by Rosario Guzman

The transport chaos on the first day of the less restrictive general community quarantine (GCQ) was painful to watch. With limited public transport, thousands of Metro Manila commuters eager to recover lost jobs and incomes were practically left on their own to figure out how to get to work.

Department of Transportation (DOTr) secretary Arthur Tugade said that the government has “concrete plans” for GCQ. He also had to say that the government is not “sacrificing the people” just to revive the economy, because that was what it seemed.

The recommendation by the Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) to transition to GCQ was apparently based more on the compulsion to reopen business than on categorical facts of virus containment. The Duterte government was also reportedly already “out of funds” for socioeconomic relief.

The government once again resorted to the military. The military and police deployed trucks and cars to ferry the stranded passengers, breaking distancing protocol and betraying government’s lack of preparedness. Then, the usual victim blaming – the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) and Malacañang blamed commuters for the mayhem. Then, the DOTr made a U-turn from its initial pronouncement and said that it never promised to meet the transport needs of the public under GCQ.

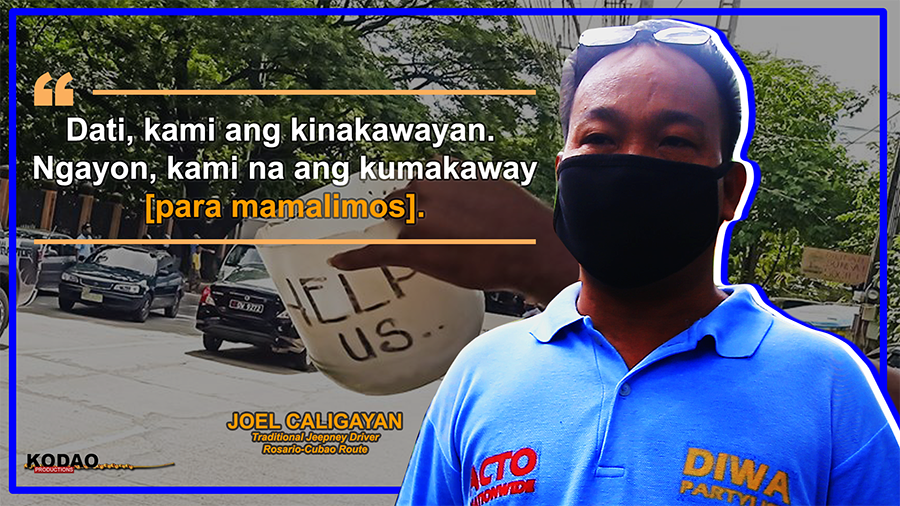

For the majority of poor commuters, what is more painful to see now is how the Duterte government, not backed by science, is on the verge of banning the traditional jeepney from the road forever and insisting that modernization is the cure.

If there is anything that COVID-19 has emphasized, it is the fact that the Philippine transport sector is in its worst crisis – a reality that the Duterte administration had repeatedly denied before the pandemic. If the economy has to transition to a genuinely better shape, the government has to address the basic woes of the transport sector. Vice versa, if the mass transport system has to be more efficient, the economy has to be transitioned to a genuinely better one.

But we seem to be stuck in our old problems.

Havoc in the new normal

The DOTr resumed public transport operations in two phases. During the first phase, trains and bus augmentation (which means bus loading and unloading at designated stations of MRT3), taxis, transport network vehicle services (TNVS), and point-to-point (P2P) buses were allowed with limits on the number of passengers. Tricycles were also allowed, subject to the approval of the concerned local government units (LGUs). Bicycles have also been encouraged.

During the second phase, public utility buses (PUB) and modern public utility vehicles or jeepneys (PUV/PUJ) were allowed with a limited number of passengers in rationalized routes. There are currently 30 routes from previously 96 routes for PUB and 34 new routes for the modern jeepneys. The DOTr will open more routes for the modern PUV in the coming days. Meanwhile, the traditional jeepneys remain prohibited from plying their routes unless seen as “roadworthy”. They are also the least priority and will only be used to fill in transportation gaps that arise.

Utility vans (UV) express will be allowed to operate with limited passengers as soon as more modern PUV routes are added. Provincial buses remain prohibited from entering Metro Manila.

The DOTr has also given some “new normal” guidelines, such as wearing of face masks at all times, cashless payments to avoid physical contact, use of thermal scanners, provision of alcohol and sanitizers, use of disinfection and establishment of disinfection facilities, and contact tracing. Costs for all of these are of course to be shouldered by the private transport operators and the passengers.

Apart from the added inconvenience these adjustments bring to the already unreliable mass transport system, there has also been lots of confusion on other relevant guidelines. The Philippine National Police (PNP) for instance prohibits backrides on motorcycles even for couples, yet some members of the police themselves are seen violating the rule. Interior and local government secretary Eduardo Año attempted to get around the prohibition by suggesting the use of sidecars but these are not allowed on the metro’s major highways.

