ANG ‘HULING EL BIMBO, THE MUSICAL’ REVIEW: When is nostalgia too much that it hurts?

By L.S. Mendizabal

Spoiler alert! Trigger warning: rape

The recent free streaming of Ang Huling El Bimbo The Musical on ABS-CBN’s Facebook page and YouTube channel was trending over the weekend and has since bred long, heated discussions among netizens on its content over form. Directed and choreographed by Dexter Santos, it delivered his signature masterful storytelling which I had had the privilege to be spellbound with in his earlier productions in Dulaang UP back in college. All the songs by the Eraserheads, about 30 in total, which provided the show’s repertoire, are hauntingly familiar to 90s kids and babies alike. As for the writing, I could not find fault in Dingdong Novenario when it came down to the accuracy of the times, human characterization, the right balance between humor and tragedy and the most difficult task of building a distinctly unforgettable story around already very iconic songs. “I hope I do the band justice,” Novenario once said in an interview. Frankly, this was where the problem lays. Now, before you come for me, let me just say that I enjoyed the musical thoroughly—it’s really hard not to love anything from Santos, anyway—except for a single scene which I personally found a bit too jarring and which I shall go over later as we try to examine both form and content.

Act One began in medias res with a police officer looking down at a dead body. This served as the catalyst for all the turmoil that would disturb the otherwise comfortable lives of three successful middle-aged men: Emman, a government employee, Anthony, a wealthy businessman and Hector, an established director. These men had history, being college roommates and best friends in the 90s. Their nostalgia kicked off with flashbacks to some of the oldest Eraserheads songs juxtaposed with their freshman life in a state university that looked and sounded a lot like the University of the Philippines. I especially loved the numerous song mashups, while the ROTC drill number was quite the spectacle and was easily one of my favorite parts of the musical, granted that watching this live must have been leaps and bounds better. The three boys would then meet Joy, a perky out-of-school merienda peddler about the same age as they were. She became an instant fascination for the boys because of the special attention given to her by their ROTC commandant, Banlaoi, played to evil caricature perfection by Jamie Wilson. Meanwhile, Joy was given life and dimension by Gab Pangilinan with her morena complexion, convincing tambay speak and powerful vocals. Her character in Act One was the epitome of “pure innocence with a dash of daring.” Like the three boys, she was always smiling and hoping, a persistent believer of true love and chaser of dreams. In contrast to the boys, however, she could not afford to hope and dream as big as they did. But they found common ground in youthful idealism and built an effectively portrayed, uncontrived friendship. This would soon be challenged by one night that changed their lives forever, Joy’s moreso, when they went on a road trip to Antipolo (“Overlooking!”) while, of course, singing “Overdrive” and “Alapaap.” These upbeat songs were followed by the slow acoustic, “Fill Her’, which menacingly ushered in the closing of the act with drunk male strangers raping Joy while the three boys were trapped in the car, held at gunpoint.

From happy nostalgia, Act Two opened just a day after that ill-fated night in an entirely different tone. Joy’s hair, which was previously in a half-crown braid now hung limply in a half-ponytail, her eyes empty, her smile not quite the same. She was about to attend the boys’ university graduation as one of the guests, but they forgot her. Together with the other graduates, the boys sang, “Lift your head, baby, don’t be scared / Of the things that could go wrong along the way / You’ll get by with a smile….” Oddly, this particular scene evoked the same “optimistic” mood in the Philippine Department of Tourism’s tribute video for our frontliners where shots of an empty metropolis alternated between images of doctors, nurses, the armed forces, etc. with a female rendition of “With a Smile” playing in the background. While the national president threatens to “shoot people dead,” we will survive this pandemic with a smile. While a girl was gang-raped, everything was going to be alright as long as we stayed positive. In the midst of trials and tribulations, there is always hope. Unfortunately, not for Joy. After the graduation rites, each of the boys acknowledged her presence, but not a word about the night before was uttered. This was to be the last time they would see her alive.

