Electricity that does not destroy the environment

[SECOND OF TWO PARTS]

A special report by Raymund B. Villanueva

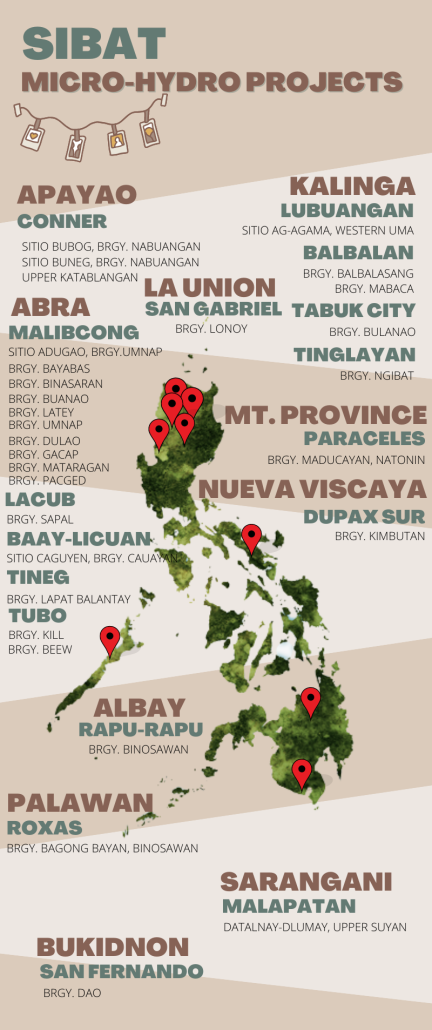

UPPER Katablangan in Conner, Apayao province enjoys 20 years of nearly uninterrupted power supply from the community’s micro-hydro project this year. This remote community located 20 kilometers from its nearest neighboring barangay could be reached with an eight-hour trek up a perilous foot trail when it is rainy or two hours on expertly-driven motorcycles when the road is dry enough. It is one of the first barangays in Abra, Kalinga and Apayao provinces to build a micro-hydro power plant for electricity, a vital service often taken for granted in lowland communities.

READ PART 1: From bodong to electricity (A remote Isneg community enjoys 2 decades of renewable energy)

Building a micro-hydro power project—it took the indigenous Isnegs of Katablangan six long years—is one thing, keeping it dependably running is another however. Maintaining a 7.5kw power plant where destructive typhoons often wreak havoc on lives and property, where replacement parts are hard to purchase and deliver, and where engineers of the Sibol ng Agham at Teknolohiya (SIBAT, their project partner) usually takes weeks to reach for repairs is hard. When these happen, these are the times that Katablangan reverts to dark nights, save for good old-fashioned kerosene lamps.

SIBAT engineer Jey Mart Erasquin said Katablangan was among their partner communities that followed their maintenance recommendations faithfully. “Their dam is cleaned regularly to prevent twigs and leaves from clogging the pipes that supply the water to the power station. If twigs and leaves keep going into the equipment, the blades may be damaged earlier. The station’s location close to the household also allows them to immediately shut the machines down if trouble arises,” Erasquin explained.

“We try our best to keep the equipment in good condition. The children do not like power outages while we watch our favorite television shows,” village elder Dalmacio “Dalma” Lugayan said laughingly.

The Katablangan mini-power station only had three breakdown and major equipment replacements in its two decades of operation. “Our equipment has an average lifespan of six or seven years,” Dalma explained, adding it usually takes weeks for replacement machines to arrive.

Each replacement part is usually of newer design and better quality, many of which engineers of SIBAT manufacture in their workshop in the organization’s organic farm in Capas, Tarlac. SIBAT engineers periodically return to install safety equipment such as lightning arresters and voltage regulators to keep power supply stable. Power belts and wiring have to be regularly replaced and upgraded as well. Last April, a bigger voltage regulator was installed at the power station that allows for a more stable 220 volt supply such as when power tools are used by the carpenters.

‘Change is difficult’

A large part of northern Cordillera remains among the Philippines’ off grid regions in terms of power connectivity from electric cooperatives. Government energy agencies are also still trying to ascertain specific numbers of households and communities that electricity distribution companies and cooperatives need to have connected to their power lines. Current estimates say 15 million Filipinos still do not have electricity in their homes.