Promoting the use of bicycles has not been accompanied by government policies to designate bike lanes and road-sharing with cyclists for a safe and efficient bike commute. Ironically, even the initiative by bikers’ groups and advocates to marshal the bike traffic along the “killer highway” Commonwealth Avenue was fined by the MMDA for “traffic obstruction”. Some LGUs are also reviving their old bike registration ordinances to collect fees even if they have not yet provided the needed support to bikers.

But the most glaring havoc is in the future of the traditional jeepneys – the ones that do not pass the DOTr’s standard of “modern” – which now hangs in the balance. Jeepneys were prohibited during the lockdown and are now under threat of being banned permanently from the roads in the name of the “new normal”.

The pandemic has obviously given the DOTr the opportunity to push for its “old normal” fixation on a modernization program that it has been proposing even before COVID-19. The modernization program revolves around: the digitization of fare and toll collection systems, vehicle registration, franchising, licensing, and navigation and positioning systems; routes rationalization; the transformation of EDSA; and jeepney phaseout.

It is premised on easing Metro Manila’s notorious traffic and pollution. But it is clearly a business-minded proposal that promotes the sales of private cars, modern PUVs and modern PUBs, and the privatization of transportation infrastructure. It is private transport-centric, while our obvious problem is the lack of an efficient and reliable public mass transport system. Now that the perennial road congestion is aggravated by physical distancing, the solution still seems to disfavor the mass of working class commuters.

Principles of E-R-A-S-E

The country badly needs an efficient, reliable, affordable, safe and environment-friendly public mass transport system. With or without the pandemic and physical distancing, these features of a public mass transport system should be ever-present for real and sustainable development. A strong government role is crucial in this.

Efficiency means that we are transported by vehicles through the shortest distance and in the shortest time possible. This also means less fuel use, less vehicle emissions, less costs, and less traffic.

Reliability means getting the mass of commuters to their destinations on time, with the least difference between the anticipated amount of travel time and the actual one. The crucial fact in reliability is that a large number of people rely on public transportation for their mobility.

Affordability and accessibility mean that the majority of the population who are wage workers and informal earners can afford public transportation and can easily avail of it from their dwelling and work places. This also includes facilities for persons with disability and senior citizens.

Safety includes measures that prevent harm to the riding public and create pedestrian-friendly conditions and infrastructure to reduce accidents and traffic deaths and to improve public health.

Finally, environment-friendly means public mass transport promotes healthier cities and living spaces. This includes the need to use clean and energy-efficient technologies and fuel for motorized transport on one hand, and the promotion of non-motorized modes such as walking and cycling on the other.

The crisis is real

The country’s public mass transport system is far from having these positive features. This reflects how the government has defaulted on its responsibility to ensure people’s mobility, and shows the general lack of national economic planning for sustainable development.

Our problem may be summarized as follows: 1) Mass transportation is left in the hands of private providers, including private rail corporations, bus franchises and single proprietors; 2) Deregulation is an operative principle in the entire sector, with the government’s role reduced to licensing, franchising and the like; 3) There is a lack of urban planning based on rural development and national industrialization that genuinely decongests the cities; and 4) Our mass transport system is corporate-driven, promoting the interests of infrastructure, transport, automobile and rail corporations as well as the profitability of real estate corporations, shopping malls, fare collecting banks, and the rest of the service-oriented and trading economy.

These problems manifest in many ways. The various modes of transportation are not fully linked, and there is heavy reliance on the ‘last-mile’ modes such as jeepneys, tricycles and even pedicabs. There is more road than rail transport, which is an indication of quite an unsustainable and expensive transport system. On the other hand, rail is privatized instead of being government-owned, controlled and operated, thus it is profit-driven and maintained by user-fees.

Fares are high as a consequence of privatized transport. According to the latest available data from the Family Income and Expenditure Survey in 2015, passenger transport for land travel eat up 7% of total non-food expenses of families in the National Capital Region (NCR). This covers fares for railway, jeepney, bus, taxi, tricycle and pedicab rides.

Transport is unreliable, with roads saturated and the quality of rail service poor. This is not to mention that roads are unsafe and rail accidents and breakdowns are frequent. Air pollution in the metropolis is one of the worst in the world, according to the World Health Organization. Lastly, there is a high volume of vehicles on the road. Navigation app Waze identified the Philippines as having “the worst traffic on earth”.

The anatomy of the transport mess

Metro Manila or the National Capital Region (NCR) has a total land area of 63,600 hectares and population of 12.9 million that swells to about 15 million by daytime. It accounts for one-third of the national economy and is home to about one-fourth of the urban population.