From the boys’ college experiences, the focus shifted from hereon to Joy’s struggle in the streets. Her Tiya Dely’s (who’d never be played better than by Sheila Francisco. Man, those pipes!) canteen was constantly being extorted by Banlaoi who happened to be their patron and “protector.” Unless they came up with a new gimmick, the eatery would go bankrupt and face imminent closure. Santos utilized the effect of the revolving stage here so that it wasn’t for the sole purpose of transitioning in and out of scenes but more importantly, for setting the mood and tone of every moment that defined Joy’s downward spiral. “Toyang’s Canteen” slowly turned into “Toyang’s KTV” where female waitresses, sex workers, male customers and drug pushers and users abound. From wearing a lot of yellow that accurately reflected her sunny disposition in Act One, Joy now wore different colors in cooler tones, her hair now loose and disheveled, her smile replaced with a fixed grim expression. Joy, as also symbolized by their eatery, had now completely lost her innocence.

Older Joy was played by Menchu Lauchengco-Yulo whom, in my humble opinion, I have seen in more note-worthy performances. It was easy to suspend disbelief on how physically different Yulo and Pangilinan looked, what with the former’s striking mestiza features, but her American enunciation of certain lines in Taglish and Filipino personally distracted me, considering that she was supposed to be from the urban poor. Nevertheless, it was apparent that the Joy we now saw was no longer the same person literally and figuratively. Naturally, an Eraserheads musical depicting rape would not be complete without singing “Spoliarium.” It was sung in staccato in the confrontation dialogues among the three boys as well as their grown selves (anyone else reminded of Tito, Vic and Joey?)—arguably the most powerful scene in the play. The perfect climax from a slow build of pent-up emotions of male guilt, fear and self-loathing because of what they failed to do for Joy then and how they now all deliberately avoided her when she needed them most. While they did lose their boyhood innocence along the way, it was not quite as tragic as in Joy’s case since her innocence was forcibly, violently taken away from her. Male middle-class nostalgia gave way to an intense clash of principles, justifications and differing, possibly repressed, memories in the heads of the lost boys. “Ewan mo at ewan natin / Sino’ng may pakana / At bakit ba tumilapon ang / Gintong alak diyan sa paligid mo?” Novenario’s writing shone brightest here.

The last 30 minutes, to me, was a pain to watch not because of Joy’s hit-and-run death—we already knew right from the beginning that this was not a tale with a happy ending—but because of the overwhelming romantic sentimentality surrounding it. The three men’s guilt came full circle when they met Joy’s daughter, Ligaya (played by The Voice Kids Philippines 2019 semi-finalist Alexa Salcedo), who casually recounted how her mother described each of them: the “bespren,” the “kuya,” the “pinakaminahal sa lahat.” How a scene could be both tear-jerking and cringe-inducing was certainly baffling to me. You know that these three men were full of bullshit, and yet you feel sympathy for them and pity for Ligaya and Tiya Dely. “Lahat tayo’y mabubuhay ng tahimik at buong ligaya.” Beautiful. Unsettling. Painful to watch. And somehow, I wish it ended right there.

Alas! There had to be a decent funeral for Joy, obviously, paid for by her more successful and fortunate friends. There had to be touching elegies and parting words from Ligaya and the three men preceding a big ol’ group hug to the lyrics of “Ang Huling El Bimbo.” “Magkahawak ang ating kamay / At walang kamalay-malay / Na tinuruan mo ang puso ko / Na umibig nang tunay.” Suddenly, a girl’s rape turned into three boys’ coming-of-age story that came to a closure just now as they were brought together again by her death. Joy who was not only raped, mind you, but was a victim of forced prostitution and drug trafficking, notwithstanding all her misfortunes which are innate to the social class she was born into, was able to teach these poor, miserable middle-aged men what love truly meant. Awwww. If nostalgia was a drug, this part would be the pinnacle of the high where intoxication breeds euphoria. And as in a hallucinatory sequence, the three college boys and a once more young Joy appeared onstage, climbing over the hood of the car atop a hill in Antipolo, while a ghost-like Ligaya joined them until they froze, all their arms raised towards the night sky as if to touch tomorrow. Was Ligaya the silver lining behind all the dark clouds that had crept into and cloaked over Joy’s life? For some reason, I was not quite sold on that metaphorical tableau. It was pretty to look at, sure, but it was too unnervingly romantic. If anything, Ligaya would only be another Joy once these men decided to backslide into their comfortable lives in social oblivion again, just as they did when they abandoned Joy many times over.

