Land grabbing endangers PH agri productivity–experts

FOOD security activists challenged the Rodrigo Duterte government to end land grabbing activities against farmers and indigenous peoples in a conference last August 1 at Balay Kalinaw, University of the Philippines-Diliman.

The Philippine Network of Security Food Programmes, Inc. (PNSFP) presented cases of land grabbing throughout the country, as well as their campaigns and mass actions.

Agricultural land in the Philippines decreased by 2.785 million hectares from 5.4 million from 2002 to 2012 due to land grabbing and the subsequent conversion of agricultural lands for other uses, such as mining and Special Economic Zones, PNSFP advocacy officer Sharlene Lopez said.

She added that the Philippines’ agricultural productivity, rural communities and environment are increasingly at risk if land grabbing continues.

According to PNFSP studies, many land grabbing victims were deceived by the promise of fortune into planting cash crops like rubber or oil palm.

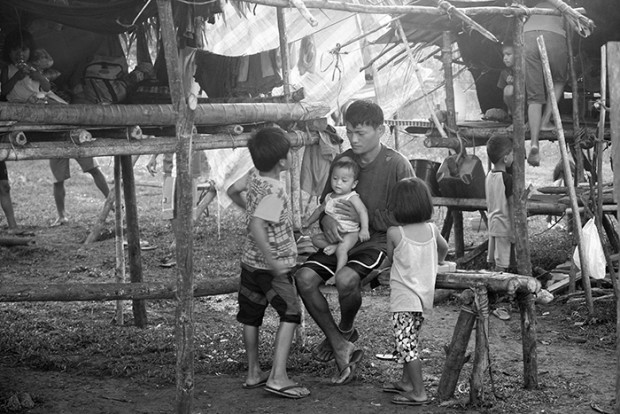

Others were forcibly displaced by militarization or “projects” by either the local government or big businesses.

Many also end up having no choice but to work at cash crop plantations for less than the minimum wage.

A panel of government reactors from the Office of the Cabinet Secretary, the National Anti-Poverty Commission transition team, the Office of the Secretary of Agrarian Reform, the House of Representatives (HOR) Committee on Food Security and HOR Committee on Agrarian Reform said their respective departments would try their best to return the farmlands and ancestral domains to the people.

Despite their assurances, however, Niklas Reese of the Philippine Bureau-Germany encouraged the participants to continue their advocacy against land grabbing.

“We have to be aware that the change of administration doesn’t change the nature of capitalism. We have to be vigilant; we have to be aware,” he said.

Reese added that the government should also to prosecute land grabbers.

“The role of social movements like this one is not just for demanding change, but accountability from the government as well,” Resse said. # (By Abril Layad B. Ayroso)