Marilao River polluters get away with small fines

The Clean Water Act of 2004 orders plants to pay discharge fees based on the volume of wastewater and pollutants that they release into water bodies. A self-monitoring mechanism in place allows polluters to report unreliable laboratory results, however.

BY ANNIE RUTH SABANGAN, ROBERT JA BASILIO JR., BERNARD TESTA AND RIC PUOD/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Part 3 of 4

Part 1: The Bulacan town where chickens are slaughtered and the river is dead

Part 2: ‘The wastewater looked like mud’: EMB goes after Vitarich Corp.

What you need to know about Part 3:

- Many pollutive business establishments, including chicken dressing plants releasing their wastewater into the Meycauayan-Marilao-Obando River System (MMORS), pay the government paltry wastewater discharge fees ranging from P5 to P500.

- From February 2016 to August 2018, the DENR collected only P1.4 million worth of wastewater discharge fees from these establishments for the rehabilitation of the MMORS, a drop in the ocean compared with the P11.5-billion fund needed to help revive the long-dead river system.

- Regulators have identified 49 mostly toxic substances dumped by polluters into the river system. But environment officers admit they’re unable to detect the presence of these pollutants in water bodies, let alone make erring establishments pay fines.

- The Environmental Management Bureau in Region 3 lacks the manpower to check the accuracy of the environmental self-monitoring reports (SMR) being submitted to it by business establishments in Central Luzon.

- A review of the SMRs submitted by seven poultry and meat processing and livestock establishments operating in Marilao, Bulacan showed that these had many glaring errors and inconsistencies — a proof of the bureau’s failure to vet the SMRs.

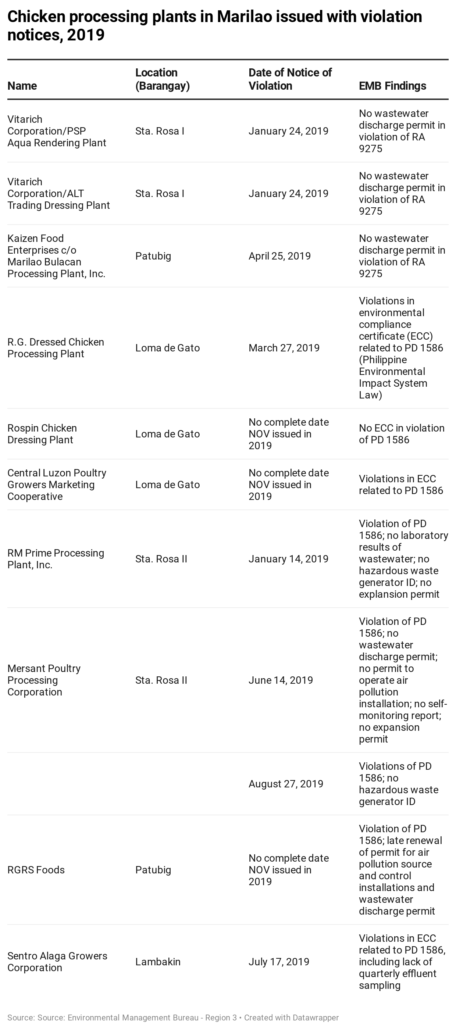

In 2019, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) issued violation notices to all but one of Marilao’s 11 chicken processing plants. They were punished not for polluting the Marilao River, however, but for technical violations related to their permits or failure to submit various reports.

Four plants in barangays Santa Rosa I, Santa Rosa II, and Patubig –– including two operating inside the compound of Vitarich Corporation –– had no wastewater discharge permits.

The other plants in Brgy. Loma De Gato either didn’t have Environmental Compliance Certificates (ECC), violated their ECCs, expanded operations without permits, were late in renewing permits, or failed to submit wastewater lab results.

This was how the regional environment office was able to get around its lack of capability to catch and punish which plants were responsible for polluting the Marilao River, part of a river system in Bulacan province that dumps wastes into the Manila Bay.