I would not go as far as calling Joy a “disposable woman” trope because her character was not flat like that, or the men’s arc as “redemptive,” although they tend to give those impressions on the surface level. The way I see it, the story was not about the three boys. It was always about Joy and how the system broke her through the men’s points of view. Because of this strong male perspective, Joy was narrowed into nothing more than a plot device that helped advance the men’s overall narrative and character development. There was an interesting symbolic analysis that I read on Twitter that said Joy represents the exploited poor, while Banlaoi embodies the exploiting, oppressive state. The government (Emman), the rich private sector (Anthony) and the media (Hector) can only do so much to alleviate the dire conditions of the poor because at the end of the day, they are still all instruments of the state. Ang Huling El Bimbo the Musical only intended to portray the harsh reality of being a Filipino, let alone being an impoverished Filipino woman. While legitimate, I still had problems with this appraisal based on the play’s form and content. To be honest, I found the musical to be leaning towards Idealism more than Realism because of the heavily romanticized rendering of forgiveness and absolution for the three men in the last few scenes. It was obviously teetering between some kind of resolution and resilience porn. “But that’s what rape victims are inclined to do in the end: they forgive,” some might argue, and carelessly and unfairly so. You’d be surprised to find out how many Joy’s you might actually know in real life and how many Emman’s, Anthony’s and Hector’s who allowed rape to happen and continue to tolerate it by keeping quiet. After all, isn’t rape the only crime in which it is the victim who must prove her innocence? Not all victims are able to forgive their rapists, and for this reason alone, my heart bleeds for all the Joy’s I know.

“But it’s not supposed to be revolutionary or progressive in the least,” some have said. Look, I know. Eraserheads are no The Jerks or Yano. Even the slightest indication of student activism in Emman’s line about being frustrated with the masses because they couldn’t understand the language of student activists (hence the need for “education among the masses” instead of the other way around) was a dead giveaway that this was no socially progressive play. The main protagonists, not excluding the adorable probinsyano, Emman, did not hail from the grassroots. And yet, in order for art to actually mean something, it has to mirror the times and in mirroring the times, social critique is inevitable. Otherwise, we would consider Brillante Mendoza’s poverty porn “supreme art” rather than what they simply are. This watered down social angling, to me, was the musical’s weakness. By choosing to be more romantic and idealistic in tone towards the end, perhaps to please the upper middle class audience for which it was originally produced and staged, the social commentary got lost, drowned by waves and waves of nostalgia. And you know what happens when historical nostalgia is delivered in high doses? It revises history itself. That is why by the end of the show, the men would earn the audience’s sympathy more than ire.

By making this theatrical production watchable for the larger part of the middle classes on the internet, it has opened a new, active discourse on theatre as a political venue in espousing progressive beliefs that should benefit the masses, not alienate them. It has also successfully given new life to appreciating theatre as an art form, the importance of its accessibility to the masses and the justness of fair and equal pay for all genders in theatre (did you know that female actors are sometimes paid less than their male counterparts?) for their hard work. And we live for these kinds of discourses. And yet, is it right to point some weaknesses out in the musical’s narrative and artistic expressions used? I believe so. Is it only right to challenge our artists and writers to come up with a musical, a story, that Filipino women, especially rape victims, deserve? Absolutely.

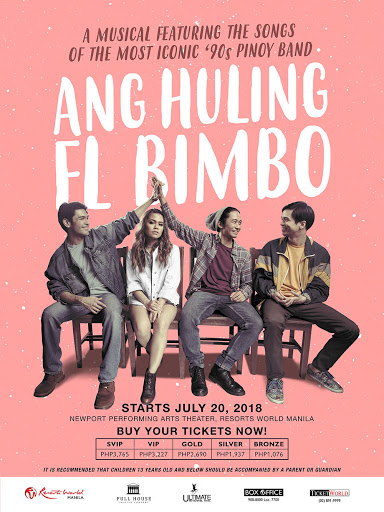

Not wanting to be an infinite wellspring of negativity, I watched the musical all the way through the credits. I was waiting for some sort of condemnation of rape and other forms of sexual abuse. None. But, hey, let’s look at the bright side: thunderous applause filled the whole of Newport Performing Arts Theater at Resorts World Manila when they called Eraserheads frontman, Ely Buendia, to join the cast of actors and production crew onstage. Indeed, Ang Huling El Bimbo the Musical was able to achieve its goal, which was simply to do the most iconic Filipino band in the 90s justice. #