagle Chapter to change the references to Court of Appeals and RTC to “proper judicial authorities” and the phrase “probable cause based on personal knowledge” to “probable cause based on reasonable ground of suspicion of facts and circumstances” are adopted, this could expose practically anyone to invasion of privacy.

- Section 18. Period of detention without judicial warrant of arrest. – The provisions of Article 125 of the Revised Penal Code to the contrary notwithstanding, any [police or] law enforcement or military personnel [, who, having been duly authorized in writing by the Anti-Terrorism Council] has taken custody of a person [charged with or] suspected [of the crime of terrorism or the crime of conspiracy to commit terrorism]of committing any of the punishable acts in section 4, 5(a), 5(b), 5(c), 5(d), 5(e), 5(f) and 5(g) hereof shall, without incurring any criminal liability for delay in the delivery of detained persons to the proper judicial authorities, deliver said [charged or suspected]arrested person to the proper judicial authority within a period of thirty (30) days (security reform initiative proposes a maximum of fourteen (14) days.) Counted from the moment the said [charged or suspected] person has been [apprehended or] arrested excluding Saturday, Sunday and Holidays.[, detained, and taken into custody by the said police, or law enforcement personnel: provided, that the arrest of those suspected of the crime of terrorism or conspiracy to commit terrorism must result from the surveillance under sec. 7 and examination of bank deposits under sec. 27 of this act.]

Thirty days is too long and open to so many potential abuses of basic rights. As you know, Your Honors, journalists are victims of harassment suits and arbitrary arrests and detention for the flimsiest of reasons. On the inclusion of the cybercrime law as among the special laws that may be applied against suspected terrorists.

Your Honors, it was clear to the NUJP during the June 18, 2018 meeting that these bills were merely cobbled up versions of anti-terrorism laws by other countries such as Australia. This much the proponents admitted. What they dishonestly withhold from the TWG, however, is that the laws they copied have very clear definitions and exemptions as safeguards against abuse, something they did not bother to copy in their dangerous versions. Many provisions of House Bills 7141 and 5507 are bullets aimed to kill people’s civil, political and human rights.

And so, while the NUJP was encouraged by the Honorable Chairperson Rufino Biazon’s opening statement last June 18 that people’s rights must be guaranteed, we, however, declare our opposition to the bills.

Thank you.

NUJP National Directorate

Nonoy Espina Marlon Ramos Dabet Panelo

Chairperson Vice Chairperson Secretary General

Raymund Villanueva Jhoanna Ballaran Ron Lopez

Deputy Secretary General Treasurer Auditor

Directors

Nestor Burgos Gerg Cahiles Kath Cortez Virgilio Cuizon

Justine Dizon Sonny Fernandez Kimberlie Quitasol Richel Umel Judith Suarez