“Ang ginagawa ho namin is bina-violate namin sila sa mga permit nila. Tapos…pagka hindi pa rin po sila nakakapasa…sa mga permit nila na ‘yon, tuloy-tuloy po ‘yong violation…nila (What we do is charge them with violations through their permits. If they fail to secure permits, their violations continue),” said Glenn Aguilar, a staff member of the DENR’s Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) in Region 3.

Environmental regulators said it had been a challenge to get water samples. “’Yung possible na ma-sampling-an, doon lang kami nagsa-sampling (We only conduct sampling in establishments where it’s possible to get wastewater samples),”Aguilar said.

The chicken dressing plant of Vitarich Corp. was one of the few that EMB was able to inspect, and it was because its waste outfall was accessible, said Aguilar. “Sila (Vitarich) ang visible, talagang sila lang ang na-implicate (They’re the ones visible, thus they’re the only ones that got implicated),” he said.

Aguilar also accused the plants of making it hard for pollution inspectors to do their jobs. He said they would secretly turn off wastewater discharge when the inspectors arrived to inspect, preventing them from getting effluent samples in real time. It was also difficult for them to locate sewer pipes and waste outfalls especially inside residential compounds.

“Minsan hindi talaga umaamoy. Hindi sila nag-o-operate pagka napapadaan kami (They don’t smell [when inspectors go to check] because they make sure to shut down their operations when they know we are dropping by),” Aguilar said.

Lara Ibañez, Philippine country director of international non-profit environmental watchdog Pure Earth, said it’s not enough to punish polluters over permits and other technicalities.

She called for the strict enforcement of the 2004 Clean Water Act, passed by Congress to make sure that a thorough accounting of industrial wastewater pollutants and their toll on the environment is conducted regularly.

She said it’s important to be able to assess direct contributions of pollutive establishments and make them pay for the environmental and economic impacts of their discharges.

“We don’t see how much it (polluting water bodies) is really costing us,” Ibañez said in an interview in August 2019. She said the government should realize that implementing the Clean Water Act makes for sound economic policy because it will prevent environmental issues that have actually been costing the local government more.

Pure Earth is the new name of Blacksmith Institute, the watchdog that has put a spotlight on the pollution of the Meycauayan-Marilao-Obando River System (MMORS). In 2007, the watchdog named Marilao in its list of 30 “dirtiest” places on earth.

P5 to P500 wastewater discharge fees

The Clean Water Act imposes wastewater discharge fees, a fund intended to pay for the costs of government efforts to manage and clean up water bodies that absorb wastewater from industrial and commercial establishments.

However, Ibañez said the fee turned out to be “self-defeating” and the amounts that establishments had been paying did not reflect the true cost of the pollution that they had caused.

From February 2016 to August 2018, EMB Region 3 only collected P1.4 million of wastewater discharge fees from 388 establishments along the entire MMORS, based on documents that EMB Region 3’s senior environmental management specialist Ramjay Dizon showed to PCIJ.

It’s not commensurate with the P11.5 billion needed to rehabilitate the MMORS, based on experts’ estimates.

PCIJ’s analysis of the payments showed that almost half of them –– 167 establishments –– only paid between P5 and P500 in wastewater discharge fees. Only one establishment paid more than P50,000.

The wastewater discharge fees are computed based on the volume and the pollution levels of wastewater that plants release. Each establishment is made to pay P5 for every kilo of pollutants multiplied by its annual net biological oxygen demand (BOD) and total suspended fluids (TSS) waste loads in kilos, or the difference between waste load in the untreated water and the final effluent.

Ibañez said the formula is problematic. It only takes into account two out of 49 water quality parameters set by the EMB –– which include ammonia, boron, and chloride, arsenic, lead, and fecal coliform among others.

The wastewater discharge fee was intended to be a disincentive that would encourage the plants to modify their production practices and invest in pollution control technologies. The paltry fees accomplished the opposite, said Ibañez.

“Isipin mo, it’s even more profitable to just pay. I can just pollute and pay kasi mas affordable ‘yon, kaysa maglagay ako ng pollution control (Come to think of it, it’s even more profitable to just pay. I can just pollute and pay because that’s more affordable than putting up pollution control facilities),” she said.