Metro Manila has six conferential roads and 10 radial roads. The radial roads do not intersect one another and intersect the conferential roads not more than twice. There are interchanges that separate these roads, but there are still missing sections in these interchanges. There are fully grade separated expressways in the north (NLEX), south (SLEX), and on the southwestern part (Cavitex) that connect Metro Manila to neighboring provinces.

These roads and highways were constructed to lead traffic in and out of the NCR. But lack of national economic planning has weakened job creation, increased rural poverty and displacement, and concentrated economic activities in the NCR. The region is the most congested city out of 278 cities in developing Asia, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The region is brimming with urban blight and poverty.

There are the more recently built Metro Manila Skyway and Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) Expressway to decongest SLEX and speed up travel to NAIA, the country’s major international gateway. These are also obviously to cope with the high traffic brought on by government’s labor export policy. The country’s international airports process the some 6,000 Filipino migrant workers who leave the country every day, which is more than twice as many as new jobs created locally.

There are more than three million registered motor vehicles in the NCR as of 2019, which accounts for almost one-fourth of the country’s total. This is a 9.7% increase from 2018 and a 28% increase from 2016, yet the urban space is finite and unchanging.

The latest data for vehicles disaggregated by type is as of 2016. It shows that motorcycles or tricycles comprised almost 40% of registered vehicles in NCR. Utility vehicles follow at 36% and cars and sports utility vehicles are at almost 30 percent.

On the other hand, the latest statistics on units for land transportation services is as of 2012, which shows that PUJs accounted for most of the franchises and units. There were 49,305 PUJ franchises and 50,153 PUJ units, which only shows that jeepney operators are small-scale and own only a little more than one unit. There were no registered PUBs in the NCR at that time, but there are 14,500 registered buses by 2016. If we try to extrapolate the 2012 data, considering that the number of PUJs almost remains the same over time, it means that PUJs and PUBs accounted for only 7.8% of registered utility vehicles in 2016.

The MMDA recorded an average daily volume of 405,882 vehicles plying the main thoroughfare EDSA in 2019, an increase of 22,054 vehicles from the previous year. About 63% of this volume are cars (255,732 units). PUBs make up only about 3% of total EDSA traffic, while PUJs are not allowed along EDSA. There is therefore no statistical basis to blame mainly the PUBs and PUJs for the traffic and transport anarchy in Metro Manila.

Traffic demand is at 12.8 million trips in Metro Manila, based on a study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Public transport accounts for 69% of total trips. The lesser share (31%) is done by private mode, and yet it is this mode that takes up 78% of road space. The traffic volume within the metropolis already exceeds the capacities of existing roads.

In terms of rail, Metro Manila has one commuter line (the Philippine National Railway or PNR) and three rapid rail lines (LRT1, LRT2 and MRT3). It has the least number of rail lines and the shortest urban rail system (51 kilometers) among 11 major Asian cities. The rail lines are not fully linked, only compounding the problem of an intermodal transport system where Metro Manila commuters use a variety of modes of transport and take an average of two to three transfers to reach their destinations.

MRT3 is privately owned like the PUBs, PUJs, taxis, TNVS, P2P, and UV express. The PNR, LRT1 and LRT2 are the only government transportation assets, although the operations and maintenance of LRT1 are privatized. The government does not subsidize fares, and in fact increases fares to attract private contractors.

The rapid rail system is the epitome of the inefficient, unreliable, unsafe and unsustainable public mass transport system in NCR. It is bogged down by frequent breakdowns, diminishing numbers of operational trains, accidents, inappropriate trains, and even non-working elevators and escalators. It is also in the center of corruption controversies.

Where does the commuter figure in all of this mess? The government through all its numerous transport agencies cannot even give a complete picture. An oft-cited study by JICA estimates that 39% of passengers’ trips in Metro Manila and nearby provinces are by jeepney and 38% are by tricycle. This indicates over-reliance on what has only been a coping mechanism for lack of system. Buses account for 13.6% and trains for only 8.6% of the number of trips by public mode.

Per day, LRT1 and MRT3 carry about half a million passengers each, while LRT2 ferries more than 200,000 passengers. Taking into account the number of registered buses and the estimated vehicle capacity by the JICA study, it may be surmised that buses also carry half a million passengers. Using the same extrapolation, jeepneys have the same passenger load.

Privatizing the rapid rail lines and phasing out the ever-reliable traditional jeepneys are therefore not solutions to the transport crisis. #

The last part of this series will discuss how government uses the pandemic to justify pre-COVID programs like the jeepney phaseout and Build, Build, Build that will further aggravate the socioeconomic crisis, and what steps government should take to genuinely address the country’s mass transport troubles.