“Electrification is a moving target of sorts because the census (done every five years) presents a bigger number of households that need to be connected to electricity providers,” Isak Jonathan Villanueva, National Electrification Administration (NEA) Renewable Energy Development Division principal engineer, said. He added that the country’s archipelagic nature presents a difficult challenge to put most of the Philippines on grid. “There are many areas that could not be easily connected to the Luzon or Visayas energy grids and have to generate their electricity from fossil fuel power plants. Consequently, interior communities are the last on the list in electricity connection projects,” Villanueva explained.

He added that the government is currently concentrating in Mindanao—such as in Misamis Occidental and Surigao Sur where there are newly-signed joint venture agreements between power distribution cooperatives and investors—in its effort to “energize” 75,150 households. It is one of the component projects under the Mindanao Development Authority and funded by multilateral groups such as the European Union, Villanueva said. He added that another renewable energy project is in the works in Pampanga province that uses solar power.

The expert said that the Department of Energy (DOE) is still in the process of identifying areas that need electrification in its drive to have the entire country connected to electricity distributors. Villanueva said he hopes the process gains momentum after the signing of the Microgrid Systems Law (Republic Act 11646) by former President Rodrigo Duterte last January 21. “The process of asking investors to submit bids for power generation and distribution in un-served and underserved areas follows,” Villanueva said. He revealed that the NEA has finished drafting the guidelines on the Microgrid Systems Act and its new Board under the Ferdinand Marcos Jr. administration is hoped to approve it anytime soon.

He added that among the incentives the newly-minted law offers is a value added tax holiday for the first seven years for renewable energy generators, “in addition to the fact that renewable energy redounds to lower electricity rates compared to coal that has a decreasing supply, particularly from Indonesia where we source a large quantity of it.”

Villanueva said power generation companies still lean towards “dirty fuel” such as coal. In addition, current standards only allow a maximum of 50 megawatts for renewable energy generators, another barrier to the achievement of 35 percent power generation from renewable sources by 2040 in accordance with Renewable Energy Law of 2008 (Republic Act 9513). The DOE reports that about 24 percent of the country’s power output is generated by renewable energy, mostly from hydroelectric dams.

“Change is difficult,” Villanueva admitted.

Nonetheless, the engineer said that independent and micro renewable energy initiatives such as micro hydropower, solar, wind and biomass power generators are slowly getting popular, albeit still regarded as less profitable for power-generators compared to those that use fossil fuels.

Off grid but renewable

Katablangan’s micro-hydro power project is seen as a small but viable alternative to the difficulties in supplying electricity to remote communities in regions such as in the Cordillera. In addition to micro-hydro projects, other communities in the area have hybrid power projects that combine their micro-hydro projects with solar panels and wind turbines offered by both the country’s tropical climate and the region’s elevated topography.