In Marilao, four chicken dressing plants paid wastewater discharge fees during the time period.

Central Luzon Poultry Growers Marketing Cooperative in Brgy. Loma de Gato paid P7,540 in November 2016, P10,675 in March 2017, and P9,486 in March 2018.

Kaizen Food Enterprises, which operates under or with the Marilao Bulacan Processing Plant in Brgy. Patubig, paid P3,220 in July 2016. RG Dressed Chicken Processing Plant in Brgy. Loma de Gato shelled out P3,577 in the same month.

Vitarich Corp. and Alt Trading in Brgy. Sta Rosa I paid P39,715 in March 2017.

Self-monitoring reports

The problem is more than the formula, however. Computations for wastewater discharge fees are based on the plants’ declarations in Self-Monitoring Reports (SMRs) that they are required to submit quarterly under the law.

These SMRs have proven to be unreliable at best and manipulated at worst, according to regulators.

Wilma Uyaco, chief of the Clearance Permitting Division of the EMB’s National Capital Region (NCR) office, said the SMRs were intended to ease the burden of environmental regulators. “’Yung SMR, ‘yan ‘yung self-regulation na tinatawag. Kung ’yan ay magagampanan ng tama ng industries, e ’yun sana ang pinakamaganda kasi ang gobyerno hindi mahihirapan (That SMR is what is called self-regulation. It would be best if industries carried it out correctly so the government would no longer be burdened),” she said in an interview in October 2019.

However, enforcement has been far from effective, Uyaco said. “E kaso ‘yong self-regulation, hindi pa ready. Kino-comply pero tingin namin hindi 100% totoo (But they’re not ready yet in terms of self-regulation. It is being complied with but compliance is not 100% truthful).”

The EMB’s NCR office co-chairs the governing board of the MMORS Water Quality Management Area with EMB Region 3.

Enforced since 2004, the SMR system has two objectives under DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 2003-27: (1) allow establishments to demonstrate compliance with environmental laws; and (2) allow the EMB to confirm or validate that these firms comply with these laws.

Submitted every quarter, the SMRs are filled up by pollution control officers accredited by the DENR to report production capacities, actual outputs, number of operating hours in a day, number of workdays in a week, and quarterly water and electricity consumption.

It also reports the volume, types, and names of industry-specific wastes generated, emitted, or discharged, and how establishments dealt with the environmental impacts of their byproducts.

For poultry processing plants, this means disclosing the total number of chickens dressed, volume of water consumed per day and per quarter, chemical wastes generated from processing chicken, and how these wastes were stored, transported, treated or recycled, and disposed of.

The report also includes the cost of treating wastewater, investments made in the water treatment plant, the location of the facility’s wastewater discharge, and the water body where the wastewater was discharged.

Establishments must have their wastewater tested quarterly by a DENR-accredited third-party laboratory and report in their SMRs the concentrations of BOD, TSS, phosphate, acidity or pH, oil and grease, and nitrate, among others.

Wrong math, old lab tests, expired discharge permits

Uyaco said plants have cited unreliable lab tests in their SMRs, however, showing low oxygen demand in effluents to show that the treatment facilities of the establishments were effective in cleansing their wastewater.

“[S]ino ba naman ang maniniwala, septic tank lamang ang treatment facility nila pero ang result ng analysis na sina-submit sa SMR super mababa ’yung BOD?…Hindi ganoon katotoo ang result (Who would believe the results of the lab analysis in the SMR showing a very low BOD in wastewater, when an establishment’s treatment facility is just a septic tank? The results are not reliable),” she said.

About 50% of the submissions were inaccurate, said Mario Bangloy of the EMB-NCR’s Water and Air Quality Management Section in an interview with PCIJ in October 2019.

“(K)ung ‘yung sinasabi mo na hindi tama itong nire-report…medyo malayo sa (katotohanan), siguro kalahati (If you’re asking about incorrect reports… those that are a bit far from the truth, maybe it’s half),” said Bangloy.

The PCIJ requested Uyaco to review 2018 SMRs of seven poultry and meat processing and livestock establishments operating in Marilao. She found at least three glaring errors –– wrong math, old lab tests, and expired discharge permits.

She found discrepancies between per quarter declarations of total water consumption and the breakdown of water usage in six SMRs. Uyaco cited at least one chicken dressing facility declaring to have consumed a total of 25,000 cubic meters (m3) of water during the third quarter of 2018, but the sum of its reported daily consumption of domestic water, cooling water, and process water showed it consumed more. Its total water usage for one quarter was 28,440 m3 or 3,440 m3 more than what it declared.

“Saan nanggaling ang ibang tubig nila (Where did the rest of the water come from)?” Uyaco asked.

While Uyaco didn’t want to second-guess the reasons behind the discrepancy, she said the mathematical errors resulted in lower fees for the plants. “(B)ababa ‘yong masisingil sa kanilang bayarin, ‘yung wastewater charges… kasi hindi nare-report ng tama (Collections from their wastewater charges would decrease because it’s not being reported correctly),” she said.

Establishments have submitted old laboratory tests results, too. Uyaco spotted one chicken dressing establishment that used lab test results dated March 2018 for its SMR submitted for the third quarter.

“Mali na itong date ng (lab) analysis n’ya…Dapat hahanapan ‘yan o dapat hindi ‘yan tinanggap. Bakit ‘yan ang report mo? (The date of the lab analysis is already wrong…They should have asked for a new lab test result or they should not have accepted the SMR. They should have asked the establishment why its report was like that),” said Uyaco, irked by her discovery.

Like Vitarich Corp., many establishments were found to be using expired wastewater discharge permits.

The establishments are required to write on the first page of their SMRs the wastewater discharge permit reference numbers, date the permit was issued, and the date it will expire. One poultry processing facility used a 2016 permit for its third-quarter filing in 2018.

Of the seven Marilao-based poultry and meat processing and livestock establishments that Uyaco reviewed, six had expired wastewater discharge permits. Three had permits that expired as early as 2015 and 2016.

Clearly, Uyaco said, these establishments must not only be compelled to correct their SMRs but also be made answerable for their violations.

A “substantive evaluation” of the SMRs as mandated under DAO 2003-27 should have been done before the issuance of notices of deficiency against the erring establishments, she said.

If they were given time to address their deficiencies but were unable to solve the problem, the establishments should have been slapped with notices of violation, said Uyaco.

Poultry processors tampering with wastewater samples?

There are allegations that plants have been tampering with their wastewater samples.

“Kung ang treatment facility mo ay ganito tapos magsa-submit ng result ng analysis na ganoon kalinis, na ganoon kababa ang BOD, so makakapag-isip ka na something is wrong, or something has happened di ba? Ganoon ‘yun (So if your treatment facility is like this and then you submit results of water analysis as clean as that, with a very low BOD, then you make one think that something is wrong, or something has happened, isn’t it? It’s like that),” said Uyaco.

She said several cases have been reported to her by pollution inspectors.

“(M)ay nagsasabi rin sa amin pag nag-i-inspect na ganito raw ang ginagawa ng third-party laboratory, dinadagdagan na ng chemicals ‘yung container…kaya pagdating doon mababa ang result (There were those who told us that upon inspection they would find out that this was what third-party laboratories do, they put chemicals into the container…that’s why when it reaches the lab, the result is low),” the EMB official said.

“Dinadaya talaga kasi intentional ‘yung ganoon. Kaya ’yun kung may mga info silang nakukuha, inilalagay ko ’yan sa reports (It’s being tampered with because those things are intentional. That’s why when they get pieces of information like that, I include them in the reports),” she added, referring to reports she writes in relation to the evaluation of SMRs.

A DENR-accredited third-party laboratory housed at Ateneo de Manila University in Quezon City also confirmed the allegations. “It can [be tampered with]. That’s true,” Armando Guidote, director of the Philippine Institute of Pure and Applied Chemistry (Pipac), told the PCIJ in 2019.