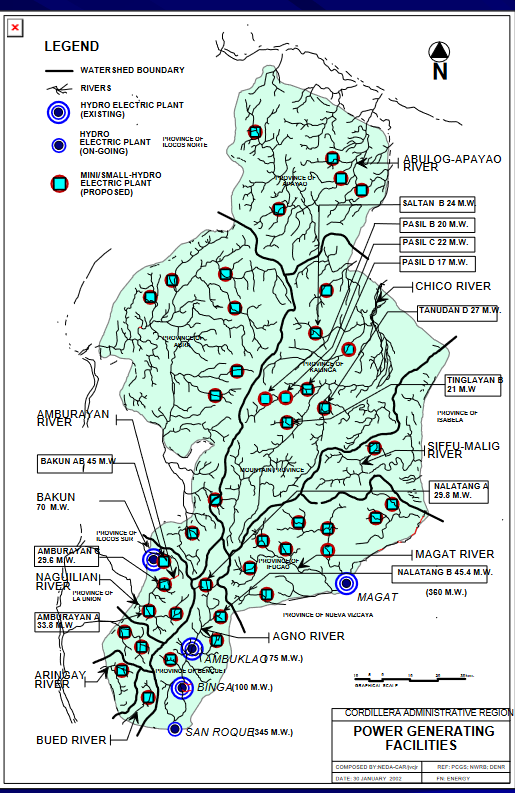

Church groups under the One Faith, One Nation, One Voice (OFONOV)-Cordillera Chapter support such projects it says makes judicious use of the environment as opposed to what it calls development aggression brought by the government’s insistence on constructing massive dams on the entire Chico River system and its major tributaries. OFONOV is made up of bishops, priests, nuns, ministers, missionaries, seminarians and members of the Roman Catholic Church as well as mainline Protestants under the National Council of the Philippines such as the United Church of Christ in the Philippines and Methodist Church of the Philippines. According to the OFONOV, there are five dams projects in Abra province, six in Apayao province (four of which are pending), and 11 in Kalinga province (two of which are pending). These are part of the 77 hydroelectric projects in the entire Cordillera Administrative Region, 66 of which have been completed.

The coalition however asks on whose benefit are the huge number of hydroelectric dams in the region’s many rivers. Electricity distribution cooperatives in the region, such as the controversial Benguet Electric Cooperative (Beneco), still buy a large portion of electricity they distribute from dirty fuel such as from the Sual coal-fired thermal power plant in Pangasinan province despite the fact that it has two of the country’s biggest hydro-electric dams in the country in the Ambuklao and Binga dams.

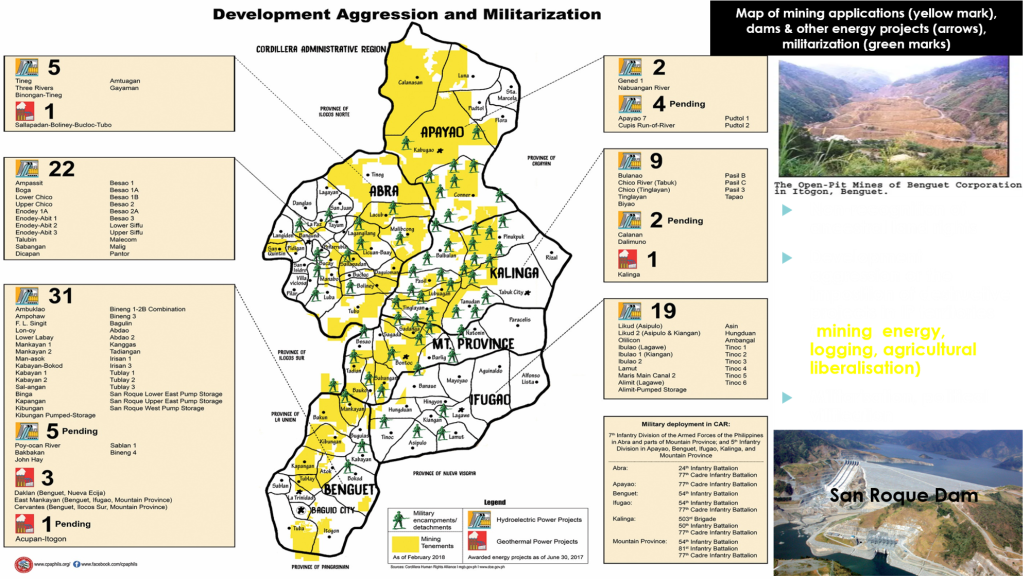

It is the Cordillera people’s opposition to hydropower dams that have reenergized their struggles for self determination since the Ferdinand Marcos Sr. dictatorship. Northern Cordillera’s successful opposition to the World Bank-funded first Chico River Dam project has created martyrs and heroes such as Macliing Dulag of the Butbut Tribe in Apayao and Petra Macliing of the Bontoc Tribe. The regional group Cordillera Peoples’ Alliance (CPA) is a product of the struggles and is still at it, often to their peril as shown by the abduction and torture of its Tabuk City-based officer Stephen Tauli last August 20. Tauli leads ongoing opposition to more dams in northern Cordillera. CPA said that such projects are accompanied by the deployment of more government troops in the area that inevitably lead to more human rights violations.