Guidote, professor at the Ateneo’s Department of Chemistry, was quick to add that while tampering was possible, it did not necessarily mean that it was the result of collusion between a business establishment and a third-party lab, especially when the latter did not know where and how the wastewater samples were taken.

“Our analysis is based on the samples that they (establishments) bring,” Guidote said.

At the EMB office in Region 3, Elisa Dimaliwat, chief of the bureau’s Environmental Monitoring and Enforcement Division at the time of her interview with PCIJ in 2019, said she would rather trust in the capability of establishments to do honest-to-goodness self-monitoring with the assistance of accredited third-party testing firms.

She said the laboratories that analyzed the effluent samples of establishments went thorough screening by the DENR. “Naka-accredit ‘yan… kasi ang third-party lab hindi n’ya p’wedeng lokohin ‘yong resulta n’ya, masisira s’ya, ‘di ba po? (They’re accredited…Third-party labs can’t tamper with the results or they would ruin themselves, won’t they?)” Dimaliwat told the PCIJ.

It would also be hard for companies to fabricate information in their SMRs as they would risk being shut down, she said.

Bangloy said not all inaccuracies were a result of deliberate moves to fake SMRs and cover up pollution.

SMRs require 200 pieces of information spread over six modules, he said. Incompetent pollution control officers or PCOs my be responsible for the errors.

“The [SMR] is so technical. Saan ka makakakita ng engineer [na PCO] sa isang gasolinahan? Mga cashier lang, mga ganoon… (The SMR is so technical. Where can you find an engineer working as a PCO in a gasoline station? Usually, cashiers and the like act as PCOs in these kinds of establishments),” he said.

DENR guidelines require establishments classified as big generators of pollution to hire licensed engineers or chemists with at least two years of relevant experience in environmental management. Small generators of pollution may hire graduates of technical courses related to the job, or they must have reached at least third-year college.

The PCOs may also be a professional in the fields of engineering or physical and natural sciences, with at least three years of relevant experience in environmental management, or a different field but with at least five years of experience.

Too many reports, too few people, too little time

The EMB is supposed to exercise oversight of the self-monitoring process, validating their declarations and checking that they have complied with environmental requirements.

SMRs found to be incomplete are supposed to be returned to the companies, which would have 30 days to revise and correct their reports.

But the bureau rarely returned incorrect SMRs. “Hindi madalas (Not often),” said Dizon of the EMB Region 3’s Environmental Monitoring and Enforcement Division, when the PCIJ asked him in late 2019.

“Hindi nare-review lahat ng SMRs…Additional burden sa amin. Sa dami ng firms baka di namin kayanin (Not all SMRs can be reviewed…It’s an additional burden to us. We may not be able to review everything because there are so many firms),” added Vicente dela Cruz, chief of the division’s Chemicals and Hazardous Waste Management Section, in a phone interview in early 2019.

In 2018, a total of 3,816 business establishments from seven provinces submitted SMRs to the EMB office in Central Luzon, based on data culled by the PCIJ from the bureau’s Management Information System Unit.

If each establishment submitted four 16-page SMRs in a year, that meant that in 2018, a total of 15,264 SMRs consisting of 244,224 pages needed to be reviewed.

The Environmental Monitoring and Enforcement Division only had 15 staffers, according to Dizon. Each staffer would have needed to evaluate 1,018 reports — nearly 16,300 pages — if they were to review all of the reports.

What makes the work harder, said Dizon, is the limited time allowed under DAO 2003-27 — only 30 days — to act on problematic SMRs. The division also has other responsibilities.

After the 30-day period, the incorrect reports can no longer be reviewed and the deficiencies cited in the documents can no longer become the basis for the issuance of violation notices.

The establishments can then go scot-free. — PCIJ, February 2021

Next: PCIJ brings water samples from Marilao River to a laboratory for testing

This series was produced with the support of Greenpeace Southeast Asia-Philippines.— PCIJ