READ: Anti-dam activist’s abductors wanted him to turn gov’t spy

Cordillerans largely oppose more hydro-power dams they say often lead to floods, sedimentation and siltation that affect their farmlands, such as the case of the Gened 1 Hydroelectric Power Project (Gened 1 HEPP) they say would negatively impact seven upstream barangays of Kabugao town. “[W]hen sedimentations would be released and the spillway would be opened after torrential rains and typhoons, such would surely instigate downstream flooding that would certainly affect the downstream barangays in the municipalities of Pudtol, Flora, Sta. Marcela and Luna of the province of Apayao. And not only the five municipalities of Apayao but also the downstream four municipalities of the province of Cagayan, namely, Abulug, Pamplona, Ballesteros and Allacapan would also be tormented due to sedimentations and siltation from Gened 1 HEPP,” the OFONOV said in an April 2021 statement.

The coalition added that the project’s second phase, the Gened 2 Hydroelectric Power Project (Gened 2 HEPP) would similarly affect 12 more barangays with a combined population of 7,100 individuals according to the 2016 national census. Three more hydropower dams by the DOE are in pipeline in the towns of Calanasan and Conner, the Calanasan GenEd 2, Nabuangan dam and Cupis dam that are part of the $3 billion loan from the Chinese government by proponents Pan Pacific Renewable Power Philippines Corporation (PPRPC) as well as Strategic Power of San Miguel Corporation. Another dam project in Calanasan, the Apayao 7 MW project is being planned by Aboitiz Power.

The coalition added that 105 plant species, 51 bird species, 22 species of amphibians and reptiles, and 19 mammal species still abundant in Apayao are in danger from the hydropower projects.

“There is strong opposition of the Isnag indigenous people due to fact that their national minority rights to life, their ancestral lands and indigenous socio-political systems have been violated by acts of national oppression shown particularly in the non-compliance of the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) processes by the DoE, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples-Cordillera Administrative Region (NCIP-CAR) and the PPRPC management,” OFONOV said.

The group said it draws lessons from the sad experience of the Ibaloi tribe in Benguet province who were displaced by the Ambuklao and Binga dams in Benguet province and the San Roque Dam in nearby Pangasinan province. They said that the Isnegs strongly resist the construction of more dams in their ancestral domain as “these would totally dislocate and entirely separate them from their ancestral territories, rich resources and livelihood.”

“They do not want the dam projects as these would lead their communities to misery and suffering,” OFONOV said.

Two decades of renewable energy

Unlike the electricity projects of the government, foreign entities and corporations however, Katablangan’s micro-hydro power project has only enjoyed support and gratitude from its residents.

While Katablangan’s remoteness has deprived it of free broadcast television, all of its houses sport satellite dishes on their roofs that offer them more channels to watch. While no mobile phone service reaches the community, all of its households have several radio sets they use for such things as ordering items such as vinegar from the village stores or chatting with village mates. The power station also houses a rice and corn mill, liberating the residents from the backbreaking task and affording them more free time for other activities.

“Here in Conner, we have the unique phenomenon of lowlanders making the eight-hour trek up to our village to have their mobile phones, flashlights, radio sets, batteries and other gadgets recharged after strong typhoons have damaged their [on grid] power supply lines. Why is that? Because what we have here is a more reliable power supply that is cheaper and cleaner,” village chief Benito Lugayan said.

SIBAT executive director Estrella Catarata said that from the initial 42 households, the Katablangan micro-hydro electricity project has since expanded to Sitio Battong three kilometres away, increasing the number of serviced households to more than 60. They have also since revised their original billing of P50/month per household to P10 kwh in order to save funds for independent maintenance and upgrades. Catarata also reported that the new refrigerator and freezer at Katablangan’s stores are doing brisk business with new items such as ice, ice cream, ice candies, ice-cold soft drinks and frozen food items.

Because of Upper Katablangan’s success with its renewable energy project, people of Lower Katablangan have recently started digging for dams and canals for two micro-hydro power plants of its own. Catarata said that there are no guaranteed financial grants from foreign humanitarian organizations yet but the people have started digging for the dams and canals anyway.

“The Katablangan project is a story of the Cordillera’s abundant source of renewable energy that is harnessed by culturally-sensitive and appropriate technology for the benefit of its people. Its benefits only serve small and remote communities for now but there are many communities in need of electricity. The beauty in this is that it does no harm to the environment that the indigenous peoples still regard as sacred,” Catarata said. #

(This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.)

[This two-part special report is dedicated to the memory of Randy Felix P. Malayao—brave, true and loyal son of the North. This report’s final draft was finished on what would have been Randy’s 53rd birth anniversary last August 29.]